|

Trades and

Industries, up to the end of the 17th Century

It was inevitable that metalworking in one form

or another would be carried out in the area, because of the plentiful

supplies of coal, iron ore, and limestone. Work at this time was

carried out in little workshops, often in a yard behind the

craftsman’s house. In the 15th century the churchwardens accounts at

All Saints’ Church list the local trades and industries in three

categories:

1. Smiths, braziers,

carriers, lime burners.

2. Millers, shearmen,

tailors, mercers, drapers, glovers, sempsters, and

barbers.

3. Cobblers, bakers,

butchers, and carpenters. |

Mining

Much of Walsall lies in the South Staffordshire

and Cannock Chase coalfields, often outcropping close to the

surface. By the early 14th century, coal and iron ore was being

mined. The lords of the manor (then divided), Roger de Morteyn, and

Margery Ruffus made an agreement to share the profits of the coal

and ironstone mines in the manor. Margery’s son, Sir Thomas le Rous

reserved the right to license coal-mining on land at Birchills in

1326 and 1327. By the late 1380s, and 1390s, there were coal and

ironstone mines in Windmill field.

Coal was mined in the manorial park, because

the manorial accounts for 1490 to 1491 include a payment for

prospecting for a mine there. By the middle of the 16th century, the

town was supplying coal to Sutton Coldfield. A document from the Calendar of Deeds, dated

1597 records a sale by William Webb, Mayor of Walsall, and others,

of land in Bloxwich to George Whitehall. The document states that

the purchaser promises to serve all the inhabitants of Walsall with

coals, called “dassell coalles” at the rate of three pence

for each horse, mare, or gelding load, and with others called “bagge

coalles” at two pence per like load, and to refuse none so long

as there be any coals upon the bank.

Large quantities of iron ore, or ironstone as

it is known, were to be found alongside the coal seams. The ore

often outcropped near the surface, particularly in the south, and

south eastern parts of the town. As already mentioned, the ore was

mined in the town in the early 14th century, and in Windmill field

by the late 1380s. In 1537 Thomas Acton was leasing mines in the

‘Foreign’, from the Crown, and by the early 17th century the ore was

supplied to ironworks in the surrounding area, including (from 1561)

Lord Paget's blast furnace on Cannock Chase. His son Henry leased 8

open cast mines in Walsall in 1576, and soon many more were to be

found in the area.

The carboniferous coal and iron measures lie

above a layer of Silurian limestone, which in places outcrops near

the surface, and so is relatively simple to mine. It is first

mentioned in a document dated 1325 which states that Sir Thomas le

Rous grants Robert Bonde three acres of his waste land in Birchills,

on condition that he should not make any mines of limestone in the

same. |

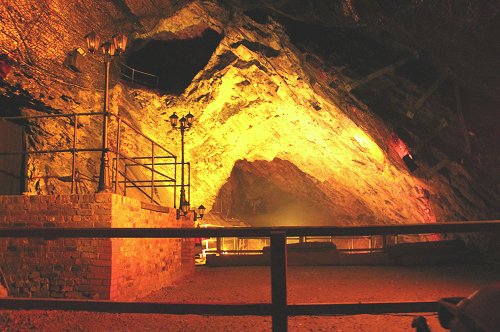

One of the limestone caverns

off the Dudley canal tunnel. It gives an impression

of the size of the caverns, and the vast amount of

limestone removed. |

It was mined in many areas around the town, from

the eastern edges, to Rushall, and in the town

centre itself, where the Arboretum now stands.

There were also mines at Townend Bank, and around

Church Hill, where the more valuable Upper and Lower

Wenlock Limestones are to be found.

The part of Church Hill around Ablewell Street

became known as Lime Pit Bank, as a result of the

extensive caverns that were dug under the hill. |

|

Much of the limestone was used

as building material, although it was also burnt to

produce lime, and used in agriculture as a

fertiliser. It became an essential ingredient for

tanners who soaked leather in a solution of lime to

remove any hairs. There is a list of trades in the

Staffordshire Record Office dating from around 1494

which includes a mention of lime burners in Walsall.

Cartloads of local limestone

were transported throughout the area. It became a

popular building material. Wenlock limestone was

favoured by ironmasters for use as a flux in the

smelting process. By 1569 it was being transported

to the ironworks at Middleton in Warwickshire. The

limestone on the eastern side of the town was known

as Barr Limestone, and mainly mined around Hay Head.

Much of the limestone at

Rushall was extracted from around 200 feet below

the surface. It was highly prized because when

polished it looked like marble.

Walsall Wood Colliery. From an

old postcard.

Metal Working

Although iron ore was plentiful

in the area, it seems likely that little smelting

was done in the town until the 14th century. By the

16th century several bloomeries producing iron were

operating in the town.

Around 1300 the lord of the

manor, Sir Roger de Morteyn granted Adam the bloomer

an acre of waste at Bloxwich, presumably on which to

set up a bloomery. It may be that iron was being

smelted in the Birchfields area in 1333, because by

that time the name Cinder Hill Field had appeared. |

|

In the late 14th century the

lord of the manor sold iron ore, and purchased the

finished metal from Robert Grubbere, an iron smith

working in his local bloomery. In 1528 an area near

the River Tame called Bloomsmithy meadow was sold to

Martin Pemerton, which suggests that a bloomery was

there before that date, presumably water-powered.

In the late 1570s, trees were

felled in Bentley to provide timber for charcoal

making. The trees were cut down by William Gorwey,

John Stone, and Richard Worthington to provide

charcoal for their ‘smithmills’.

There would have been many

smiths in the area who would have produced all the

different kinds of metal items that were in everyday

use, from household utensils and fittings, to tools,

agricultural implements, horseshoes, and weapons. In

1362 Robert Grubbere had a forge in the town, as did

Richard Marchal who made nails at his forge on

Church Hill. William Marshall had a forge in Rushall

Street, and William Mercer ran a forge in Bloxwich.

By the end of the 17th century

the many goods manufactured in the town included

awl-blades, buckles, chains, locks, nails, brass and

pewter holloware. |

An impression of an early

bloomery. |

|

Nails were made in Walsall by the late 14th

century. There were three nail makers in the town in 1603, and

several in Bloxwich. By the end of the century there were many more.

Locks were made in small numbers from the 16th century, and awl

blades were made in Bloxwich. They were used for boring holes in

wood and leather.

Horse Furniture

Walsall has been well known for a long time as

a centre for the production of horse-riding products such as

bridles, spurs, and stirrups etc. The industry had begun by the

start of the 15th century. The Burgess Roll includes the name of

John Sporior, listed as a spur maker. By 1435 Walsall had three makers of lorinery,

consisting of saddler’s ironmongery, bits, spurs, and other metal

objects.

Around 1540 the well known antiquary John

Leland visited the town. He had been authorised to examine, and use

the libraries of all religious houses in England by the king. He

compiled numerous lists of significant or unusual books, and

recorded evidence relating to the history of England and Wales. His

description of Walsall is as follows:

Walleshaul, a little market towne in

Stafordshir, a mile by north from Weddesbyrie. Ther be many smithes

and bytte makers yn the towne. It longgith now to the King, and

there is a parke of that name scant half a mile from the towne, yn

the way to Wolverhampton. At Walleshaul be pyttes of se cole, pyttes

of lyme, that serve also South Town (Sutton Coldfield) 4 miles off.

The William Salt Library has another

contemporary description of the town, possibly written by William

Wyrley towards the end of the 16th century:

Walsale is a fayre village, and although it

inivyneth (enjoys) a maior and priviledges, yet it hath no market,

but in it be good store of lorrimers, making bridle bitts, spurs,

and such like. This town was sometime belonging to the familie of

Hyllarie, but nowe doth acknowledge for lord Th. Wilbrome, of

Woodhey, in co. Chester, Esquier; near unto this is the head of

Thame, and in the church be these armes.

The description is followed by a series of drawings, made in the

church.

Horse furniture was being produced in Bloxwich

by the 16th century. In 1561, John Baily, a lorimer of Bloxwich,

died, and by the turn of the century there were at least two

others.

Locally made horse furniture was sold far and

wide. In 1542 Richard Hopkes of Walsall was owed money for stirrups,

'odd bits', fine bits, and snaffles, sold at Exeter, and Bristol, and

in Devonshire, Somerset, Dorset, and the West Riding of Yorkshire.

He was probably a dealer rather than a manufacturer, and also sold

locally made buckles. Another Walsall dealer, Nicholas Jackson died

in 1560. Half of his possessions consisted of bits, stirrups, spurs,

and buckles.

By the late 17th century shoe and garter

buckles were made locally, but most buckles were produced for

saddles.

In the 14th century, pewter and brassware

products were made in the town. There were many pewterers and

braziers making household utensils such as bottles, candlesticks,

chamber pots, dishes, kettles, pots and pans, plates, salt-cellars,

saucers, spoons, and warming-pans. There were also bell-founders,

and brass foundries casting window casements. Copper was also worked

in the town by the late 16th century. Copper smiths produced a wide

range of products including holloware, nails, and studs.

Leather

Walsall has become well known for its leather

goods, and saddles. By the middle of the 15th century there were

tanneries in the town, by the stream at Digbeth, and in Caldmore.

Finished leather goods were not produced until the 16th century, and

only in small quantities.

Weaving

By 1300 there was a fulling mill in the town,

and by the middle of the 15th century cloth was being produced.

William Staunton was a clothier who made an agreement with the

corporation in 1620 to teach 20 or 30 children the art of 'spinning,

twisting, doubling, and quilling' worsted, woollen, and linen yarn. |

|

When Dr. Robert Plot

visited Walsall in 1680 he described the

local industries as follows:

Nor are they less

curious in their ironworks at the town of

Walsall, which chiefly relate to somewhat of

horsemanship, such as spurs, bridles,

stirrups etc.” He mentions that the natives

were then skilled in the making of every

article connected with saddlery, and of all

kinds of buckles. Walsall men were familiar

with the arts of tinning metals, and the

casting of iron, copper, and brass pots.

Ironstone was raised at

this time, both at Walsall and at Rushall,

opposite the church, and was divided into

six different varieties:

|

1. |

Black Bothum |

|

2. |

Gray Bothum |

|

3. |

Chatterpye, being the colour

of a magpie |

|

4. |

Gray measure |

|

5. |

Mush |

|

6. |

White measure |

The two first are

seldom made use of, they are so very mean;

the two middle sorts but indifferent; the

two last, the principal sorts, but Mush the

best of all, a small comby-stone, othersome

round and hollow, and many times filled with

a briske sweet liquor, which the workmen

drink greedily, so very rich an ore that

they say it may be made into iron in a

common forge.

I think that the sweet

liquor that attends some of the iron ore,

deserves a little further consideration,

whereof I received a most accurate account

from the Worshipful Henry Leigh, of Rushall,

Esq., in whose lands, particularly in the

Mill Meadow, near the furnace in the Park;

in the Moss Close, near the old Vicarage

house; and in the furnace piece or Lesow, it

is frequently met with amongst the best sort

of Ironstone called Mush, in round or oval,

blackish and redish stones, sometimes as big

as the crown of ones hat, hollow and like a

honeycomb within, and holding a pint of this

matter, of a sweet sharp taste, very cold

and cutting, yet greedily drank by the

workmen.

After many enquiries

from old miners in the district, I have been

unable to find out anything definite

respecting this liquor. The ironstone is now

practically extinct, but traces of its

former existence are still to be found. The

ore from Rushall and Walsall - which latter,

however, was not quite so good, was used for

making tough iron, out of which the best

wares were made.

Limestone was dug all

about Walsall, particularly in the lands of

the learned Henry Leigh, Esq., where it lies

in beds for the most part horizontally. The

lime burners here were much more adroit than

those of other neighbourhoods.

The Ladypool Furnace at

Rushall supplied some excellent tough iron,

but softer iron, tin, copper, brass, lead,

resin and sal-ammoniac had to be imported

into the locality. |

|

|

During the next two hundred years, Walsall would grow into an

affluent manufacturing town, greatly helped by the canal, and

improvements to the roads, and transport. The industries so far

mentioned were small businesses, employing relatively few people,

but that would all change with the coming of factories, and mass

production. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to 16th, 17th centuries |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to The 18th Century |

|