|

At the beginning of the 18th

century the population of Walsall was just over 5,500,

almost twice what it was 100 years earlier.

In January 1701 Walsall Corporation

acquired the old manorial corn mill by The Bridge, from

the lady of the manor, Dame Elizabeth Wilbraham, on a

500 year lease, at an annual rent of two shillings. The

building was in a poor condition and the Corporation

agreed to repair it and to give any profits from

grinding to the poor. Repairs were made, and small sums

of money earned, but by 1763 the building had been

demolished or converted to other uses.

Difficult times for the

Corporation

During 18th century the

Corporation faced many problems. Its popularity was

at an all time low, there were difficulties in

recruiting members, financial crises, and

hostilities between the Borough and the Foreign.

Many of the burgesses were

tradesmen, who were not prepared to be members of

the Corporation, in case they had to make unpopular

decisions that might prejudice their business

interests. Foreigners, Nonconformists, Catholics,

and High Tories were excluded from the Corporation,

and until 1741 the Mayor received no payment for his

duties. After 1741 any mayor who served for two

consecutive years would receive a payment of £15,

from then on most mayors served a double period.

Corporation membership was lower

than ever, with rarely more than 12 members.

In the twenty years up until 1708, thirty Capital

Burgesses had been appointed to the Corporation, but

in the next twenty years only eleven were willing to

serve on the Corporation.

There were financial

difficulties, particularly over the poor rate.

People in the Borough were paying three times more

than those living in the Foreign, which led to

resentment, and the call for a general rate for

everyone in the town. In 1752, in an attempt to

overcome the problem, the magistrates appointed four

overseers for the whole town, in the hope that his

would lead to the establishment of a general rate.

Previously there had been separate overseers for the

Borough and the Foreign.

Walsall in about 1796. Stebbing Shaw.

The people in the Foreign would

have none of this, and one of the Foreign overseers,

Samuel Wilkes of Bloxwich went to prison rather than

handing his books over to the magistrates. The

leading inhabitants of Bloxwich took their case to

the Court of the King’s Bench on two occasions, each

time achieving a judgement against the magistrates.

In 1756 the magistrates finally gave-in and

reinstated the old system.

One of the Corporations’ most

serious problems was maintaining law and order.

There were a many disturbances by large disorganised

crowds, demonstrating against political parties, the

established church, Methodism, the crown, or more

usually high food prices. During one riot in 1750 an

effigy of King George II was hung on Church Hill.

In the latter half of the 18th

century many people were unemployed and could not afford

to properly feed themselves and their families. The

price of wheat had escalated, and so people took to the

streets, attacked millers, food wholesalers, and even

market traders. They believed that they could force

traders to reduce prices by rioting. Things were so bad

that in 1776 over twenty people were sworn-in as

constables to protect the market traders from rioting crowds, who

frequently attacked them, and were dissuading them

from coming to the market.

In 1780 a hundred coal miners

invaded the corn mill at Bescot, and forced the

miller to sell them wheat at five shillings a

bushel. They then marched to Walsall market and

forced the traders to do likewise.

The system of law and order was

inadequate to cope with the problem, which was made

worse by the rising population. The magistrates held

a petty session each week, and a Court of Quarter

Sessions. The town gaol was insecure and many

prisoners escaped, some being sent to Wolverhampton

for tighter security.

Relief for the poor

In 1723 poor relief legislation

was passed under the terms of the Workhouse Test Act

which stated that anyone wanting to receive poor

relief had to enter a workhouse and undertake a set

amount of work. The legislation was intended to

prevent irresponsible claims on a parish's poor

rate. By 1750 there were 600 parish workhouses in

England and Wales.

In 1717 Walsall Corporation

purchased three cottages on Church Hill, near the

church, from Mr. Thomas Harris of Worcester. By 1732

the cottages had been converted into Walsall’s first

workhouse, with accommodation for 130 people. The

first governor, Simon Cox was followed by Richard

Lambert, appointed in 1781 at a salary of £25. He

was given the following instructions, which were

recorded in the vestry book:

| That the said Richard

Lambert keep good order and rule

in the said house; that he and

the whole family go to rest and

rise at necessary and reasonable

hours; that the said house and

premises at all times be kept

clean, sweet and decent; also to

cause the seats and pews in the

said parish church to be swept

and cleaned every Saturday by

the poor in the said house,

without any expense to the

inhabitants; also that the said

governor of the said house, not

to have any private or weekly

bill for the use of the said

house or the poor, etc.;

likewise that he keep the poor

in the said house to work (such

as are not capable to go to

out-work) in such employment as

he shall think necessary and

most convenient. And those

out-workers, such as mechanics,

labourers, etc., the said master

to agree with all masters or

mistresses for such servants by

the day, the week, or piece, and

he to keep a memorandum book for

that purpose, by which means it

may be made known to the acting

overseer for the time being,

what is due from each master to

each servant, and the said

governor to collect such money

weekly, and transmit the same to

the overseer of the poor; also

the said governor to go on all

journeys on parish business or

such as are thought advisable by

the overseer or his colleague;

the said governor to pay the

poor, occasionally to assist the

overseer in buying of meat,

clothing, or other reasonable

business; the said governor to

be allowed all reasonable

charges upon journeys. It is

further agreed the said governor

shall not be allowed any other

perquisites, more than his

yearly wages of £25. |

|

In 1799 the workhouse was

enlarged to accommodate over 200 people. It had a

large dining room, 42 feet long by 15 feet wide,

with two very pleasant and airy lodging rooms above,

and a large workroom with facilities for spinning

wool and linen. The poor were expected to work there

and make their own clothes. The building was

inconveniently situated, being on top of the hill.

Water for drinking and washing had to be carried

there by hand. There was also a workhouse at

Bloxwich capable of holding around 100 people. Most

of the poor were given outdoor relief, and lived

away from the workhouse. They received payments for

rent, fuel, clothing, and medical expenses. In 1742

the expenditure for the poor amounted to

£338.17s.2½d. By 1810 this had increased to around

£2,000.

Many people insured themselves

against unemployment and sickness by joining clubs

and benefit societies. By the end of the century

there were 20 of them in the town, more than

anywhere else in Staffordshire. They had around

1,800 members, who in times of need received between

6 and 8 shillings a week, plus medical treatment.

A Municipal Cemetery and a

Racecourse

By 1750 there was almost no

space left in St. Matthew’s graveyard for burials

and so the Corporation purchased land off Bath

Street known as Windmill Field, and built what was

called the Old Burial Ground, Walsall’s first

municipal cemetery. It was surrounded by a brick

wall, the first bricks being laid at a ceremony in

March 1751 by Mr. A. Bealey, Mrs. Elizabeth Cox, and

the Rev. Robert Felton.

Walsall racecourse and grandstand. From Thomas

Pearce's History and Directory of Walsall.

Long Meadow in between Walsall

Brook and the mill stream was the site of the town’s

racecourse which opened in 1777. Meetings were held

annually during the Michaelmas Fair, and a

grandstand was added in 1809.

Trades in 1767

Sketchley’s Directory published

in 1767 contains the first detailed list of Walsall

trades. It listed 84 buckle makers, 66 chape makers,

38 publicans, 19 spur and rowel makers, 13 snaffle

makers, 10 ironmongers, 8 stirrup makers, 7 chapmen

and merchants, and several awl-blade makers,

blacksmiths, chandlers, curriers, fellmongers,

gunsmiths, locksmiths, nailers, skinners, tanners,

and whitesmiths.

Inns and Hostelries

In 1774 the owner of the New

Inn on the left-hand side of Park Street (looking

towards Town End) was looking for a new tenant. The

pub was described in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on

the 19th of September, 1774 as follows:

| To be let and entered

upon at Christmas next, all

that new erected and compleat

inn in Walsall, in the

County of Stafford, called

the New Inn, standing near

The Bridge and New Road, and

conveniently situated for

the reception of noblemen

and gentlemen travelling

through Walsall. The

business of the said inn is

daily increasing on account

of the turnpike roads being

made exceeding good from

Walsall to Birmingham,

Wolverhampton, Lichfield,

and Castle Bromwich, and

also from Walsall to a place

called Church Bridge upon

the Chester Road. The reason

Mr. Hart, the present

occupier leaves the said inn

is on account of his having

taken the Swan Inn in

Birmingham to which place

Mr. Hart goes on Christmas

next. The New Inn is

genteelly fitted up and the

bedding and furniture are

mostly new and very good,

which with the chaises and

horses will be sold to any

person inclined to take the

inn at a fair appraisement,

and great encouragement will

be given to a good tenant. |

|

Behind the inn was a well known

cock pit used for the sport of cock fighting. The

sport was very popular during the 18th century,

especially during race meetings. Higher up Park

Street, on the other side was Hancox and Clibury’s

Bell Foundry at Pott House. In 1634 they cast the

great bell for St. Mary’s Church in Lichfield. By

the latter half of the 18th century, Park Street had

become one of the most important streets in the

town, which resulted in it being paved in 1776.

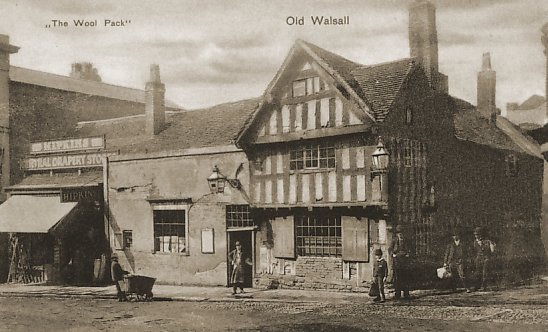

The Woolpack Inn. From an old postcard.

Other local pubs included the

Angel in Park Street, the Woolpack, and the Talbot,

both in Digbeth, the Three Swans in Peal Street, and

the Bull’s Head in Upper Rushall Street. The

Woolpack, a timber-framed building dating from the

15th century, was originally one of the finest

houses in the town. By the 17th century it had been

divided into an inn and a shop. The inn greatly

prospered because of its central position, and

became one of the main centres for cock fighting. It

survived until February 1964 when the area was

redeveloped.

The Green Dragon Inn in High

Street had been an inn since around 1707 and became

the centre of the town's social, and political life,

due to its close proximity to the Guildhall. It had

as large bowling green, 55 yards long, and assembly

rooms which were used as the town's first theatre

from around 1787 until 1803.

Improvements and Industrial

Uncertainty

By this time more traffic was

coming into the busy town centre. In order to

improve access from Birmingham Road, Bridge Street

(originally called New Street) was constructed in

1776. Until this time, all traffic to Birmingham had

to go through Digbeth and High Street to the top of

the town, and through Rushall Street. This was

treacherous, if not impossible in the winter

months, due to snow and ice.

Market house at the top of

High Street, built around 1589 was demolished in

1800. By the 1760s its position in the centre of the

road, close to the turning into Rushall Street, made

it an obstruction to traffic. It was replaced in

1809 by a smaller house further up the hill, near to

the church steps. By the 1830s it was little used,

and became a store for market stalls. It was

demolished in 1852.

In 1778 the Corporation added

extra pumps to the piped water supply that had been

in use since 1676. The new pumps were in Ablewell

Street, and Hill Top. There were pumps in each of

the main streets, and a wash house on The Bridge,

fed by lead water pipes from the source of the

supply at Caldmore, known as the ‘Spouts’. A workman

was paid an annual allowance of 10s.6d. to keep the

pumps in good repair.

By the latter part of the 18th

century the main industries in the town were chape

making, and buckle making. In 1792 it looked as

though buckle making would soon come to and end,

because buckles were rapidly going out of fashion,

due to the use of shoe laces, then known as

shoestrings. The Walsall buckle makers sent a

deputation to London, who were introduced to King

George III by prominent parliamentarian, Richard

Brinsley Sheridan, member of parliament for

Stafford. The King was sympathetic to their cause

and told the principal officers of his court that

they must continue to use buckles instead of

shoestrings. Other members of the royal family did

the same, and the deputation, which included buckle

makers from Wolverhampton, Birmingham, and London,

invited the chief members of the royal household to

a splendid dinner to celebrate their success. In

reality they were just delaying the inevitable. By

1820 the King and his household had ceased to wear

buckles, and a local newspaper announced that

“Walsall was ruined.”

The

George Hotel, Volunteers, and Increasing Population

The George Hotel opened in

1781. It was built by Thomas Fletcher who had

previously been landlord of the Green Dragon in

High Street. It became the most important coaching

inn in the town. At the height of the coaching era

it could stable 106 horses. Many coaches stopped

there daily, and many distinguished people stayed at

the hotel. Thomas Fletcher actively campaigned for

local roads to be improved, and helped to encourage

the series of Road Improvement Acts that were passed

by parliament in the late 18th and early 19th

centuries. He continued as proprietor of the hotel

until his death in 1811, when he was succeeded by

his son, Richard. In later times the hotel was

greatly enlarged and modified.

Walsall town centre in 1782.

Based on John Snape's map.

Walsall Volunteer Association

was formed in 1798 at a time when France was

threatening to invade the country. People from all

over the country were volunteering for the British

army, and Walsall was determined not to be left out.

A public subscription raised the necessary funds,

and a meeting was held in the Guildhall on May 12th,

1798, during which a letter from the Marquis of

Stafford was read. Forty three of the men who

attended the meeting joined the volunteers, who were

led by Joseph Scott, their captain. The colours were

presented at a ceremony held at Barr Beacon on

September 23rd, 1799. Afterwards the officers and

men were entertained at the George Hotel by the

Corporation, at a cost of 100 guineas.

Another association, the

Queen’s Own Royal Yeomanry, formed on July 4th,

1794, included a troop from Walsall, under the

command of William Tennant. In September 1800 the

Walsall troop, under the command of Sir Nigel

Gresley, helped to suppress riots at Walsall and

Wolverhampton caused by the high price of corn.

By 1801 the population had

grown to 10,399, divided almost equally between the

Borough and the Foreign (5,177 people lived in the

Borough, and 5,222 lived in the Foreign). The

Borough contained 1,013 houses, 135 of which were

uninhabited. There were 941 houses in the Foreign,

only 50 of which were uninhabited. There were more

women than men living in the Borough, and more men

than women in the Foreign.

Since the beginning of the

century the population had almost doubled, as it did

in the previous century, and Walsall had grown into

a sizeable Staffordshire town. The rate of

population growth hadn’t changed for two hundred

years, but in the next century things would be very

different as people flocked to the area to find

employment in the new industries that soon appeared.

By the middle of the next century there would be

around 30,000 people living in the town. |