|

Beginnings

Walsall probably began as a small village, surrounding

the parish church, on the top of the hill. It slowly

expanded down the hill alongside the market, and on the

other side of Walsall Brook, where Park Street is today.

By the end of the 14th century, buildings were appearing

in Park Street.

For much of its early life, it was

an agricultural town, surrounded by fields and meadows.

As was usual in the Middle Ages, there were common

fields, farmed in strips. Although the fields are now

long gone, some of their names remain as place names,

and street names. Long

Street alongside the railway line is near to the site of Long

Meadow, which belonged to the lord of the manor, and lay

between Walsall Brook and the mill race. Wisemore is named after

Wisemore Meadow, held by 4 tenants, later becoming a

common field. Other common field names were Holbrook

Field, which lay alongside, and to the south of The

Holbrook, and Churchgreve Field, which lay to the south

of Holbrook Field. The boundary between the two fields

was roughly where Chuckery Road is today. Chuckery is derived from Churchgreve,

meaning a small wood, which later became the common

field. Cow Lane is named after the lane leading from

Ablewell Street to Churchgreve, which at one time was

used as pasture for cattle, sheep, and horses. Another common

field which formed part of Churchgreve Field was The

Lee, possibly known as Lordeslegh. Butts Road is

probably named after some of the triangular areas in the

fields that did not fit into the ploughing scheme. They

were known as butts.

To the south of the town were

Vicar's Field, Windmill field, and possibly a field

called Armescote. In 1305 the town's windmill probably

stood in Windmill Field. It was owned by Sir Roger de

Morteyn, who in 1306 gave it to Henry de Prestwode and

his son John. In 1318 John sold it to Ralph, Lord

Basset, and it remained as the lord of the manor’s mill

until 1393 when it was destroyed in a gale. |

An impression of the early layout of the town.

|

The

Manor House and The Park

Park Street is named after the lord

of the manor’s park, which surrounded the manor house

and extended from the top of Park Street, later called

Town End, alongside the Willenhall Road, as far as

Bentley Mill to the west, and Pleck to the south. It

covered around 260 acres of land and had large numbers

of oak and chestnut trees. The park was created by

William Ruffus, who kept a herd of deer there. In the

14th century, Ralph, Lord Basset kept thoroughbred

horses there. They were from his stud at Drayton. In the

1380s bullocks and oxen were fattened in the park. At

this time it was mainly wooded, and enclosed to protect

the timber, some of which was used for Walsall pillory

in 1396-97 and for the perimeter fence.

The Belle Vue pub in Moat Road

stands on what was the northern side of the moat. The

site of the manor house is just behind the Belle Vue pub

car park. In between 1972 and 1974 an archaeological

excavation took place on the site of the manor house.

The remains of the buildings were very fragmentary,

having been disturbed by gardening. It

revealed that the original house had been built on

agricultural land, consisting of ridge and furrow. It

was built in the early part of the

13th century. The stone sills of three timber buildings

were constructed on the ridges, one of which contained a

latrine. Another was possibly a forge because slag was

found there. The slag is typical of iron-working, and of

the type that could have been produced in a bloomery,

although it could equally have been the result of heavy

smithy operations. The slag has a dense thin layer which

was probably produced at the bottom of a hearth furnace,

likely in contact with charcoal. |

|

A plan of the excavated buildings inside the

moat. |

Building A

was a rectangular structure, 4 m by 11 m, initially

built of unmortared limestone across one of the ridges.

Internally the furrows were filled with yellow clay. The

building was later reconstructed after a layer of clay

had been placed over the wall footings and the floor. No

hearth or features were found in the building. It

appears to have been a forge.

Building B

had a continuous base supporting a row of columns,

possibly in classical Greek style. It measured 3.5 m by

4.5 m with a half-width extension at the northern end,

measuring 1.6 m by 1.3 m. The floor was clay covered,

and spotted with charcoal. In the eastern wall was a gap

that led to a culvert, which ran outside the southern edge of the

building, possibly part of a latrine. A small pile of

triangular tiles was discovered at the southern end of

the building.

Building C

was not excavated, only two exploratory trenches were

dug, the first across the west wall, and the second

along the east wall. As in the other buildings, the

furrows were filled with yellow clay. A hearth was

discovered in the east wall. |

|

Remains of an east-west foundation

wall were found at the southern end of the site,

indicating the location of another building. Much of the

building had been robbed-out, but what was left

consisted of fragments of internal partitions, a bake

oven, and two patches of burnt clay, possibly hearths.

The building included a room measuring 5 m by 5.7 m, but

the remains were at best fragmentary. Parts of another

building to the east were found, including the

foundations of a rectangular chimney measuring 2 m by

2.4 m. Just outside the building was a wood-lined well,

2 m square.

There were indications of a

building to the south of the well, built of unmortared

limestone. Unfortunately it extended beyond the southern

limit of the excavation. The building with the bake oven

and hearths is thought to be the kitchen, the building

with the chimney, residential, probably the hall itself,

and the building to the south was possibly an open shed.

The construction of the moat seems

to have involved the diversion of a stream, which flowed

northwards along the west side of the site. The stream, now culverted,

still exists, and flows beneath the houses to the north

of the site. The north arm of the moat, and the northern

ends of the east and west arms had been filled-in

sometime before 1884 when a row of houses was built upon

them. During the second half of the 19th century the

southern part of the site was a garden containing two

ranges of greenhouses. In the 1920s a bowling green and

pavilion were built on the

northern part of the site, with allotments to the south.

The site was acquired by the West Midlands Regional

Hospital Board in 1972, for redevelopment.

The manor house was probably built by William Ruffus, at the same time as the creation of the park.

After William’s death in 1247 it passed to his eldest

daughter Emecina, then around 1275 it was taken over by

her son Sir William de Morteyn. After his death in 1283

it was passed on to his nephew Roger de Morteyn, and in

1314 to Ralph, Lord Basset of Drayton.

It seems likely that Ralph’s son

and daughter-in-law lived in the house, or at least

occupied it for a time, because his grandson and heir,

Ralph, was born in Walsall in 1333. Around this time a

moat with a drawbridge was built around the house. The

Basset family seem to have used the house for many years

because in 1388-89 the roof was repaired, and a wooden

belfry was built for the chapel. A new drawbridge was

built over the moat, and the large heavy gates were

reinforced with iron. After Ralph’s death in 1390 the

house may have only been used occasionally. It was

abandoned in the 1430s, and the fishing rights for the

moat, known as ‘le Mote’ were leased to the bailiff of

the ‘Foreign’. The house must have fallen into disrepair

because it had been demolished by 1576.

By the early 1400s much of the land

in the park was leased out, and cleared for agricultural

use. In 1859 part of the area was opened as a public

park called ‘Moat Garden’ using the moat as a feature.

But the venture was unsuccessful and the park soon

closed.

W. Henry Robinson mentions, in his

"Guide to Walsall", a once famous spring called "Alum

Well" which was in a field on the eastern side of the

moat. |

| |

|

| View a list of the Lords of

the Manor of Walsall |

|

| |

|

|

Park Street, The Bridge and Walsall

Mill

Park Street follows the line of the

old road from the manor house and park into the early

town. Town End at the top of Park Street was possibly

the ‘head of the town’ which is mentioned in the charter

of 1309, which allowed the burgesses of Walsall (the

higher status members of society), the right to hold

their own courts, and also began to regulate the

separation between the centre of Walsall (the Borough)

and the outlying areas, known as the Foreign. At Town

End, Park Street divided into three, one road leading to

the park, the manor house, Willenhall and Wolverhampton,

a second leading to Birchills, and a third leading to

Bloxwich.

The other end of Park Street led to

The Bridge, originally a small footbridge

across Walsall Brook, which now runs in a culvert. The

bridge was first recorded in the 13th century. Walsall

Brook flows southwards to Bescot Brook and the river

Tame, and is fed from the north by two streams, The

Holbrook, which rises near Rushall Canal, and Ford Brook

which flows from Aldridge. The confluence of the two

streams is near the Gala Baths. Just north of the old

footbridge, near to where Sister Dora’s statue now

stands, was the lord of the manor’s water mill, and the

mill pool, which extended from the brook across to the

area now occupied by St. Paul’s Church. The pool was

known as ‘The great fish stew’.

This may have been the great

fishpond of Walsall, which was owned by Emecina and

Geoffrey de Bakepuse, and in 1248 leased to her sister

Margery, and her mother Isabel, widow of William Ruffus.

In 1275 when Emecina’s son, Sir William de Morteyn, took

over the running of her estate, he acquired the

fishpond, which he owned until his death in 1283.

|

|

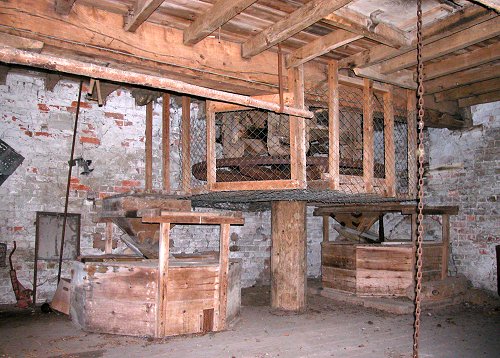

An impression of how the interior

of the mill may have looked. |

The water mill was known by

several names; Walsall Mill, Town Mill, the Ford Mill,

the Old Mill, and the Malt Mill.

In 1395-96 Jenkyn Cole, of Walsall

Mill complained that the burgesses of the town would not

grind their corn at his mill, instead taking it to other

mills including the one at Rushall.

He was advised to

get a more cunning miller to regain their goodwill.

By 1763 the mill had closed.

|

|

Early roads, and the early village

The track across the footbridge led

to what is now Digbeth and High Street, and on to the

parish church, and the original settlement. High Street

has been the site of the market since 1220 when a Royal

grant gave William Ruffus, Lord of the Manor, the right

to hold a weekly market on Mondays, and a fair on the

21st of September, St.

Matthew's day, and on its eve. In

1399 another fair was added on the 24th June and on its

eve, celebrating the Nativity of St. John the Baptist.

In 1417 market day changed to Tuesday when Richard

Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, and Lord of the Manor of

Walsall,

granted a Tuesday market, and two fairs every year, one

on October the 28th (St. Simon and St. Jude's day) and

another on May the 6th (the feast of St. John).

Walsall became an important market

town, selling mainly farming produce for many centuries.

By 1386 a market cross had been erected at the top of

High Street, in the centre of the road, near to its

junction with Upper Rushall Street, which probably

existed in the early 13th century as the road to

Lichfield. It had been named by 1339.

The road southwards from the

junction of High Street and Upper Lichfield Street, now

called Peal Street, was the road to Birmingham, West

Bromwich, Darlaston, and Wednesbury. It was known as

Hole End in the 14th century, and also Newgate Street.

Before the building of Bradford

Street in 1831, the route to Darlaston and Wednesbury

ran along Peal Street, Dudley Street, and Vicarage Place

to join the existing Wednesbury Road. The route to West

Bromwich started at Peal Street, and ran along New

Street, Sandwell Street, and West Bromwich Road. It was

certainly there well before 1452, because in that year

Thomas Mollesley left money for the building of a new

bridge (Tame Bridge) in West Bromwich Road, on the old

Walsall and West Bromwich boundary. The road to

Birmingham was probably in use by the middle of

the 13th century. It ran from New Street, through Birmingham

Street to Birmingham Road.

The parish church has stood at the

top of the hill since around 1200. It was originally

dedicated to All Saints, and still has its 13th century

crypt, which is the oldest surviving building in the

town. The church itself has been extensively rebuilt

since those early days, and must look very different to

its original form.

The initial settlement and the

early town grew up around the church, and would have

consisted of simple wooden buildings. Most occupants

lived in the town centre. The surrounding areas,

known as the ‘Foreign’, included Bescot, Caldmore, and

Walsall Wood, which were tiny hamlets with only a few

inhabitants, whereas Bloxwich, also part of the

'Foreign' was bigger.

The feudal system introduced by the

Normans ensured that the tenants had to fulfil their

obligations to the lord of the manor. They included

working his land, and harvesting his corn. It would have

been an extremely hard life. |

Medieval farming.

|

In the late 1340s, the Black Death,

or plague as it was known, swept through the country,

killing large numbers of people. It returned in 1361,

and again in the 1370s and 1380s, by which time only ten

percent of the working classes remained. This changed

the relationship between the lord and his tenants, and

brought about an early end to feudalism. Peasants were

now in short supply and many farming communities

disappeared. They could now dictate their own wage

levels and terms of employment. In 1401 the tenants in

Walsall refused to pay their rents in lieu of services

and went on strike.

Although the main occupation in the

town during the Middle Ages was farming, there is

evidence of industrial activity in the 14th century. In

1300 the Manor of Walsall was divided into two parts,

the first part owned by Roger de Morteyn, and the second

part by Margery Ruffus (le Rous). They agreed to share

the profits of the coal and ironstone mines in the

manor. Margery’s son, Sir Thomas le Rous reserved the

right to license coal-mining on land at Birchills in

1326 and 1327. By the late 1380s, and 1390s, there

were mines in Windmill field.

By 1300 there was a fulling mill at

Walsall, and cloth was made in the town by the middle of

the 15th century. In 1309 a charter granted by the lords

of the manor to the burgesses

stipulated that the market-place should be kept clean.

Charters and Burgesses

In the Middle Ages the higher

status members of the community were known as burgesses.

They were often the more skilled members of society, who

were householders,

and did not have the manorial obligations of serfs. They

paid rent and could run their own lives with more

freedom. They had special privileges that derived

from their support of the community, and played an

important part in the early life of the town.

In 1225 a charter granted by

William Ruffus gave the burgesses freedom from paying

most of the feudal tolls and customs, in return for an

annual fee of 12 marks of silver. He also allowed them

to keep their swine in the manorial park, to feed on the

acorns when they fell

from the trees. They were charged one penny per beast

for the privilege. A second charter granted in 1309 gave

them further benefits, including the right to hold their

own courts. They were an influential group of privileged

people, one of whom was the first mayor of Walsall,

although his name is not known. This is mentioned in the

Burgess Roll, which was kept from 1377 until 1619, and

presented to the town by Walter Sneyd, of Keele Hall. It also includes

a reference to Walsall’s first town council. It was only

possible to become a burgess, with the agreement of the

other burgesses, and the payment of a sum of money.

The Burgess Roll contains entries

relating to the admission of people into their group:

Walter Fletcher came amongst the

said Burgesses and gave them 2s.4d that he might enjoy

the freedom of the Burgesses of the town aforesaid, as

in a certain Charter by the Lords of the Manor of

Walsall, to them thereof granted is more fully

contained. And he did fealty to the Burgesses…..

Roger Mollesley was received as a

Burgess, and gave 2 shillings for a fine…….

Henry Mylleward de Ruschale was

received as a Burgess, and gave for a fine 6s.8d because

he was not of the Manor, nor Tenant within the Manor.

Richard Bridgend of Rushall Street

was received as a Burgess to this extent, that he might

enjoy etc., and he gave 6s.8d for a fine, and did fealty

to the Burgesses.

Henry Marchall of Walsall was

received as a Burgess, and paid forthwith 6s.8d, and did

fealty to the Burbesses.

Richard Wever, heir to the

aforesaid Henry, was received a Burgess by descent from

the aforesaid Henry Marchall. (Wever was probably the

son of Marchall’s daughter)

It seems that prospective members

who lived within the Borough had to pay 2s.4d to join,

whereas people living in the Foreign were charged 6s.8d.

The Foreign Burgesses received the full privileges that

had been given to the other members, including immunity

from paying tolls.

They had many privileges including

the right to keep animal pens at the market, and the use

of common pasture in the waste, which consisted of

several commons including Birchills, Blakenall, Dead

Man's Heath, Pleck, Short Heath, and Wallington.

It seems that there must have been

a school in Walsall in 1377 because a schoolmaster named

Robert became a burgess in that year.

|

|

By the 15th century the hall of St.

John’s Guild in High Street (built by 1416) became the

seat of local government. The Guild of St. John was founded in the late 14th century, as a religious

organisation with a special alter in the parish church.

It had a social and political role, and was closely

associated with the town council. Many members of the

guild were burgesses.

On the 6th October, 1399 King Henry

IV gave a grant to the men of Walsall which freed them

from the payment of tolls when travelling anywhere in

the country. This privilege was enjoyed by many other

towns including Wednesbury and Coventry. It seems that

the charter was granted as a concession to Thomas de

Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, and Lord of the Manor of

Walsall, after his titles and estates were restored to

him. He was one of the Lords Appellant who tried to

separate King Richard II from his favourites in 1387.

Richard saw him as a potential enemy, and charged him

with high treason in 1397, supposedly as a part of the

Earl of Arundel's alleged conspiracy. |

The arms of Thomas de Beauchamp. |

|

Beauchamp was imprisoned in the

Tower of London, in what is now known as the Beauchamp

Tower. He pleaded guilty, and forfeited his estates. He

threw himself on the mercy of the king, and was

sentenced to life imprisonment on the Isle of Man. In

1398 he was moved back to the Tower, where he stayed

until his release in August 1399. Henry Bolingbroke had

deposed the king and became King Henry IV, who restored

Beauchamp’s titles and estates, and gave the grant to

the men of Walsall.

A curious code of laws was made in

the Borough in the 15th century, for the “continuance of

gode rule”. It regulated the playing of “unlawefull games,

except in Cristemas, as dyce, tables, cares, cloch,

tenes, foteball, or eny other lyke”.

An important benefactor was Thomas

Mollesley of the Manor of Bascote, who died in 1451. He

arranged that after his death, a dole was to be given out

in his memory, and distributed to every man, woman, and

child, resident in the Borough and Foreign of Walsall.

It was administered by the Guild of St. John, and given

out on Twelfth Night (6th January). The dole was

distributed every year until 1825. Distributors visited

every house, and gave one penny to every person in the

Manor. Legend has it that Thomas Mollesley was riding

through Walsall on the day before Twelfth Night and

heard a child crying for food. He decided to bequeath

his land at Bascote so that this could never happen

again.

Walsall took its Coat of Arms,

which includes the Warwick emblem of the "Bear and

Ragged Staff" from the town’s association with the Earls

of Warwick, who were lords of the Manor of Walsall for

nearly 100 years.

By this time Walsall was a

thriving, and growing market town, with a successful

farming community, and the beginnings of its industrial

future. There were 367 poll-tax payers in 1377. It was

an affluent town with a complex social structure, a town

council, and a bright future ahead.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Origins |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to 16th, 17th centuries |

|