|

The growth of industry and commerce

in the Black Country was made possible by a great

improvement in the roads, and the building of canals and

railways. This allowed raw materials to easily be

brought into the region, or transported around it; and

finished products to be quickly delivered to many parts

of the country.

Roads

Walsall was at a disadvantage when

compared to neighbouring towns. The roads were in a

particularly bad condition, and were described as

narrow, tortuous, and ruinous. They were ill-kept and so

narrow that in most places there was not enough room for

two vehicles to pass each other. The situation was made

worse by the hilly nature of the town.

Much of the traffic passed along

High Street, either ascending or descending the steep

hill, which in winter months became impassable due to a

large sheet of ice produced from the water that came

from the pump at the top of the street. The sharp turn

into Rushall Street at the top of the hill was also

difficult because it was only about ten feet wide. |

| In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, roads were

improved and maintained by turnpike trusts, which were

bodies set up by individual Acts of Parliament. The trusts

had powers to collect tolls to maintain roads, and often

erected toll houses for the purpose.

A trust was established for 21 years, after which the

responsibility for the road would be handed back to the

local parish. Often trusts would apply for an extension, and

exist for a longer period.

They were known as turnpike trusts because of the

similarity of the gate which controlled access to the road,

to the turnpike barrier used to defend soldiers from attack

by cavalry. |

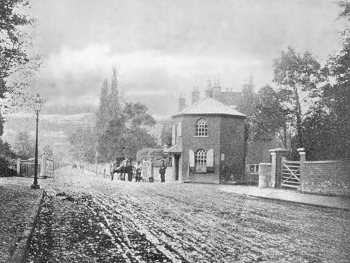

The toll house and toll gate, Penn

Road, Wolverhampton.

|

| By the 1830s there were more than 1,000 trusts,

maintaining around 30,000 miles of road in England and

Wales. From 1766 trusts were required to build milestones to

indicate the distance between principal towns on the road.

Road users were obliged to follow new rules of the road,

including driving on the left, and not damaging the road

surface. By the 1740s the dangerous state of the roads in

Walsall, and the high cost of carriage caused severe

problems for the emerging industries. The first turnpike Act

affecting Walsall was passed in 1748 as a result of a

petition from Wolverhampton and the surrounding areas for

improved roads between Birmingham and Wolverhampton, which

included the road to Sutton Coldfield, and the road from

Sutton Coldfield Common to Walsall. Sadly little had been

done by 1769 when the powers of the trust expired. The roads

were still in a bad state, and continued to deteriorate.

In 1766 an enquiry was held into the poor condition of

local roads. Mr. Jacob Smith was examined, and stated that

“the roads leading out of the town were very ruinous, narrow

and incommodious.” Mr. Joseph Curtis said that he thought it

“the worst town to pass through he ever saw.” The Rev. Sir

Richard Wrottesley stated that he “has been stopped an hour

by a carriage which was unloading, before he could pass in

his post-chaise.” After the enquiry a turnpike Act was

obtained, and before the year was out, the roads from

Walsall to Lichfield, Walsall to Dudley, Walsall to

Darlaston and Wednesbury, Walsall to Churchbridge, and Pleck

Road were turnpiked.

Under the terms of the Act, Ablewell

Street was to be repaired, and Bridge Street (originally

called New Road) was ordered to be built. The Act states

that “it would be of great public convenience if a road was

made from the ‘Brook’ in Walsall over certain lands to

Ablewell Street, and if Ablewell Street was repaired as far

as the turnpike road leading from Walsall to Birmingham.”

The new route bypassed Digbeth and High Street, and greatly

improved the route into the town from the south east.

Islington toll house and toll gate.

From the Illustrated London News.

The improved roads had a great impact

on traffic, which soon increased through the town. It was a

good time for coaching inns because of the increased number

of coaches that now travelled via the town. Aris’s

Birmingham Gazette of 30th November, 1778 includes an

advert for the Shrewsbury, Wolverhampton, Walsall, and

Birmingham Fly. The fare from Walsall to Birmingham was

£1.7s.0d inside, or 13s.6d. (half fare) outside. In 1780 a

coach ran from Holyhead to London via Walsall and

Birmingham. The fare from Walsall to London was £1.11s.6d.

In 1784 Mr. Fletcher of the recently

built George Hotel, obtained an Act of Parliament for the

building of the road from Walsall to Stafford, and the

widening of the Birmingham Road as far as Hampstead Bridge.

In 1788 a turnpike Act provided for the repair and

improvement of the roads to Wolverhampton, Sutton Coldfield,

and Hampstead Bridge. It also allowed the reconstruction of

the Birmingham Road. Another turnpike Act, Passed in 1793

allowed the road from Churchbridge to Stafford to be

improved. This reduced the journey to the north by four

miles and greatly improved the town’s link with Chester,

Liverpool, and Manchester. It also encouraged traffic

heading north from Birmingham to pass through the town,

increasing the prosperity of the local inns and shops.

In 1831 Bradford Street was built to

provide a shorter and easier route to Darlaston and

Wednesbury.

Canals

The local canal network, the Birmingham

Canal Navigations (BCN) was built to transport coal from the

Black Country coalfields in the Wednesbury area into

Birmingham. James Brindley surveyed a possible route in 1767

and during the following year an Act of Parliament was

passed to allow the construction to go ahead. James Brindley

was appointed as engineer to the newly formed Birmingham

Canal Company, and work soon got underway. The section from

Birmingham to Wednesbury opened on 6th November,

1769. The canal reached Wolverhampton in August 1771, and

the final section to Aldersley Junction opened on 21st

September, 1772, just 8 days before Brindley's death. The

canal was a great success. Large quantities of coal,

limestone, sand, and Rowley ragstone were transported far

more cheaply and quickly than ever before, benefiting both

the canal company and the mining companies alike.

Rushall Locks. |

|

The Walsall Canal

In 1770 an attempt was made to form a

company to build a canal from Walsall to the Trent and

Mersey Canal near Lichfield. A meeting was held at the

Bull’s Head in Walsall to get the project underway, but it

never materialised.

The first canal to reach the outskirts

of Walsall town centre, the Wyrley & Essington Canal was

planned to link the coalfields of Wyrley and Essington to

the Birmingham Canal at Wolverhampton. An Act of Parliament

was passed on 30th April, 1792 to allow the work to

commence. Much of the finance came from Wolverhampton

businessmen, principally the Molineux family. Work soon

started under the canal company's engineer, William Pitt.

There were two branches, one to a colliery at Essington and

the other to Birchills. The canal joined the Birmingham

Canal at Horseley Fields in Wolverhampton, and opened on 8th May, 1797. In 1840 the canal was acquired by the BCN.

In 1794 another Act was passed to allow

the company to extend the canal to join the Birmingham &

Fazeley Canal. As a result the canal extended from Birchills,

through Bloxwich, Pelsall and Brownhills to the Birmingham &

Fazeley Canal. Being a contoured canal and following an

extremely circuitous route, it became known as "The Curly

Wyrley".

When the building of the new canal was

announced, the Birmingham Canal Company began to think about

building a canal from the end of the Broadwaters Extension

to Walsall via Darlaston. |

|

| On 17th April, 1794 an Act of Parliament was passed to

allow the work to begin, and in 1799 the Walsall Branch of

the Birmingham Canal Navigation opened from Walsall Town

Wharf, near Marsh Street and Navigation

Street, to Moxley, which was used as a base for

the many navvies that were involved in the work. The locals

far from welcomed them, except for the publicans and beer

sellers. One of the larger features is James Bridge aqueduct

which carries the canal over Bentley Mill Way and the River

Tame. This was completed in 1799 and is now a listed

building. The Walsall Branch, the first through route

between Walsall and the Birmingham main line was completed

in 1809. The final link in Walsall’s canal

network, which opened in 1841, joined the Birmingham Canal

to the Wyrley and Essington Canal. It allowed coal to be

brought from the Bloxwich and Pelsall coalfields into the

Walsall basin.

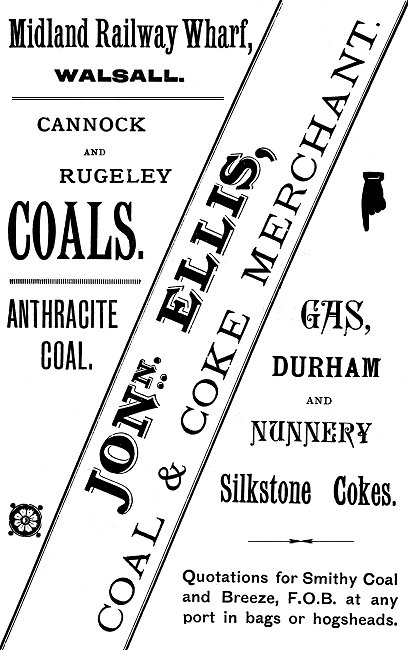

Some adverts from 1899:

Railways

Following the success of the Liverpool

& Manchester Railway, which opened on September 15th 1830, many schemes were

proposed for the building of other railways. The earlier problems due to

lack of capital no longer applied and investors were easy to find. Other

towns and cities could see the benefits that would come from better links between

the nation's centres of commerce and industry. Birmingham businessmen were planning a

link to London, and the group of financiers that were involved with the

Liverpool & Manchester Railway could see that Birmingham would be an ideal

goal for expansion. In 1831 the Warrington & Newton Railway opened and

ran about 5 miles southwards from Newton Junction at the centre of the

Liverpool & Manchester Railway to Warrington, and the River Mersey. This

was considered to be an ideal starting point for a route to Birmingham, and

after much surveying, a route was found that was practical and avoided conflicts

with landowners.

The Bill for the Grand Junction

Railway, which was named after the Newton Le Willows junction, was passed in

Parliament on May 6th, 1833. This was the same day on which the Bill for the

London & Birmingham Railway was passed, and so work on the line quickly

proceeded.

Three engineers were employed to share

the engineering duties. They were George Stephenson, who was in overall

control, Joseph Locke, who looked after the construction of the northern

half, and John Rastrick who looked after the construction of the southern half.

Joseph Locke was determined to prove himself and laboured

vigorously in the construction of the line. Stephenson and

Rastrick were involved in other work, and not fully

committed to the project. Rastrick resigned in 1833, and

Stephenson resigned in 1835.

The last 14 miles were quite

troublesome and produced many unexpected problems. The first

was a small aqueduct carrying the Bentley Branch of the

Birmingham Canal across the Darlaston Green Cutting. A

temporary canal was built as a diversion while the aqueduct

was built. It used a cast iron liner to contain the water,

but when it was filled, a severe leakage developed. The

canal had to be re-diverted so that the problem could be

solved. This took a great deal of time and was the last part

of the construction work to be completed.

On the outskirts of Birmingham a detour

was needed around Aston Hall which required a further Act of

Parliament. This resulted in the hasty design and

construction of several extra bridges, viaducts and

embankments, which greatly increased Locke's workload. The

construction of the line in record time was a great

triumph for Locke. The average cost being less than the

estimated £20,000 per mile, which was very cheap when

compared with the £46,000 per mile for the London &

Birmingham Railway. |

Walsall's early railways.

|

1st and 2nd class fares from Bescot Bridge.

|

Considering that this was the first

long-distance line in the world, its opening on

July 4th, 1837 was a

very quiet affair. A train pulling 3 coaches and a mail

coach set off from Liverpool, and a similar one set off from

Manchester. They met at Newton Junction where both trains

were combined and hauled southwards to Birmingham by the

locomotive ‘Wildfire’.

The local stations were as follows:

Wednesfield Heath (for Wolverhampton),

Willenhall, James Bridge (for Darlaston), Bescot Bridge (for

Walsall and Wednesbury), Newton Road (for West Bromwich),

Perry Bar, and Birmingham (Curzon Street)

Bescot Bridge, also known as Walsall

Station was the town’s first railway station. It stood on

the Wednesbury road near to the borough boundary.

A branch

to Walsall had been planned, but was not built. Passengers

travelled between the George Hotel and the station in a

small yellow one-horse omnibus in the charge of John Cox.

There were two trains daily, each way. Bescot Bridge Station closed in 1850,

and was reopened in 1881 as Wood Green Station. It finally

closed in 1941. |

|

Walsall’s first station in the town centre

The South Staffordshire Railway was

incorporated on 6th October, 1846 by an amalgamation

of two companies, the SS Junction, and the Trent Valley,

Midlands & Grand Junction. They had powers to construct

railway lines from the Oxford, Worcester & Wolverhampton

Railway at Dudley, to Walsall, and on to the Midland Railway

at Wichnor. There were to be spurs from Pleck to James

Bridge, to the Grand Junction Railway at Bescot, and the

Trent Valley line at Lichfield.

Work began at Walsall on the section to

Dudley. The first part from Walsall to the Grand Junction

Railway at Bescot (1¾ miles long) opened on 1st November, 1847, with a temporary station at Bridgeman Place,

off Bridgeman Street, opposite the junction with Station

Street. There were four trains each day running between

Walsall and Birmingham Curzon Street. Trains left Birmingham

at 9 a.m., 11 a.m., 4 p.m., 7.15 p.m., and left Walsall at

9.50 a.m., 11.30 a.m., 4.45 p.m., and 8.30 p.m. They were

worked by the newly formed London & North Western Railway,

founded on 16th July, 1846 by an Act of Parliament

which allowed the amalgamation of the Grand Junction

Railway, the London & Birmingham Railway, and the Liverpool

& Manchester Railway. Trains from the northern part of the

London & North Western Railway were still met at Bescot

Bridge by John Cox and his omnibus.

|

| A view of Walsall.

From Osborne's Guide to the Grand

Junction Railway, 1838. |

|

|

Building work on the new railway

continued towards Dudley, which had to be reached by 1st

November, 1849. The Act stated that if the company failed

to reach Dudley by that date, the Birmingham, Dudley &

Wolverhampton Railway would have running powers into Dudley.

The line was completed just in time, and a special train ran

from Pleck to Dudley on the day of the deadline. Because the

stations were far from complete, regular services didn’t

start until the following year. Goods services began in

March, passenger services on 1st May.

While this had been going on, work

progressed on the northern section from Walsall to

Lichfield, through Alrewas, and to Wichnor Junction, then on

the Midland Railway line to Burton-on-Trent. The new line

opened on 9th April, 1949. It was 17¼ miles long.

Work on the northern section also

involved the building of Walsall’s first permanent railway

station in Station Street, a Jacobean-style building

designed by Edward Adams of Westminster. When the new line

opened, a celebration dinner was held at Lichfield, along

with a ball at the Guildhall. The new station was

incorporated into the 1884 extension to Park Street. It

was burnt down during a severe fire in 1916, and later

rebuilt. It reopened in 1923, and survived until demolition

in 1978, when the existing station was built.

At this time the company began to use

its own locomotives and rolling stock. 29 locomotives were

purchased from several manufacturers, many of which were

named after local towns. They were as follows:

|

|

No. |

|

Name |

Manufacturer |

Details |

| 1. |

|

Dudley |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

2-2-2 single |

| 2. |

|

Walsall |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

2-2-2 single |

| 3. |

|

Wednesbury |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

2-2-2 single |

| 4. |

|

Lichfield |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

2-2-2 single |

| 5. |

|

Burton |

Sharp Brothers & Company, Manchester |

standard 5ft 6in. single |

| 6. |

|

Stafford |

Sharp Brothers & Company, Manchester |

standard 5ft 6in. single |

| 7. |

|

Bescot |

Sharp Brothers & Company, Manchester |

standard 5ft 6in. single |

| 8. |

|

Birmingham |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler |

| 9. |

|

Wolverhampton |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler |

| 10. |

|

Belvidere |

W. J. and J. Garforth, Manchester |

tender goods engine |

| 11. |

|

Angerstein |

W. J. and J. Garforth, Manchester |

tender goods engine |

| 12. |

|

Pelsall |

Robert Stephenson & Company, Newcastle |

6 coupled, long boiler |

| 13. |

|

Alrewas |

Robert Stephenson & Company, Newcastle |

6 coupled, long boiler |

| 14. |

|

Sylph |

Sharp Brothers & Company, Manchester |

standard 0-4-2 |

| 15. |

|

Safety |

Sharp Brothers & Company, Manchester |

standard 0-4-2 |

| 16. |

|

Viper |

E. B. Wilson & Company, Hunslet, Leeds |

0-6-0 goods engine |

| 17. |

|

Stag |

E. B. Wilson & Company, Hunslet, Leeds |

0-6-0 goods engine |

| 18. |

|

Esk |

E. B. Wilson & Company, Hunslet, Leeds |

2-4-0 goods engine |

| 19. |

|

Justin |

E. B. Wilson & Company, Hunslet, Leeds |

2-4-0 goods engine |

|

20. |

|

Priam |

Charles Tayleur & Company,

Vulcan Foundry,

Newton-le-Willows |

goods engine |

|

21. |

|

Ajax |

Charles Tayleur & Company,

Vulcan Foundry,

Newton-le-Willows |

goods engine |

| 22. |

|

Bilston |

Beyer, Peacock & Company, Gorton, Manchester |

front coupled tender engine |

| 23. |

|

Derby |

Beyer, Peacock & Company, Gorton, Manchester |

front coupled tender engine |

| 24. |

|

Cannock |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| 25. |

|

Bloxwich |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| 26. |

|

McConnell |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| 27. |

|

Vauxhall |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| 28. |

|

Aston |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| 29. |

|

Tipton |

William Fairbairn & Sons, Manchester |

6-coupled, long boiler goods |

| The carriage and wagon stock was

obtained from Joseph Wright and Sons,

Saltley, Birmingham. |

|

Number 1.

Dudley.

Carrying its later L&NWR number

297. |

| Number 16.

Viper.

Carrying its later L&NWR number

301. |

|

|

Number 19.

Justin.

Carrying its later L&NWR number

181. |

|

In 1850 an Act of Parliament was passed

to allow the South Staffordshire Railway board to lease the

railway to the company’s engineer John Robinson McClean for

21 years. The railway company realised that the amount of

traffic on the line would probably fall when the London &

North Western Railway’s Stour Valley Line opened. Under the

terms of the lease McClean had to pay a deposit of £10,000,

and guarantee a clear dividend of 2 percent in the first

year, and 4 percent afterwards, rising to 5 percent after 14

years.

The next development on the line took

place when McClean obtained mining concessions in the

Cannock coalfield and used the railway to transport his

coal. He built a new branch to Cannock with stations at

Bloxwich, Wyrley & Church Bridge, and Cannock.

In 1861 McClean relinquished his lease

to the London & North Western Railway, which immediately

entered into a battle with the Midland Railway over its

section from Wichnor Junction to Burton-on-Trent. The

Midland relented, giving full running powers to the London &

North Western, but would soon begin to play an important

role in Walsall’s rail network.

The

Wolverhampton & Walsall Railway

By the 1860s most of the local

manufacturing towns were easily and quickly accessible by

train from Wolverhampton. Two notable exceptions were

Willenhall and Walsall. Although they already had railway

stations, it was necessary to change trains during a

circuitous journey. An end to the tedium was in sight when

the Wolverhampton & Walsall Railway was incorporated on 29th June, 1865.

The route was 8 miles long and took 7

years to complete, with four intermediate Acts being passed

before the operation began. The line started at

Wolverhampton High Level station and ended at Walsall, with

five intermediate stations in between. They were at Heath

Town, Wednesfield, Willenhall, Short Heath, and

North Walsall in Bloxwich Road. The railway opened on 1st November, 1872 and was operated jointly by the London

& North Western Railway and the Midland Railway.

Disagreement arose between the two

companies and legal proceedings followed, which resulted in

the L.N.W.R. buying the Wolverhampton & Walsall Railway in

1875. The London & North Western realised that they would be

able to sell the line to the Midland Railway for a profit

because of the building of the Wolverhampton, Walsall &

Midland Junction line. This was an extension from the

Midland mainline onto the Wolverhampton & Walsall Railway,

and would provide a direct route into Wolverhampton for the

Midland Railway. The line was sold to the Midland Railway on

1st June, 1876. On 31st July, 1876 the L.N.W.R. ceased to

run services on the line.

|

|

Birmingham's first railway

station. From Drake's Road Book of the Grand Junction

Railway, 1838. |

|

The Wolverhampton, Walsall & Midland

Junction line, and the Walsall & Water Orton line, which

joined the Midland mainline, opened on 1st July,

1879. The Midland Railway now had a direct route into

Walsall, and built its own goods yard on the site of the old

racecourse.

The Midland’s running powers into

Wolverhampton High Level station ended on 30th June

1878 and the company decided to build a railway station for

passengers in Wednesfield Road. An Act of Parliament

allowing construction was passed on 28th June, 1877,

but in the end the company built a goods depot instead.

By the time the local rail network had

been completed, Walsall had all of the necessary links in

place to ensure that its manufacturers could easily and

quickly acquire raw materials, and that the finished

products would be rapidly transported to destinations

throughout the country. The improved roads and the railway also had an impact on the town

centre, and the market. For the first time shoppers could

easily travel there, and so new shops appeared, and the town

became more prosperous. Thanks to the railway, locals began

to travel to more distant places for holidays and days out.

Excursion trains for both adults and children were well

supported. An early popular destination was Lichfield and

its cathedral. |

An advert from 1896.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to The

18th Century |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to Religion |

|