Churches and Religion

|

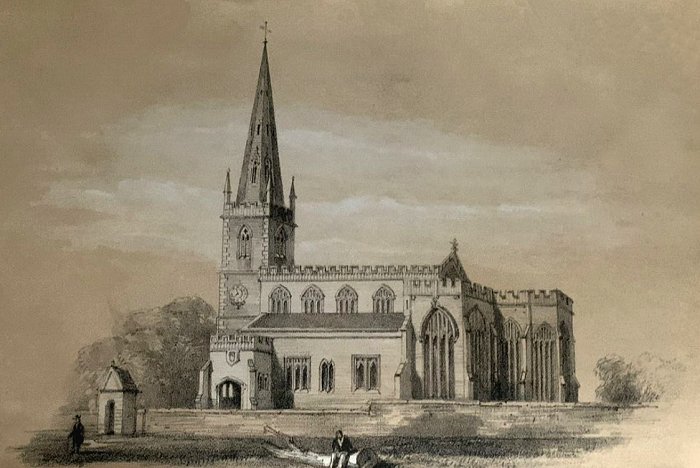

St. Bartholomew’s Church There was certainly a church at

Wednesbury by the early thirteenth century because it is

recorded in the Plea Rolls of King John for 1210-1211,

that Master William, a royal chaplain had been appointed

to the church at Wednesbury.

The present St. Bartholomew’s

Church dates from the late 15th or early 16th

century and contains a pulpit carrying the date 1611.

At the west end of the nave is a

table tomb with recumbent effigies of Richard Parkes who

died in 1618, and his wife.

It has been greatly restored and rebuilt, and

stands on the site of an earlier 13th century

stone built church. |

St. Bartholomew's Church. |

|

|

St. Bartholomew's Church. |

Remains of the

earlier church were found during restoration work in

1885 and consisted of a three light window contained in

a round-headed arch. The three lights date back to the

13th century but the

arch itself could be earlier.

The ancient window is to

be found at the west end of the north aisle. It is next

to the doorway which gives access to the choir vestry.

This has a pointed segmental arch and is said to be from

the same date as the window.

In 1757 the tower was

restored and the top 16 feet were rebuilt. At the same

time the ball and weathercock were replaced. Restoration

work continued in 1764 and 1765 when the nave roof was

repaired and a ceiling added to the nave.

Unfortunately

during the work, part of the parapet on the northern

side collapsed onto the roof and both fell onto the pews

beneath, causing serious damage. As luck would have it

the pews were empty at the time. Only an hour earlier

they had been occupied during a funeral service. |

| As the parapet on the south side was found to be in

an extremely poor condition, the decision was taken to

rebuild both parapets and also to add a ceiling above

the north aisle.

As the restoration was now much larger

and so more expensive than previously envisaged, neighbouring parishes were invited to make collections

towards the cost of the work.

In 1775 part of the south

transept was enclosed and a wall added to form a vestry,

and in 1818 the body of the church was coated with

Parker’s cement.

Nine years later the church was enlarged by the

addition of the north transept and an extended nave. The

pews were also replaced and a new font was presented by

the Rev. Isaac Clarkson in 1827.

Restoration work continued in 1855 when the upper

part of the spire was completely rebuilt and the 8 bells

were recast.

Two new bells were also added, along with a

new clock and weathercock. The cost of the repairs was

raised by subscription and amounted to nearly £1,200. |

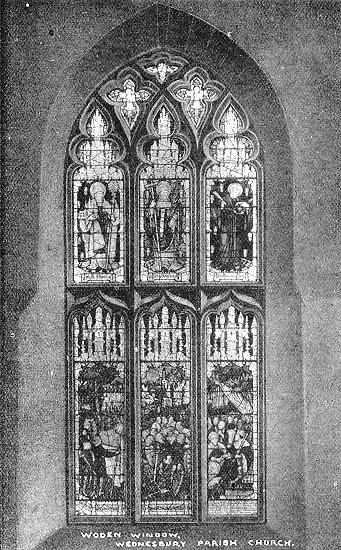

The Woden window in St. Bart's

Church. |

|

In 1878 the spire was raised by 10

feet, and in 1885 the internal galleries were removed

and the floor lowered to its original level.

Further restoration work took place in 1902 and 1903

when the transepts were restored.

In 1913 the Chapel of

Ascension was added to the south transept. The church contains 15 late 19th or

early 20th century windows containing

stained glass by

Charles Eamer Kempe and is also known for its unique

fighting cock lectern. On 2nd March,

1950 the building was Grade 2 listed. |

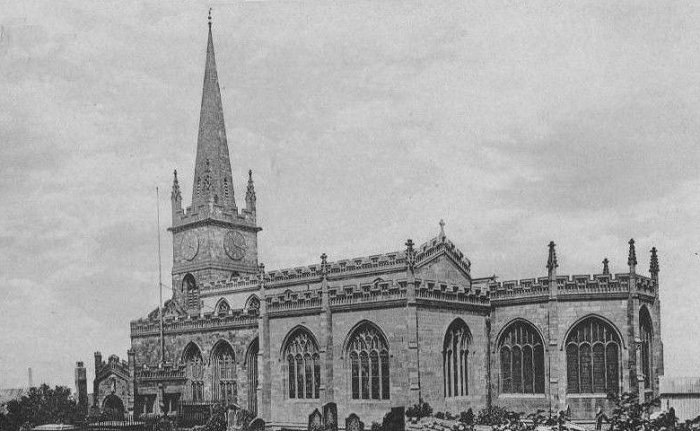

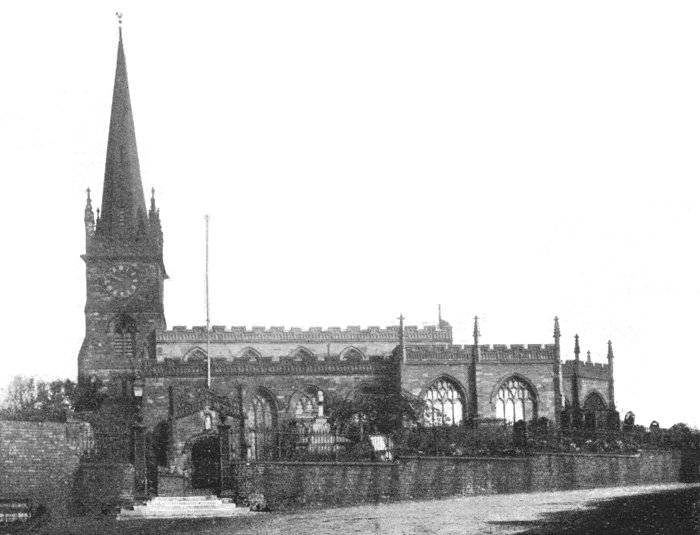

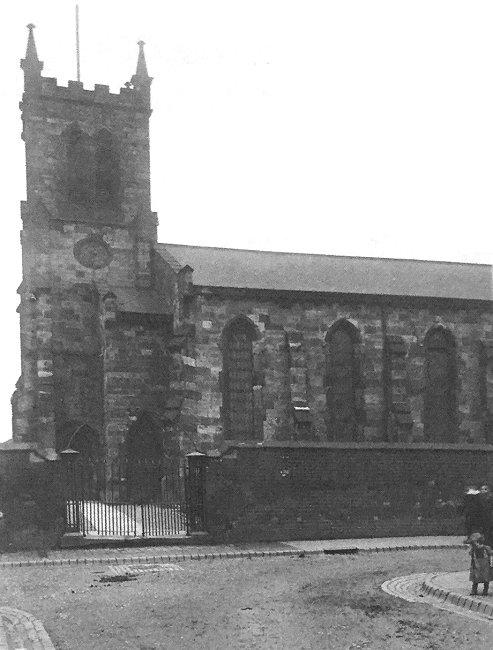

St. Bartholomew's Church from

Ethelfleda Terrace. |

|

St. Bartholomew's Church, as seen

from Church Hill. |

|

St. Bartholomew's bells.

|

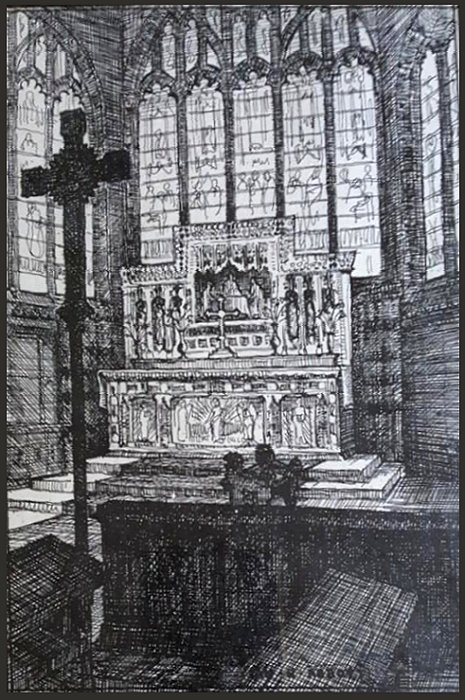

A fine pencil

sketch of the church interior, entitled,

'Alter and Reredos, Wednesbury Parish

Church, Ian Abbott 49'.

If you have any

information about Ian Abbott, please

send me

an email. |

A view of St. Bart's Church from

1908.

St. Bartholomew's Church, as seen in 1933. From an old

postcard.

The interior of St. Bart's Church

in 1908.

Another view of the interior. From

an old postcard.

An image of St. Bartholomew's

Church from an 1854 history of Wednesbury.

Another view of St. Bartholomew's Church.

A final view of St. Bartholomew's Church.

St. John’s

Church

In 1843 an Act of Parliament, commonly known as Sir

Robert Peel's Act was passed. Its purpose was to make

better provision for the spiritual care of populous

parishes. The vicar of Wednesbury, the Rev. Isaac

Clarkson took advantage of the act and instigated the

formation of three new ecclesiastical parishes; St.

John's, St. James's, and Moxley, which were created on

3rd June, 1844. The Rev. John Winter was appointed as

the first vicar of the parish of St. John and services

were held in a carpenter’s shop and then in the People’s

Hall. |

|

St. John's Church. |

|

Building work on the new church in Lower

High Street began in 1845, supported by Edward Thomas

Foley, Member of Parliament for Herefordshire, and

one-time High Sheriff of Herefordshire. The land was

given by Samuel Addison, along with a gift of £500 for

the building fund, and £700 for the spire. The

foundation stone was laid by Lady Emily Foley on

Thursday 27th March, 1845.

The stone building was built in the early English

style using the local yellow-brown peldon sandstone from Monway Field. The building

consisted of a western chancel, a nave with 6 bays, a

clerestory, aisles, a north porch, and a south-eastern

tower, with a spire and one bell. The architects were

Messrs. Daukes and Hamilton, and the builder was Mr.

Isaac Highway of Walsall. The site and the building cost

£5,758.6s.4d. which was raised with the help of grants

from the Lichfield Diocesan Church Extension Society,

and the Incorporated Society for Building Churches and

Chapels.

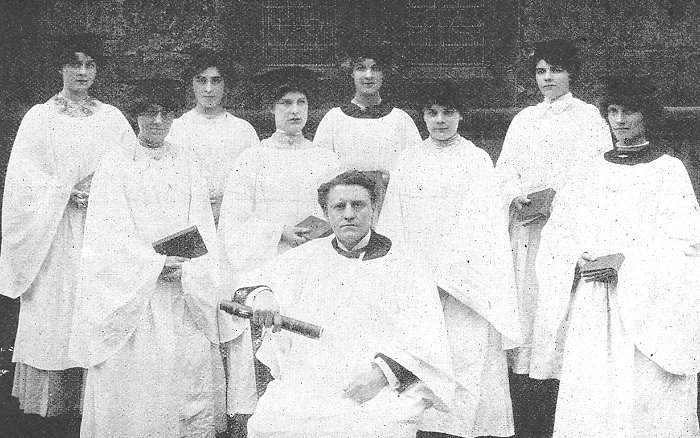

St. John's lady choristers in

1905.

|

|

The church seated 1,000

people and was consecrated on 13th May, 1846, by the

Bishop of Lichfield. An organ was presented to the

church by James Bagnall and Thomas Walker, and gas

lighting soon added.

Mrs. Elwell of Wood Green presented

the church with the carpet within the alter rails, Mrs.

Fletcher of Dudley gave the linen for the communion

table, and the books for the minister were presented by

the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

£300 a year was provided for the vicar,

£150 a year was provided by the Ecclesiastical

Commissioners, and other funds came from Wednesbury

Parish tithes. Rents were paid for the pews, which were

given to the vicar, less £6 a year for the church clerk.

The church's patron was Lady Emily Foley. |

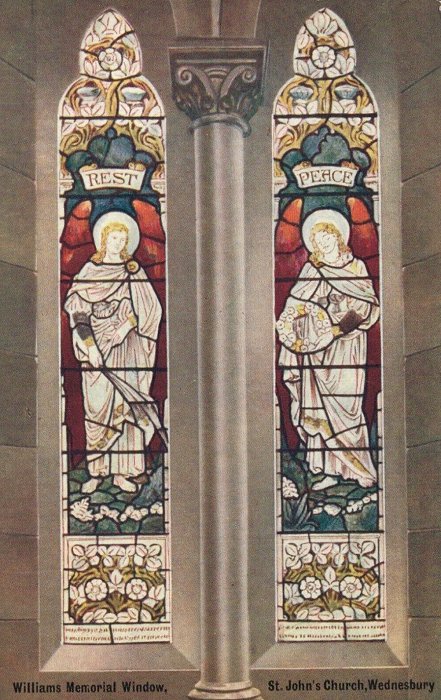

From an old postcard. |

|

St. John's Church. |

St. John's Parish Schools were built in

1848-1849 at a cost of £1,158.10s.2d., including the

fittings and the site. The school opened on the 11th

March, 1849 and had accommodation for 300 children. It

was both a Sunday and a day school. In the 1850s the

population of the parish was around 2,500.

A parsonage was built in 1893 and stood on part of

the site previously occupied by the Legs of Man Tavern.

At the time the church tower contained the only

illuminated clock in the town and was given by Edward

Smith to commemorate the Queen’s Jubilee. Restoration

work carried out during the church’s golden jubilee in

1896 included the decoration of the interior, the

provision of an organ chamber, and external repair work.

The building became derelict in 1980 and was

demolished in July 1985. |

|

St. James’ Parish was created on

3rd

June, 1844 along with the parish of St. John.

The first

building to be constructed on the site, in St. James

Street was the parish school, which opened in March 1845.

It was built at a cost of £1,126.19s.0d. including the

cost of the land, and the residence for the master and

mistress. Church services were initially held there until the the

opening of the church.

In January 1847 a committee was

formed to oversee the building of the church. The laying

of the foundation stone took place on 26th May, 1847 and the

building was consecrated on Wednesday 31st May,

1848.

The church, built in early English style, with the

same local stone as St. John’s, cost £3,405, and seated

835 people.

The building consists of a nave, aisles, a

chancel with an apse, a vestry, south porch, and a tower

with a clock, chimes and one bell.

|

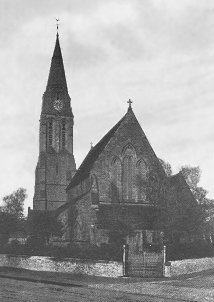

St. James' Church. From an old

postcard. |

|

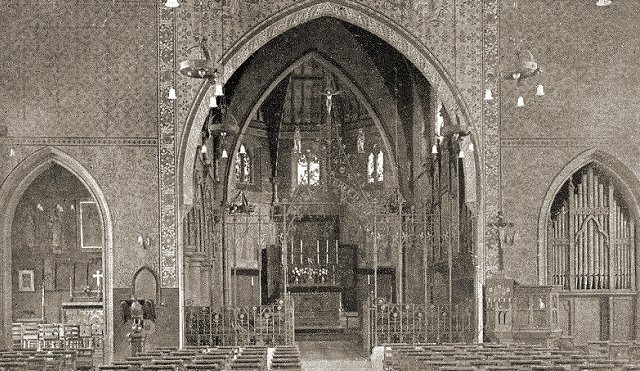

The interior of St. James' Church.

From an old postcard.

In 1855 John Nock Bagnall, one of

the church wardens, became the church’s patron. The

first minister, Joseph

Hall was soon followed by William Graham Cole who took over

on 5th September, 1846. Two years later cholera spread through the town and

claimed 200 victims, more than half of whom lived in the

parish. Cole and his assistant curate bravely entered

victims’ houses when the other occupants had fled,

leaving the victim to die. In 1853 Cole was joined by

assistant curate Richard Twigg who would eventually

become the most influential minister at the church.

Twigg was born in Yorkshire in 1825

and ordained in 1850. He came to Wednesbury after

serving as a curate in Northumberland. He took over

after Cole’s death in 1856 and became known for his

eloquent preaching and his mission services. Through his

efforts at least 30 young men entered the ministry and

more than 1,000 children attended Sunday school. One of

the people whose lives were greatly changed by him was

Dora Pattison, better known in Walsall as Sister Dora,

matron of the Cottage Hospital.

The interior of St. James' Church

in 1905.

Richard Twigg’s wife was equally

enthusiastic and held meetings in some of the local

cottages, which led to the formation of St. Peter’s

Mission Chapel in Meeting Street, which opened in 1872

in two converted cottages. Unfortunately she didn’t live

to see the opening as she died in 1869. Her funeral

service was attended by between 4,000 and 5,000 people,

and she was commemorated by the building of the chancel

apse. Richard Twigg died in 1882.

Other building work included the

addition of two chapels, one in 1887 as a memorial to

John Nock Bagnall, and the second, on the south side of

the chancel, as a memorial to George Silas Guy and

Henrietta Maria Guy.

Another view of the interior of St. James' Church.

From an old postcard.

|

|

St. Paul’s

Church, Wood Green

The parish church was built in 1874

of red sandstone in the Decorated style, at a cost of

£5,000 by the Elwell family who ran Wednesbury Forge.

A

spire, clock and a peal of 8 bells were added in 1888.

The church consists of a chancel, nave, aisles,

vestries, north porch and a western tower with the

spire, clock and bells.

Wood Green ecclesiastical parish

was formed on 19th March 1875.

There is a font made of Caen stone

and Irish marble in memory of Mrs. Griffiths of The

Oaks, Wednesbury, a stained east window, which is a

memorial to Edwin Richards, and a west window, presented

by Job Edwards as a memorial to Bishop Selwyn.

Other

additions include a stone reredos, erected in 1903 in

memory of Alfred Elwell, and a wrought iron screen,

erected as a memorial to the Reverend Tuthill, vicar

from 1875-1902.

When the church was built, the

Church of the Good Shepherd, a

chapel of ease at The Delves was transferred to it from

St. Bartholomew’s.

The Church of the

Good Shepherd closed in 1936 when the new ecclesiastical

district of St Gabriel Fullbrook, Walsall was created.

|

St. Paul's Church. |

The interior of St. Paul's Church in 1904.

St. Paul's Church. From an old postcard.

St. Paul's Church and Wood Green Road

in 1903. From an old postcard.

|

St. Luke’s

Church, Alma Street, Mesty

Croft

The parish of St. Luke was created

in 1944, and started with St. Luke’s Mission, founded in

1879 in a building originally owned by the Elwell

family, and used as a school for the children of their

workers. In 1884 the building was enlarged and a chancel

added. The church in its final form opened in 1894 and

survived until the 1970s.

St.

Andrew’s Mission Church, Kings Hill |

| The church, built in 1893 to 94,

was built at a cost around £1,700.

In 1903 a small two-manual organ was

added, and paid for by public subscription.

In the same

year the day schools in connection with the church were

enlarged and restored at a cost of £850. |

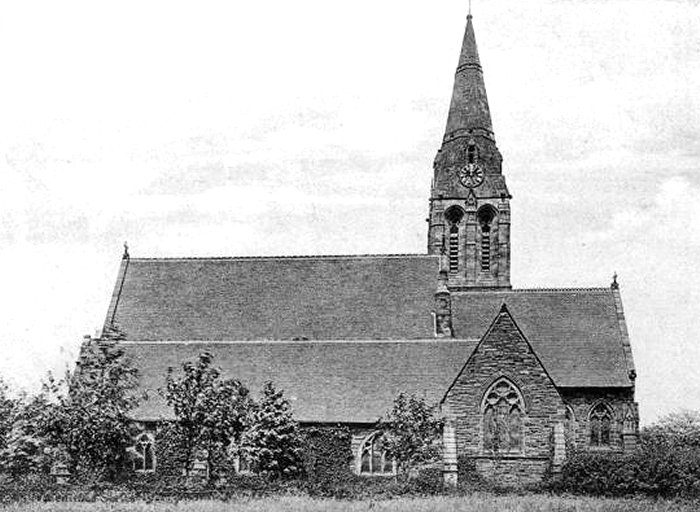

St. Andrew's Church. |

|

A side view of the church from

Kings Hill Park. |

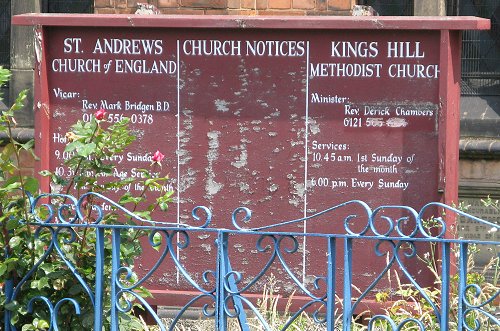

| The church also became Kings Hill Methodist

Church, as can be seen from the notice board opposite. After many years of dereliction, and proposed

demolition, the church will be converted into a

residential property.

|

|

|

The stained glass windows and

memorial plaque from the church are now on permanent

display at Darlaston Town Hall. |

| The stained glass windows at

their new location in Darlaston Town Hall. |

|

|

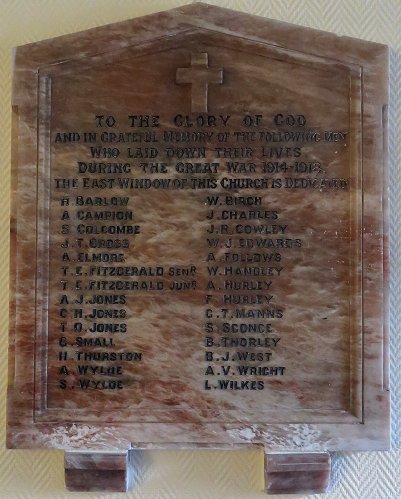

The Great War memorial plaque

from St. Andrew's Church.

As seen at Darlaston Town Hall in

2014. |

| The Reverend George Montgomery formed a Roman

Catholic mission at Wednesbury in 1852 and soon had

upwards of 3,000 members. A church was quickly required

and land for the purpose was purchased by Father Crewe

of the Bilston mission.

A small church and the existing

presbytery were soon built, after much opposition from

the Protestants, who talked of destroying it by

purchasing and working the underlying minerals.

|

|

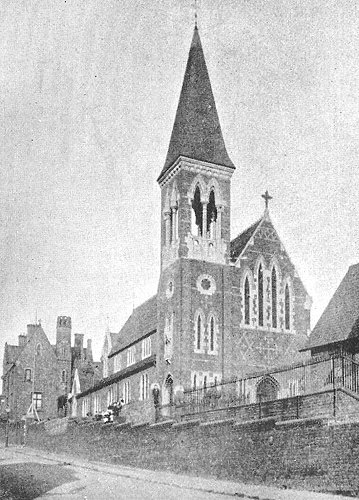

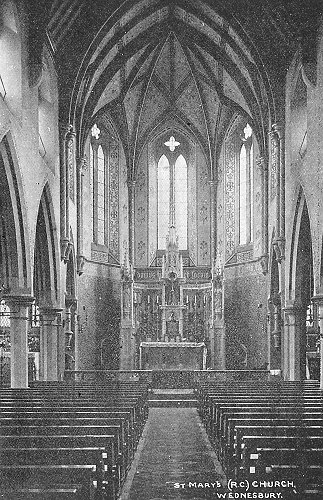

From an old postcard. |

|

St. Mary's Church. |

| Montgomery’s successor Stewart Bathurst found the

original chapel in a bad state of repair and also had

the task of providing a school due to the Education Act

of 1870. As a result he built two schools, one on Church

Hill accommodating 255 children, and another in Portway

Road, accommodating 319. The

existing church was built in 1872 to the designs of Mr.

Gilbert S. Blount of London. It is in early English

style and consists of a nave, aisles, chancel, chapels,

and towers. |

|

|

|

|

Two

views of St. Mary's Church. |

|

|

Another view of St. Mary's

Church. From an old postcard. |

|

Methodism

Wednesbury is well remembered for

the riots and anger caused during some of John Wesley’s

visits to the town. His brother Charles Wesley came in

1742 and preached at Holloway Bank, making several

converts who met regularly, and encouraged John Wesley

to come to the town to preach. His first visit took

place on Friday 7th January, 1743 and during

the evening he gave a sermon at the Market Cross

building. The following day he preached 3 times at

Holloway Bank and the number of Wesleyans in the society

reached 29. By the following Tuesday the number of

members had increased to 100.

His next visit in April was very

different due to hostility fuelled by the Parish Church

vicar, Edward Egginton. When he visited again in May the

membership had reached 300 and a march was arranged to

Walsall. During the proceedings a hostile crowd gathered

showing much opposition. By the end of the month things

went from bad to worse when rioting began on 30th

May. During the riot the windows of John Adams’ house in

Darlaston were broken.

|

| As a result Mr. Adams, and the Chief Constable of

Wednesbury, along with prominent Methodist Francis Ward,

the underground manager in John Wood’s colliery, went to

obtain a warrant from the magistrate.

The mob became more hostile and they were stoned. The

magistrate refused to issue a warrant and Francis Ward

was savagely manhandled by the crowd. |

John Wesley greets the Wednesbury

mob. |

|

Three weeks later a crowd from

Wednesbury and Darlaston assembled in Wednesbury

churchyard and proceeded to attack the houses of the

local Methodists. The damage was most extensive in

Darlaston. The disturbances continued for the next 8 or

9 months and Wesley recorded his thoughts on the matter

in his journal on 18th February, 1744:

“Ever since the 20th of

last June the mob of Walsall, Darlaston and Wednesbury,

hired for that purpose by their betters, have broken

open their poorer neighbour’s houses at their pleasure

by night and by day; extorted money from the few that

had it; took away or destroyed their victuals and goods;

beat and wounded their bodies; threatened their lives;

abused their women (some in a manner too terrible to

name) and openly declared they would destroy every

Methodist in the country – the Christian country where

His Majesty’s innocent and loyal subjects have been so

treated for eight months and are now by their wanton

persecutors publicly branded for rioters and

incendiaries.”

He briefly visited Wednesbury on

22nd

June, but did not appear publicly. His next visit

however would be very different. At midday on 20th

October, 1743 he preached from the now famous “horse

block” at the High Bullen (in reality a flight of steps

leading to the upper floor of a malt house) without

incident. He then went to Francis Ward’s cottage and

while he was there the mob arrived, but soon moved on.

He now felt it was time to leave, but was persuaded not

to do so.

By 5 o’clock the mob returned and

surrounded the cottage with cries of “Bring out the

minister!” The mob’s leader entered the cottage to see

Wesley and soon quietened down. Wesley then went out to

talk to the crowd who asked him to go with them to see

the magistrate at Bentley Hall. He consented to do so

and along with some of his colleagues and the crowd of

300 or so they proceeded to see Mr. Lane at Bentley

Hall. Mr. Lane told them to go home and be quiet, but

this was not good enough for the crowd who then escorted

Wesley to see another magistrate, Mr. Persehouse in

Walsall. Mr. Persehouse had retired for the night and so

the crowd decided to go home. At this point they were

attacked by a mob from Walsall, into whose hands Wesley

fell. His captors were very hostile and while they were

deciding what to do next, Wesley began to pray aloud.

The leader of the mob was so moved by his words that he

had a change of heart and they let Wesley and his

friends go. That night they returned to Wednesbury after

having a lucky escape.

In November violence broke out in

West Bromwich, and later in Darlaston after Vicar

Egginton’s visit. He got the town crier, Thomas Winsper

to announce that the Methodists must come to the Crown

Inn and sign a recantation or expect to have their

houses pulled down. This threat was the start of the

events that took place in Darlaston during the following

January and February. On 13th, 14th, and 23rd January a

great mob gathered in Darlaston and fell upon several

people who were going to Wednesbury and also on the wife

of John Constable of Darlaston. Constable obtained a

warrant against the offenders for criminal assault on

his wife, but only one person was arrested. When he was

brought before the magistrate, the magistrate declined

to act. As a result the mob sacked Constable’s house on

the 30th

of the month and he and his wife took refuge with a

friend. The mob then threatened the friend’s house and

so the Constables were forced to flee.

The next day a mob assembled at

Church Hill, Wednesbury but left after hearing that some

of the Methodists were preparing to defend themselves.

Wesley himself came to the town and preached the next

day without incident. He stayed until the morning of

Monday 6th February and was accompanied on

the first part of his journey by James Jones a fellow

Methodist preacher. On Jones’ return he found his fellow

Methodists in prayer, having heard that a mob would

arrive the next day from Darlaston and elsewhere

to plunder the house of every Methodist in the town.

At 8 o’clock the next morning Jones

addressed his fellow Methodists, and as he was doing so

the news came that the mob had already entered the town

and had began to break into the houses. Jones himself

went into hiding and left for Birmingham early the next

day. The mob entered each of the leading Methodist’s

houses, breaking windows and window frames, smashing

everything inside and generally wrecking the place.

Anything of value was taken away. No resistance was

offered and most people fled, only some of the children

remained, not knowing what to do.

The mob’s ring leaders threatened

to sack any of their employees who did not join them in

the riot and offered to cease rioting if the members of

the Methodist society would sign an undertaking to never

invite or receive Methodist preachers again. They did

not receive a single signature.

The next day similar outrages were

carried out at Aldridge, but this time the returning mob

was relieved of their spoils by a group of responsible

citizens who took the goods to the Town Hall and invited

the owners to come and collect them. Some of the victims

unsuccessfully attempted to obtain a warrant against the

principal rioters, but none of the local magistrates

would comply.

Wesley stated that 33 people had

suffered damage to their property with an estimated loss

of over £500. F.W. Hackwood suggests that 13 of the

victims lived in Wednesbury and that their losses

amounted to £325.16s.6d. The disturbances which were not

confined to this area where clearly well planned and

organised beforehand. Some members of the mob were

forced to participate by their employers and others may

have taken part in order to steal goods from the houses.

Things began to quiet down, and

although Wesley visited and preached in the town on

several later occasions, it all went off peacefully. On

15th

March, 1761 he preached before a crowd of between 8,000

and 10,000 people in Monway Field. The rise of Methodism

in the town greatly benefited from the increase in

population due to the industrial expansion in the area.

Meeting Street is named after the Wesleyan Chapel that

was built there in 1760 and remained in use until 1813.

|

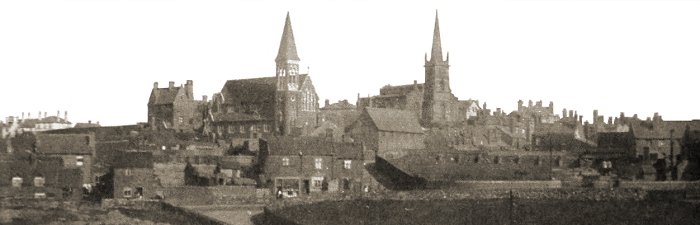

St. Mary's and St. Bartholomew's on Church

Hill.

|

Spring

Head Wesleyan Church

The church was built in 1867 on the

site of the old Methodist chapel from 1760 and could

seat about 1,100 people. In front of the church stood

the old “horse block” from the High Bullen on which

Wesley used to preach. There were also two large church

schools, originally built in 1847. They were modernised

in 1886 at a cost of about £1,500 and could accommodate

nearly 600 children. The church was rebuilt in 1932, and

demolished in 1965, only two years short of its

centenary.

Spring Head Wesleyan Church.

Spring Head Wesleyan Church

interior.

A Primitive Methodist chapel opened

in Camp Street in 1824 to accommodate 500 people,

followed by 5 others between 1850 and 1873. By the 1960s

there were 7 Methodist chapels the town:

Spring Head, Riddings Lane, Camp

Street, Elwell Street, Vicar Street,

Joynson Street, and Old Park Road.

Old Park Road Primitive Methodist Church.

Trinity

Congregational Church, Walsall Street

|

|

The later church. |

In 1761 the Congregationalists

purchased land on Holyhead Road and built a chapel which

opened in 1762.

In 1848 to 1850 they built a chapel in

Russell Street which flourished for 20 or 30 years.

By

the end of the century it was in decline, but fortunes

soon changed and attendances began to increase, so much

so that in 1904 Trinity Congregational Church was built

in Walsall Street at a cost of £4,300.

The church opened

in 1905 and could seat 600 people. |

The chapel in Russell Street.

|

Baptist

Church, Holyhead Road

The first Baptist congregation in

the town met in the old Quaker meeting house in 1834 and

then from 1838 in a chapel in Dudley Street. In 1848

they purchased the ex Congregationalist’s chapel in

Holyhead Road. Attendances dwindled and two years later

they had to leave, some members returning to the Dudley

Street chapel.

By 1856 their fortunes revived and

they returned to the chapel in Holyhead Road, now known

as Aenon Chapel.

Salvationists

The Salvation Army started in 1878

and reached Wednesbury in 1879. They began meeting in

one of the old Methodist chapels in Holyhead Road and

then in 1882 moved to the Theatre Royal in Earp’s Lane.

In 1905 they moved to Upper High Street and opened a

second barracks in Crankhall Lane.

Church Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to the

16th Century |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Early Industries |

|