|

Life

in the

19th Century

Willenhall, like other towns in the

Black Country, greatly expanded and prospered in the

19th century thanks to the growth of local industries,

which dominated the area. Large numbers of people moved

into the town to find employment, and by the end of the

century there had been a 6 fold increase in the

population.

|

Year |

Population |

|

1801 |

3,143 |

|

1811 |

3,523 |

|

1821 |

3,965 |

|

1831 |

5,834 |

|

1841 |

8,695 |

|

1851 |

11,931 |

|

1861 |

17,256 |

|

1871 |

18,146 |

|

1881 |

18,461 |

|

1891 |

16,852 |

|

1901 |

18,515 |

By 1801 most of the working population

were employed in manufacturing, as can be

seen from the following figures taken

from the 1801 census:

|

Inhabited houses |

511 |

|

Number of families in the

houses |

572 |

|

Uninhabited houses |

43 |

|

Number of males |

1822 |

|

Number of females |

1321 |

|

Number employed in

manufacturing |

1270 |

|

Number employed in

agriculture |

80 |

|

Number in other employment |

33 |

|

Population |

3,143 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

View the

entry for Willenhall in

the

Staffordshire General &

Commercial

Directory for 1818 |

|

|

View the

entry for Willenhall

in Pigot & Company’s

Staffordshire directory of

1842 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| The

town centre in the 1840s |

|

| |

|

|

|

Pigot & Company’s directory

provides us with a snapshot of life in Willenhall during the

middle of the 19th century. The town had become a centre for

metal working industries, many of which were based in small

workshops, often in a yard behind the business owner’s house,

such as the workshop in today’s Lock Keeper’s House in New Road.

The main products were locks,

keys and allied industries. The directory lists 280 lockmakers,

90 keymakers, 11 key stampers, 17 spring latch makers, 15 door

bolt makers, 2 brass founders and casters, 3 die sinkers, 5

filemakers, 5 iron and steel warehouses, and 2 varnish makers.

There was also an iron works

and colliery at Lane Head owned by local ironmaster Daniel

Bagnall. Coltham Ironworks and Colliery opened in the late 1790s

after the opening of the Wyrley and Essington Canal, and

stretched from Lane Head to Coppice Lane. The colliery no doubt

supplied the ironworks. Both the colliery and the ironworks

closed around 1850.

Local products were exported to

many parts of the world, including Europe, South America, and

the colonies. Luckily the country’s first long distance railway,

the Grand Junction Railway, had its station in the town,

followed by the Midland Railway in 1872. In 1846 the Grand

Junction Railway became part of the country’s largest rail

network, the London & North Western Railway, which ran services

throughout much of the country, and must have greatly benefited

local manufacturers. By 1855 Willenhall came to dominate the

local lock making industry. At the time there were 340 lockmakers in Willenhall, 110 in Wolverhampton, and 2 in

Bilston.

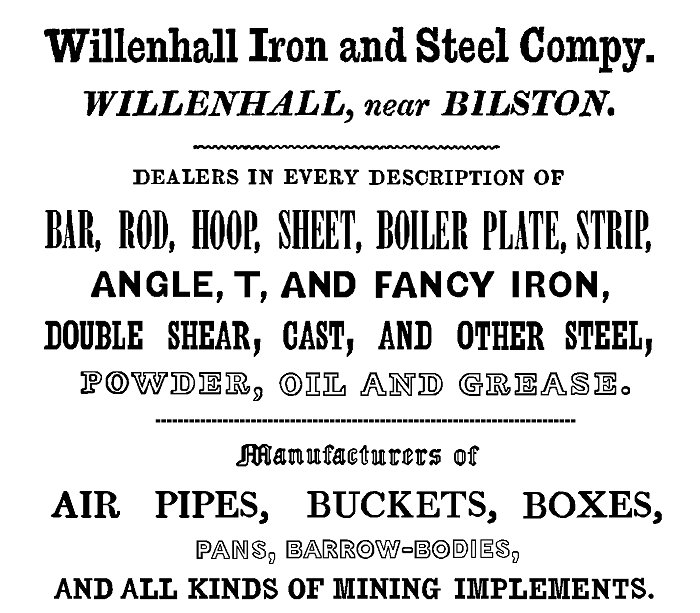

An advert from 1851.

In 1855 Willenhall Furnaces

began to operate on a site between the Bentley Canal, Sandbeds

Road, and Forge Road. The business was initially owned by Fletcher and Solly, who were later joined by Mr. Urwick, who provided extra

capital. They had three 45 ft. high blast furnaces, with a

maximum width of 13 ft. 6 inches. There were two calcining

kilns where crushed lime was burnt with the ore

before being transferred to the furnaces, and a

large coke hearth which converted coal to coke for

smelting. The blast for the three furnaces was provided by a 150 hp. condensing beam engine. The whole iron-making process soon became

more efficient when the waste gases were trapped at

the top of the furnaces and used to heat the blast

engine boilers, and later the blast itself.

The company owned several coal

mines in the area including the nearby Clothiers Colliery, which

supplied coal to the iron works via a 2 ft. 6 inch gauge

tramway, with about a mile of track. The wagons were hauled by horses until 1862, when they

were replaced by an 0-4-0 steam saddle tank locomotive, designed

and built by John Smith, at the Village Foundry in Coven. The

following year a second, more powerful 0-4-0 John Smith saddle

tank locomotive came into operation on the site. They hauled

around twenty five tons of coal each day from the nearby mines,

and coal from the nearby canal basin that came from Sneyd

Colliery, near Bloxwich, which was also owned by the firm. The

locomotives also hauled limestone and iron ore, which also

arrived by canal.

In 1872 when the Wolverhampton

and Walsall Railway opened, the company constructed a standard

gauge siding to Stafford Street Station and acquired a

second-hand standard gauge Sharpe Brothers 0-6-0 saddle tank.

The firm went public

in 1875 and became the Willenhall Furnaces Company Limited. At

the height of production around 500 tons of iron were produced each week. The

company became a victim of the depression in the iron trade, and

suffered from flooding problems in the mines. By 1881 only one

furnace was still in use. The business went into

receivership, and closed on the 9th April, 1881. |

An advert from Slater's

Classified Directory of the Manufacturing

District, 15 Miles Around Birmingham. Published

in 1851. |

|

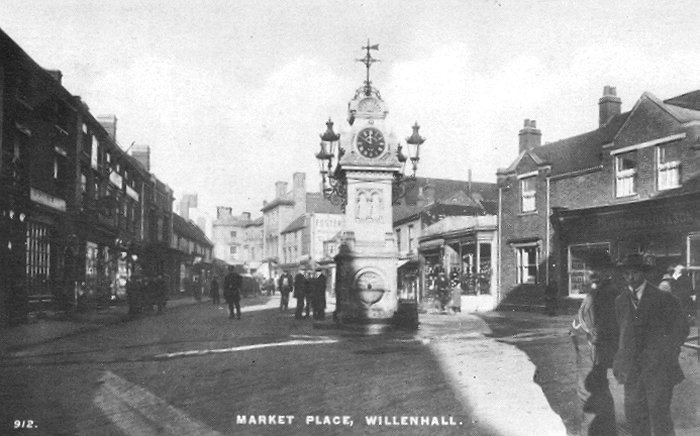

The Market Place around the

end of the First World War. |

Willenhall has had a thriving market for several

hundred years. In the 19th century the stalls were

erected below the old market cross, until a handsome

covered market was built.

Traders had to pay a rent to use the new

building, which soon closed because they preferred

to set up their stalls in the Market Place, which

was free. |

| The old market cross, as it was called,

consisted of a 2 storey building, with market stalls

on the ground floor, and a school room above. In the

18th century it was the site of the first open air

Methodist service in the town, and a site used for

bull baiting, until it was banned in 1825. Today’s elaborate market clock

was built in 1892 as a memorial to Joseph Tonks, a popular local

figure, who kept the Forge Inn in Spring Bank, and practised

medicine. The clock still has its original drinking fountain and

horse trough.

The town was well served by a

variety of shops. The directory lists 46 shops in the town

centre, although in actuality there were many more. The Market

Place was full of small shops, selling all kinds of goods and

services, so that locals could do most, if not all of their

shopping in the vicinity. In Lichfield Street was Willis

Butler’s hairdressers, and in Walsall Street stood Henry

Greader’s watch makers shop. Glass and china could be obtained

from John Harper in Wolverhampton Street, and books, stationery,

and printing were available at Charles Berry’s premises, also in

Wolverhampton Street. The chief constable, John Austin, could be

found at his bakers shop in Stafford Street, and in Church

Street there was even a steel truss maker in the form of Daniel

Read. |

| The post office

in Wolverhampton Street was run by postmaster John Tildesley. Letters from Walsall and parts east and south arrived by foot

post, every morning at eight, and were despatched every

afternoon at half past three.

Letters from Wolverhampton and

parts north and west, arrived by foot post every afternoon at

four, and were despatched every morning at half past seven. |

Wolverhampton Street in the

1920s. |

| Public Transport

People could easily travel to most parts of the

country by train, and local coaches and omnibuses

passed through the town.

Coaches called at the Neptune Inn, which was run by the Hartill

family and stood almost opposite St. Giles Church in Walsall

Street. The coach to Lichfield from Wolverhampton called at the

inn every morning except Sunday, at twenty minutes past nine. The

coach to Wolverhampton from Lichfield called at the Neptune

every afternoon except Sunday, at five p.m.

Omnibuses also called at the

Neptune. There were two omnibuses daily, except on Sundays, to

Birmingham, and two daily to Wolverhampton. There were also

omnibuses from the Three Crowns and the Queen's Arms.

Local carriers transported goods to Birmingham,

Wolverhampton, and Walsall. They included

Benjamin Smith, Wheatcroft and Company, John Shepherd, Ezekiel

Stokes, Pickford & Company, Mrs. Knowles, James Beddows, William

Fletcher, William Kendrick, and Joseph Lloyd.

Looking into Walsall Street

from outside Dale House. From an old postcard.

Public Utility Services The town was supplied with gas

by the Willenhall Gas Company, which also supplied Essington,

Hilton, and parts of Bilston, and Darlaston. The company was

formed in 1837, and an Act of Parliament for incorporation was

Passed in 1857.

The company’s agent was John Greader, based in

Church Street. The gas works was originally in Lower

Lichfield Street, but couldn’t keep up with demand. |

|

The location of the Gas

Works in Lower Lichfield Street. |

| Gas prices were initially as follows:

A single jet factory light - six pence per

week.

A double jet factory light - nine pence per

week.

A house or shop light - £2.2s.0d. per year.

A fish tail light - £2.10s.0d. per year.

A public house light - £3.3s.0d. per year. |

|

The new gas showroom and

offices. |

| In 1891 the company purchased a piece of land in

Clarkes Lane from the Hincks

family, on which to build a larger gas works. The company was one of the

first to charge for gas using British thermal units, after

obtaining an Order under the Gas Regulation Act of

1920. The company’s prices were some of the lowest

in the Midlands, with special discounts for

industrial customers. Labour saving devices were

installed at the works, which in the late 1930s carbonised around 27,000 tons

of coal a year. The company also produced around 11,000 tons of

coke annually. |

|

In 1935 a new office and

showroom was built in the Market Place, with a general stores,

fitting shops, and a cookery demonstration room. The building

opened in 1937 during the company’s centenary

celebrations.

The town was also supplied

with gas from the Mond Gas Company at Dudley Port, which

specialised in selling cheap gas to industrial users.

Electricity was supplied by the Midland Electric Corporation for

Power Distribution Limited, based at Toll End Road, Tipton. The

supply consisted of 200 volts, 2 phase, A.C. at 50Hz.

Water Supply

In 1859 water was obtained

from the Wolverhampton New Waterworks Company, founded in 1852.

In 1868 it was taken over by Wolverhampton Corporation.

Isolation Hospital

On 12th May, 1894 the Local

Board of Health decided to set up an isolation hospital to

isolate patients suffering from Small Pox which had reached

epidemic proportions in the town. Messrs. Wards

'Casting House' was acquired, and wooden buildings were added for

additional wards. Patients were transported to and from the

hospital in a horse-drawn ambulance, acquired for the purpose.

The hospital was built at a cost of £520, furnished for £300,

and had a maintenance bill of £500.

An early problem

was the cost of keeping patients at the hospital.

Initially they were each asked to pay 20 shillings a

week, which was a lot of money at the time. This was

soon withdrawn, and they were asked to pay whatever

they felt they could afford.

The hospital was

eventually taken over by the County Health

Authority, and survived until the 1920s when it

became surplus to requirements.

|

|

Neachells Lane in the early years

of the 20th century. The row of trees was known as

'Twenty Trees'. From an old postcard. |

The Old Toll House. From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Local Government |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to Religion

and Churches |

|