|

Doctor Tonks and the Memorial Clock

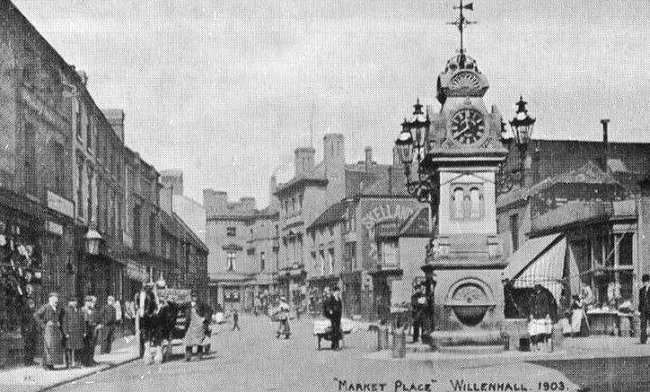

Almost everyone who has entered

Willenhall Market Place will be aware of the tall

memorial clock at the southern end, which is

dedicated to Doctor Joseph Tonks, who cared deeply

about the poorer members of society and sadly had a

relatively short life.

Joseph Tonks was born in Spring Bank,

Willenhall, on 5th May, 1855 to Silas and Lucy Tonks. Silas was a

master padlock smith and the family is believed to have moved to the

Forge Tavern in St. Anne’s Road, on the corner of Sharesacre Street,

shortly after Joseph’s birth. Silas was licensee of the pub.

In 1861, the family moved across the road to

the newly opened Spring Bank Tavern where Silas was again the

licensee. He stayed until his death in 1888 at the age of 61, when

his wife Lucy took over and ran the pub until her death in 1896. Her

daughter Emily, now married with the surname Handley, then became

licensee.

Joseph’s early education was probably at St.

Anne’s Church School in Ann Street, or the National School, that was

on the corner of Doctor’s Piece and Lower Lichfield Street. |

The memorial clock. |

| On leaving school he trained for five years

under Doctor Moses Taylor, a surgeon at Cannock

and also studied medicine at Queens College,

Birmingham, from where he graduated in 1879, to

become a member of the Royal College of

Surgeons. Now qualified, he decided to start a

medical practice in Wolverhampton Street,

Willenhall, where he stayed for about a year. In

January, 1881, local surgeon Doctor William Pitt

died at the early age of 46. Soon afterwards,

Joseph Tonks took over Doctor Pitt’s practice at

number 3 Walsall Street. In the 1881 census, it

is listed that Joseph shared the house with his

33 years old medical assistant, Richard Dudley,

together with his wife Emma Dudley, their four

children and a 14 year old servant named Harriet

Hatchaner.

On 30th, October, 1888

Joseph married 18 years old Clara Banks at St

Anne’s Church, Willenhall. She was the daughter

of Jonah Banks and his first wife Eliza

Thompson. Jonah’s firm, Jonah Banks & Sons

Limited, of London Works, Clothier Street,

Willenhall, was one of the oldest established

companies in the town, having started trading in

about 1790. The firm manufactured door bolts,

door handles and gate catches etc.

Joseph and Clara had two

sons, Reginald Ernest, born on 5th November,

1884 and Herbert Joe, born on 13th April, 1886.

|

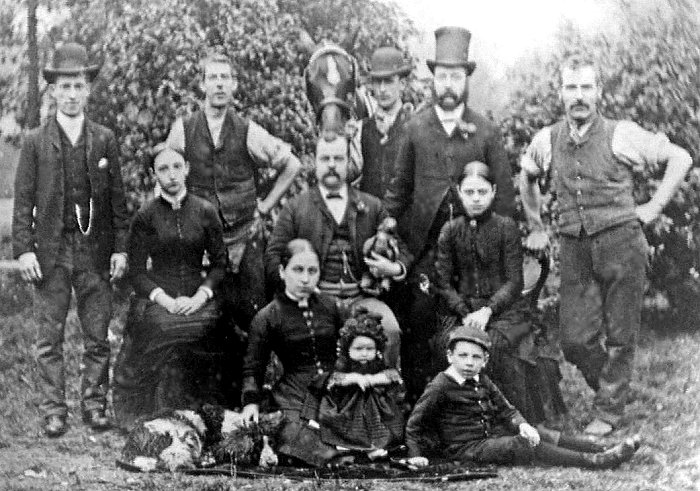

|

Doctor Tonks and his

household in 1885. Courtesy of David Parsons. |

|

Doctor Tonks worked

tirelessly to improve the health of the

poorer people in the town, where he became

known as ‘The poor man’s doctor’, charging

just six pence per visit. He was a medical

referee for the Prudential Assurance

Company, a member of several societies, as

well as the local Liberal Club, in which he

became Vice President.

It seemed that Joseph

would have a long and happy life, but things

went very wrong on Wednesday, August 29th,

1888, at the Willenhall Horticultural

Society’s annual show in the grounds of the

Central Schools, in Stafford Street. One of

the attractions was a hot air balloon ascent

in the Countess of Dudley balloon, owned by

Captain Morton of Oldbury. The balloon would

be manned by Doctor Tonks, Mr. Joseph Baker,

a local plumber and the pilot, Lieutenant

Lempriere. This was to be Joseph Tonks

second ascent in the same balloon. His first

ascent was when it

was used at the previous show, three years

earlier.

The balloon arrived at

nine o’clock and was quickly inflated. The

weather looked favourable, but at the last

minute it was decided that only two people

should make the ascent instead of three and

so Mr. Baker stepped out of the basket. As

Lieutenant Lempriere called ‘Let go’ a gust

of wind caused the balloon to rise at an

oblique angle. The balloon rose to a height

of about ten feet, followed by a descent of

a couple of feet on to the fence that

surrounded the school ground.

The balloon rapidly got

free and rose to roof height, but collided

with the chimney of Mr. John Perry’s shop at

49 Stafford Street,

causing it to fall down. The balloon then

struck both chimneys in Mr. William Wallern’s house, also causing them to fall

down. The balloon rose yet again and

collided with the chimneys of Mr. Collett’s

house and finally with the chimney of the Haden family’s house, before

being torn apart. The envelope was wrapped

around the chimney, and the basket was left

suspended by its netting, about ten feet in

front of the house.

The onlookers must have

been shocked at what they saw and worried

about the safety of the two men. Haden

family members also had a narrow escape.

Mrs. Haden was in the yard with her three

children watching the ascent. When the

chimney fell, they rushed for shelter in the

house, with Mrs. Haden carrying the youngest

child. Before they entered the house, Mrs.

Haden and the child were knocked over by a

discharge of sand from the balloon and were

only able to get to safety thanks to Mrs.

Haden’s sister, who managed to quickly drag

them into the house. It seems likely that

they would have been badly injured both by

the sand and falling bricks. It was later

discovered that the balloon had been filled

with around ten percent less gas than

normal.

The doctor managed with

difficulty to descend down one of the ropes

to safety, while the lieutenant descended by

means of a ladder. He managed to escape

unhurt, other than being badly shaken and

bruised, but the doctor had received a wound

about 2 inches long and an inch wide in the

fleshy part of the left thigh. He was also

badly bruised on his left knee and left

shoulder.

When Doctor Tonks

reached the ground, he visited the marquee

to assure everyone that he was not too badly

injured and was then taken home by a friend.

It was not realised that although the

injuries would take some time to heal, they

would result in his early and untimely

death.

Initially he seemed to

be on the road to recovery. In 1889 he

passed an examination for the Licentiate of

the Apothecaries Hall, Dublin, which enabled

him to add the letters L.A.H. to his name

and he became Medical Officer for the

Guardians of the Poor and also Public

Vaccinator for the towns of Willenhall and

Short Heath. He also continued with his

heavy workload, but his health began to

deteriorate and was a source of concern to

family and friends. The deterioration

continued, so much so that shortly after

nine o'clock on Thursday, May 2nd, 1891 he

passed away, just three days before his 36th

birthday. At the time, his widow Clara was

just 27 years old with two children to look

after. Doctor Tonks was buried 5 days later

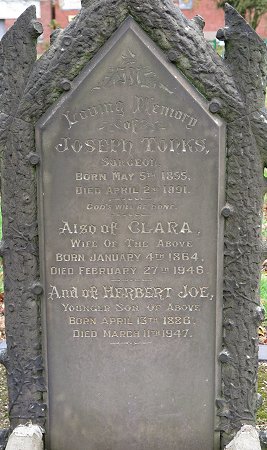

at Wood Street Cemetery, Willenhall. |

|

|

|

|

Doctor Tonks'

family grave in Wood Street Cemetery. |

|

| Clara and her children moved from

their home in Walsall Street to enable

Doctor William Bott M.R.C.S. who had

become Doctor Tonks' assistant, to take

over the practice. He is listed as a

surgeon, medical officer and public

vaccinator for the Wolverhampton Union.

Clara and the children are believed to

have moved to Harper Street, where they

lived for several years before moving to

Clothier Street. In the 1920s, Clara

and her younger son, Herbert Joe, moved

to Wolverhampton, living in Cemetery

Drive, which was between what is now

Aspen Way and Merridale Cemetery. All

that stands there today is a row of

garages. Clara died on February 27th,

1946 at the age of 82 and was buried in

the same grave as her late husband.

Herbert Joe survived her for just over a

year. He died on 11th March, 1947 at the

age of 62 and was also was buried in the

family grave. His younger brother

Reginald Ernest Tonks, died in 1962.

The

Memorial Clock

Many local people

were saddened and shocked at the loss of

their doctor, who in his short lifetime

had done so much to help the residents

of the town. As a result a meeting was

held in the New Inn, Walsall Street, now

called The County. A memorial committee

was formed and the landlord agreed to

make a room available for future

meetings.

The committee

decided to raise money to erect a

drinking fountain in memory of Doctor

Tonks. Mrs. Tonks readily gave her

support to the plan and many generous

donations were quickly received. Money

poured-in and it was realised that

something far grander than a drinking

fountain could be built.

Willenhall

Local Board of Health was contacted to

ask permission for a drinking fountain

to be erected in a prominent place.

Meanwhile a design was drawn-up for a

drinking trough for cattle and dogs,

with four clock faces, by Messrs Boddis,

sculptors and stonemasons of Birmingham.

It was to be built in Hollington and

Bath stone with a clock supplied by

Messrs Smith of Derby, surmounted by an

ornamental frame. The total estimated

cost was £250.

The Local Board of

Health recommended that the memorial

should be built in the Market Place, the

supply of water for the drinking trough

being supplied by Wolverhampton

Corporation. Work on clearing part of

the southern end of the Market Place in

readiness for the building of the

memorial, began in April 1888 and

building work rapidly progressed. It was

decided that the day of the inauguration

of the memorial should be a general

holiday. |

|

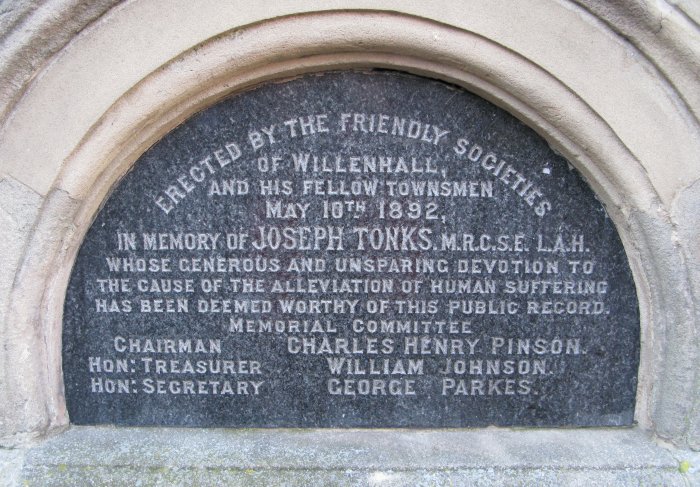

Some of the

dignitaries at the unveiling ceremony. |

The unveiling ceremony

took place at 4 o'clock in the afternoon on

Tuesday 10th May, 1892. It was a bright

sunny day and large crowds gathered in the

Market Place and along the route to be taken

by the procession.

Many shops and

factories closed and a large number of flags

and banners were flown. The long procession

started from Stringes Lane at about 3

o’clock and included members of the local

and school boards and members of local

friendly societies. The procession also

included ‘D Company’ of

the 3rd Volunteer Battalion, South

Staffordshire Regiment, the Fire Brigade and

military prize bands.

A platform had been

erected in the Market Place to accommodate

the Memorial Committee, town dignitaries and

guests. Mr. James Carpenter Tildesley,

ex-Chairman of the Willenhall Local Board of

Health presided at the event.

The memorial was

unveiled by the surgeon Lawson Tait.

Afterwards there was an official banquet

with yet more speeches. The day was a great

success, everything went as planned.

|

|

The plaque on the memorial clock. |

|

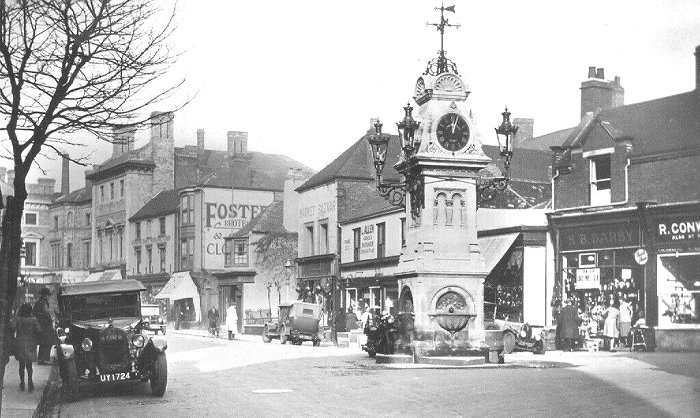

Another view of the

memorial clock. |

|

On the first anniversary of

the unveiling, Wednesday 10th May, 1893, a

dinner was given to celebrate the successful

event. On 31st July, 1986 the memorial was Grade

II listed. It is still one of the best known

structures in the town. |

|

The memorial clock in

the late 1920s. From an old postcard. |

|

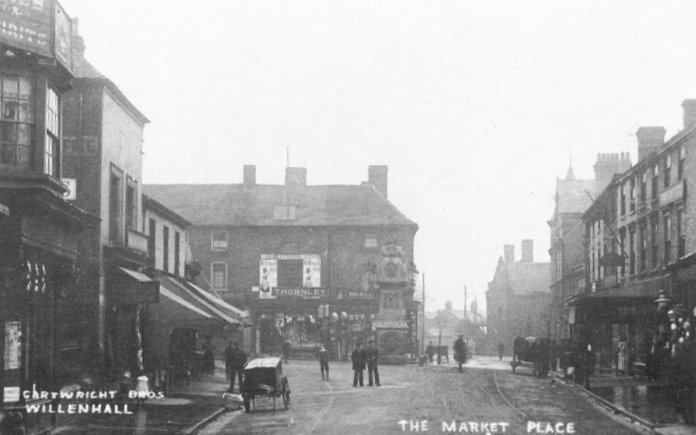

A late

1920s view of Walsall Street. |

|

An earlier

view of Walsall Street, looking

towards New Road. |

|

The Midland Bank and

Market Place. |

| By the late 19th century, Willenhall’s

graveyards were rapidly running out of space, and a new cemetery

became a necessity. It was decided to build a cemetery on farm land

in Wolverhampton Road West, Bentley, acquired from the Earl of

Lichfield in 1894.

The new cemetery was designed by the town

surveyor, Mr. B. Baker, who planned the site to include a mortuary

chapel, and a sexton’s lodge. |

|

The cemetery entrance. From an old postcard. |

|

Work started on the site in July 1896, and was

carried out by Mr. Owens of Wolverhampton. During the following

year the site had been prepared, and drainage work undertaken. The

chapel, lodge, and walls were constructed by Mr. Thomas Tildesley,

who began working at the site in July, 1897.

The new cemetery was officially opened by

Thomas Nicholls J. P., Chairman of Willenhall Urban District Council,

on the 16th July, 1900, in front of a crowd of around 2,000

spectators. The final cost of the project was £7,725.12s.0d.

Somewhat more than had been previously expected.

|

From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

|

The Boer War

Many Willenhall men joined the army, and fought

in the Boer War in South Africa between 1899 and 1902. Twenty three

of them lost their lives. They joined the following regiments: the

South Staffordshire Regiment, the Shropshire Light Infantry, the

Worcestershire Regiment, the Imperial Yeomanry, the North

Staffordshire Regiment, and the East Kent Regiment. They are

recorded on two plaques at the back of Willenhall War Memorial.

|

The bonfire built to celebrate the Coronation of King

George V and Queen Mary, on the 22nd June, 1911.

|

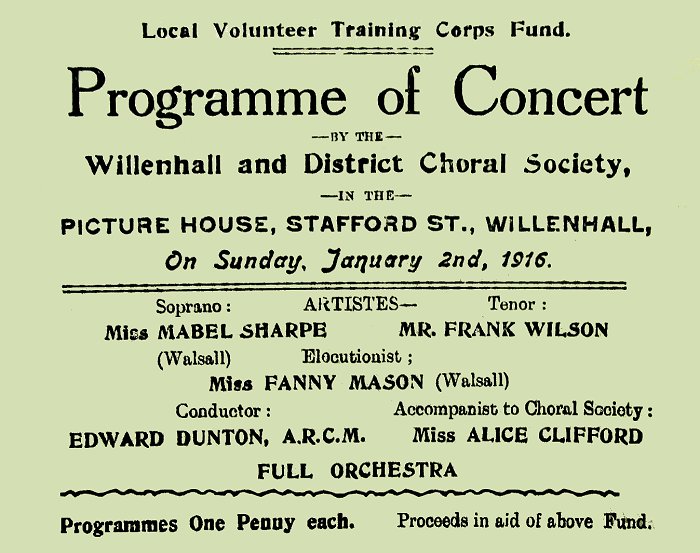

Willenhall Choral Society. From an old

postcard.

Spring Bank Stadium

The stadium, which was built on the north side

of Temple Road, opened on Monday 4th September, 1905 with a match

between Birmingham (now Birmingham City) and the Willenhall Swifts.

It was watched by a large crowd who saw Birmingham win by 3 goals to

1. The ground became the headquarters of the Swifts and continued to

be so until the First World War. The last match before the war

intervened, took place on the 30th October, 1915 between the Swifts

and their local rivals, the Willenhall Pickwicks. After the war the

two teams amalgamated to form Willenhall Football Club, with Spring

Bank Stadium as their headquarters. The new club played its first

game on the 26th April, 1919 at Walsall, with a return match at

Spring Bank the following week. The team played in the Birmingham

and District League and won the league championship in 1922.

By 1930 the number of spectators had

drastically fallen, and the club found itself in financial trouble.

The club went into voluntary liquidation, and Spring Bank Stadium

was sold and converted into a greyhound track. Greyhound racing

continued on the site until 1980 when the owners, Ladbrokes decided

to close the stadium because of falling attendances. It was sold to

Barratts, who demolished the stadium and built around 100 houses on

the site. It is commemorated in the names of a couple of the streets

that were built on the site; Stadium Close, and Circuit Close.

Willenhall’s present football team, Willenhall

Town was formed in 1953 and plays at its site in Noose Lane.

|

|

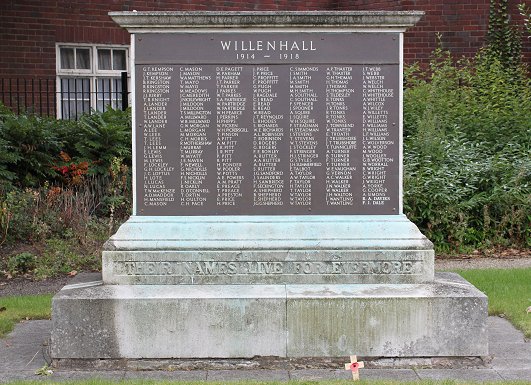

The First World War

When war was declared on 4th August, 1914 large

numbers of Willenhall men joined the local regiments and soon found

themselves fighting abroad, in France, Belgium, and as far afield as

the Dardanelles.

Many of them lost their lives during the fearsome

fighting in the trenches at the Somme, and at Ypres, Paschendaele,

and the Gallipoli Campaign.

They are remembered thanks to the war memorials

at Portobello and Willenhall. 312 names are recorded on the

Portobello war memorial, and 445 names are recorded on the

Willenhall memorial.

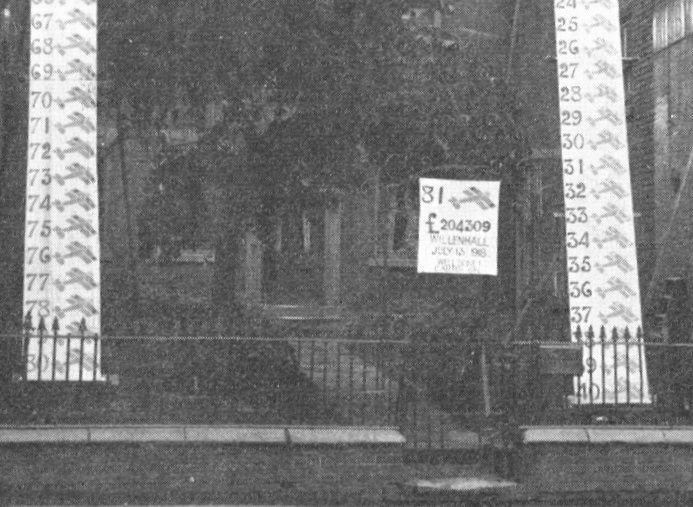

The people of Willenhall are well known for

their generosity. During the war they collected £204,309 for the war

effort.

As the war progressed, local manufacturers received

orders for war work from the Ministry of Munitions, and produced

many items including gun parts, shells, hand grenades, and horse

shoes. |

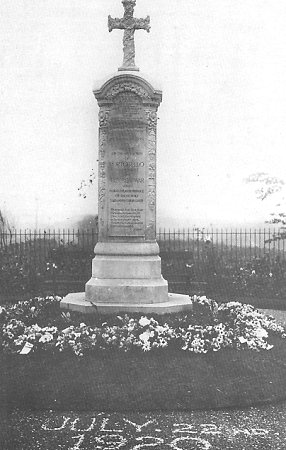

| The

Portobello war memorial. From an old

postcard. |

|

A photo from an old

postcard celebrating the collection of

£204,309 during Willenhall War Weapons Week.

Enough to buy 81 aircraft. |

|

An old postcard

showing some of the celebrations in the

Market Place at the end of the First World

War. |

|

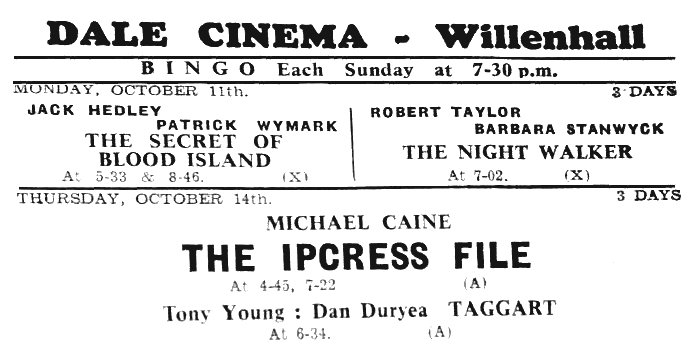

Cinemas

Willenhall's first cinema, the Coliseum, opened

in 1914 in the old Hincks family’s malthouse on the corner of

Bilston Street and New Road. This was soon followed by the opening

of a second cinema, the Picture House, which opened in Stafford

Street on the 19th April, 1915. The Picture House was a

purpose-built cinema with first class facilities, whereas the

Coliseum was housed in a not very suitable building, with inferior

facilities. The Picture House was the more successful of

the two, particularly when ‘the talkies’ arrived.

From an old postcard.

Another view of the Picture House. From an old

postcard.

When Mrs Price, the last member of the Hincks

family, died, her estate, including the Coliseum was put up for

sale. It was purchased by John Tyler, a local councillor, builder,

plumber, and decorator, who with his daughter Norah, decided to

replace the cinema with a modern state of the art design.

|

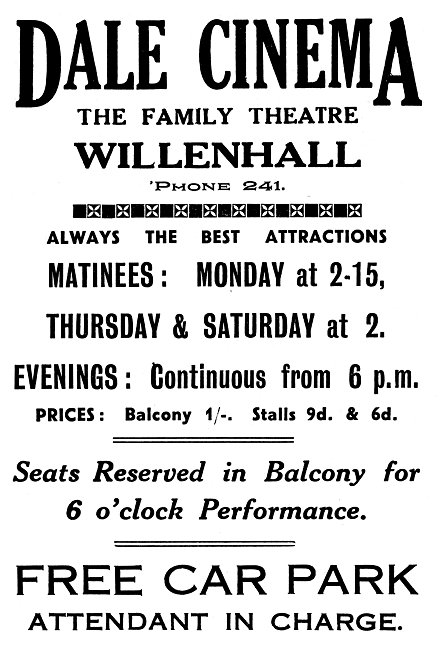

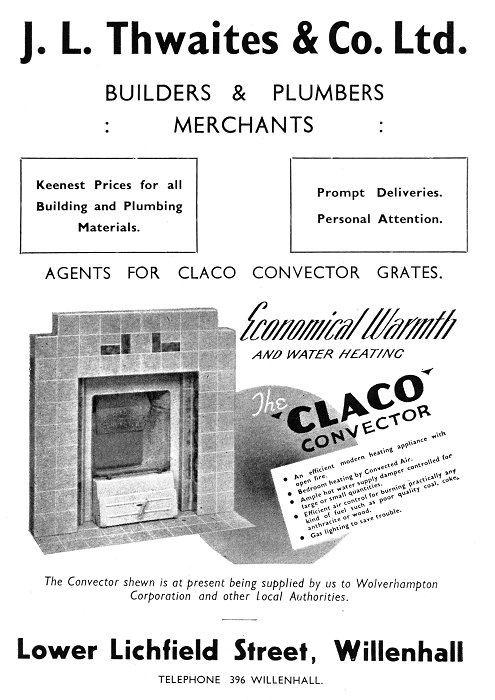

An advert from 1937. |

The building became the Dale Cinema, seating 1,150

people, including 250 on the balcony. It opened on the

31st October, 1932 with a showing of ‘Viennese Nights’,

in Technicolor, with high quality Western Electric

sound. Norah Tyler continued to run the cinema until her

death in 1945 when it was acquired by J. L. and A. H.

Brain who ran a cinema at Aldridge. With the increased popularity of television,

cinema audiences started to dwindle, and Willenhall, like many other

towns eventually lost its cinemas.

The Picture House closed on the

2nd May, 1959 and was demolished in 1961. The Dale continued in

operation until the 30th December, 1967, then reopened as a bingo

hall on the 16th February, 1968.

In the late 1990s it was converted

into a public house, appropriately named ‘The Malthouse’,

a J. D. Wetherspoon’s pub, which opened on the 21st December, 1999.

It began to suffer from a lack of customers and so was

put-up for sale. It finally closed its doors on Sunday

the 26th March, 2023. |

|

|

The Dale Cinema in the 1930s.

Courtesy of John Hughes. |

|

An advert from 1965. |

| |

|

| View the Willenhall entry

in the Midland Counties of England Trades Directory of

1918 |

|

|

| |

|

|

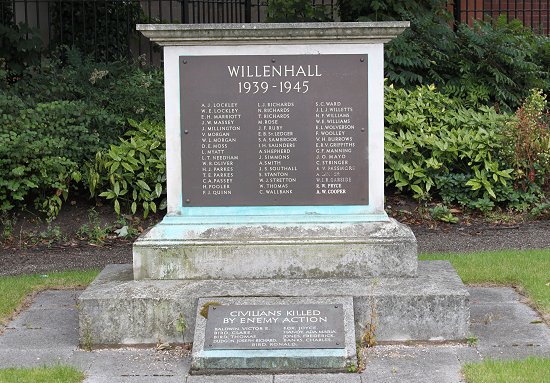

The Willenhall War Memorial. |

Willenhall’s War Memorial on the corner of

Stafford Street and Field Street was officially opened on the 30th

September, 1920 by Lord Dartmouth.

The memorials were dedicated by

the Reverend H. P. Hyatt on the 4th June, 1922.

There are two plaques commemorating those who died in

the First World War, and a large and small plaque

commemorating those who died in the Second World War.

Two other plaques set in the boundary wall

commemorate those who died in the Boer War. In between

them is a small plaque stating that the tablets were

moved to the war memorial in 1964 having been removed

from the gate piers at Wood Street Cemetery. |

One of two plaques dedicated to those who

died in action in World War One.

The memorial for those who died in World War

2.

|

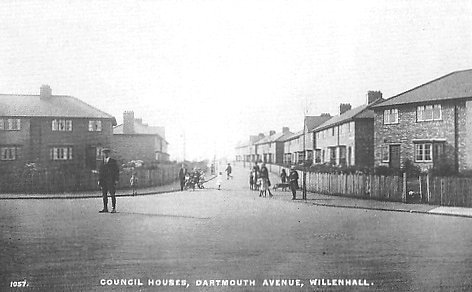

Municipal Housing

The local population steadily increased during

the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century, so that

new houses were badly needed to reduce overcrowding, and to improve

living standards amongst the poorer members of society. The

council’s Housing and Town Planning Committee held its first meeting

in November 1918 and considered the possibility of buying land for

new housing.

The 1919 Housing Act gave local

authorities the responsibility to provide suitable

housing for the expanding working class population.

|

| In August 1919 the council purchased land in

Temple Road for the building of 74 council houses, which were to be

the first council houses in the town. Over the next few decades, thousands of council

houses were built throughout the town, and much of the open land

disappeared.

The houses were built in many areas including Spring

Bank, Wolverhampton Road, the southern side of the Memorial Park,

and the area to the east of Rose Hill. |

From an old postcard. |

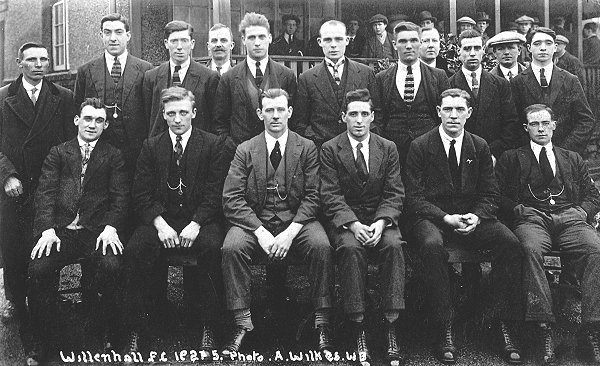

Willenhall Football Club. Date unknown.

Courtesy of Tony Highfield.

|

In 1931 Willenhall lost its passenger train

services at Stafford Street railway station when the LMS withdrew

passenger services on the old Midland line. The railway remained

open for goods until the 1st November, 1965.

An advert from 1937.

An advert from 1937.

|

World War 2

Although fewer lives were lost during the

Second World War, its impact was just as great as the previous

conflict. In September 1940 the council launched an appeal called

‘The Willenhall Fighter Aircraft Fund’. It raised £6,750 to pay for

a Spitfire aircraft which was presented to the government on behalf

of the local people, and named ‘Willenhall’.

A few weeks later

Willenhall directly experienced the might of the German Luftwaffe

during the town’s first air raid. On the 20th November, houses were

destroyed in Ward Street, Ann Street, and Springvale Street, and St.

Anne’s Church was slightly damaged. 12 people were killed, and many

were injured, or left homeless. The homeless were initially cared

for by the Salvation Army at the Citadel in Moat Street.

Those killed were: Clara Bird, Ronald K. Bird,

Thomas Bird, Joyce Fox, Frederick Jones, Lily Jones, Mary Jones,

William Moreton Jones, Joseph Lockley, Geoffrey Morris, George

Morris, and Owen Morris.

There was a second air raid on 31st July, 1942,

this time on the Wolverhampton to Walsall Road. It seems that German

aircraft were following the railway line, and dropped bombs en

route. Four people were killed, and several houses and part of a

factory were destroyed.

Those killed were Beatrice Farrington in

Peel Street, Ada Maria Handy in New Road, Joseph Richard Dudgon in

Wolverhampton Road, and Charles Henry Banks, also in

Wolverhampton Road. The civilian dead from the air raids were buried in a special

part of Bentley Cemetery. |

An advert from 1937. |

|

|

An advert from 1926. |

During both air raids the enemy aircraft were

fired on by the anti-aircraft guns that were set up on an area of

land between Ashmore Lake and Broad Lane South, known as the Five

Fields. There were several large guns, searchlights, and radar which

were manned by members of the Anti Aircraft Regiment. The site was

totally unsuitable, being heavily waterlogged in the winter months,

and so the battery only stayed for part of the war.

During the air raids, help was provided by the

100 or so volunteers in the Willenhall section of the Women’s

Voluntary Service, and the town’s Civil Defence Services. The

Willenhall Fire Service also helped out in the aftermath of air

raids at Birmingham, Coventry, Liverpool, London, Manchester, and

Plymouth.

Willenhall war memorial contains a plaque

listing 93 names of members of the armed forces who were killed by

enemy action during the war. Although the number is far less than in

World War One, it still had a huge impact on the town.

|

|

The Post War Years

After the war, Willenhall continued as a busy,

successful industrial town, much like its neighbours.

In May 1948, the houses in St. Ann's Square, which stood

on the southern side of Ann Street, at the eastern end,

past St. Anne's Church, were declared to be unfit for

habitation and a demolition order was served on them.

They were home for 50 to 60 people who then had to find

alternative accommodation. The site was acquired by H.

G. Smith, Steel Fabrications.

St. Ann's Square. From an old

newspaper cutting. |

|

|

View the Willenhall

listing from

a 1961-62 Trades Directory |

|

| |

|

|

In January

1965 the town lost Bilston Street railway station when the line was

closed to passenger traffic.

An even more important event happened

the following year as a result of the Local Government Reform Act.

Despite much local opposition, Willenhall lost its status as an

urban district, and like neighbouring Darlaston, and Bentley, came

under the direct control of Walsall Metropolitan Borough.

|

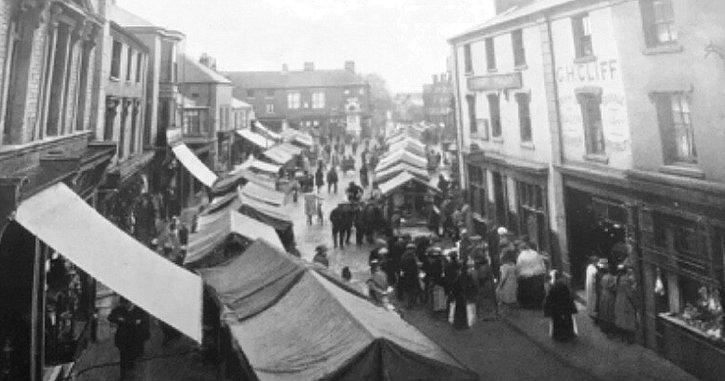

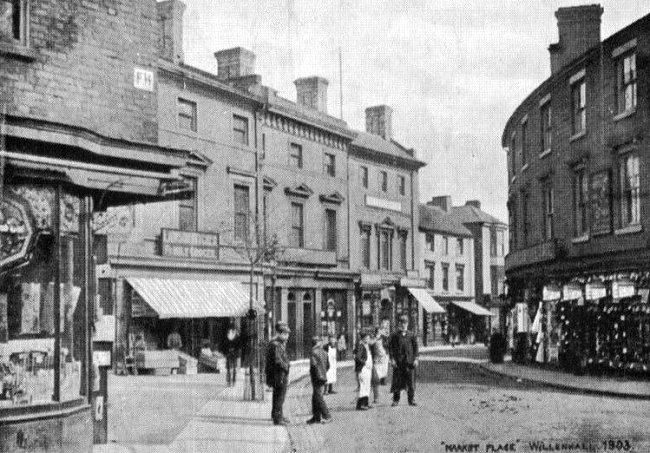

The Market Place. |

| By the late 1970s, Willenhall, and the other

Black Country towns were beginning to feel the effects of industrial

decline. Job losses were reported almost daily in the media, and

many once successful businesses closed. The factories started to

disappear, and many of the larger factories such as John Harpers,

Josiah Parkes, and even Yale’s Wood Street factory, have now gone,

something that was unimaginable only a few decades ago. Lock

manufacturing in Willenhall has almost disappeared, only a

handful of skilled lockmakers now remain in business. Luckily the industry is still remembered in the

form of the Locksmith’s House, in New Road. It opened in April 1987

as The Lock Museum, and has displays featuring locally made locks,

one of the few remaining lock workshops, and an early 20th century

lock maker’s home. The museum suffered from insufficient funding and

closed in 2002, but luckily the Black Country Living Museum took the

site over, and after a lot of investment, reopened it in 2003 as The

Locksmith’s House. It is the country’s only dedicated lock museum. |

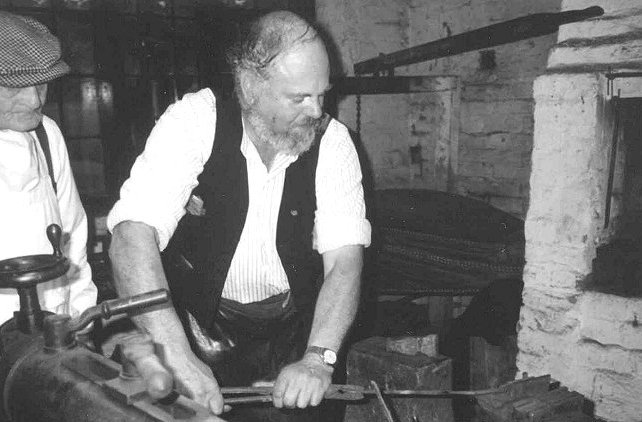

Tom Millington and David Plant demonstrating

at The Lock Museum.

An evening view of the memorial

clock in the Market Place. Taken by Richard Ashmore in

the mid 1970s. |

|

Another view of the memorial

clock, taken by Richard Ashmore in the mid 1970s. |

The old Post Office in

Wolverhampton Street, now a chemist. Taken by Richard

Ashmore in the mid 1970s. |

Sorting the Christmas mail at the

post office. Richard Ashmore who took the previous three

photographs is on the far right looking down. |

|

A Willenhall messenger boy,

from an old postcard.

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

Walsall Street in the 1920s. |

|

A view of St. Giles' Church from

Walsall Street, taken by Richard Ashmore in the mid

1970s. |

|

An advert from 1948. |

The largest development in the town centre took

place in 2009 with the demolition of Yale’s Wood Street factory, and

the building of the new Morrisons store, which opened in January

2010.

Although many changes have taken place over the

last few years, Willenhall is still regarded as one of the most

intact towns in the Black Country, still retaining much of its

original atmosphere.

Many little workshops and factories remain

around the town, giving a flavour of the once successful

manufacturing centre.

Many of the lovely Georgian and Victorian

buildings still survive, and the vibrant Market Place has kept much

of its character.

|

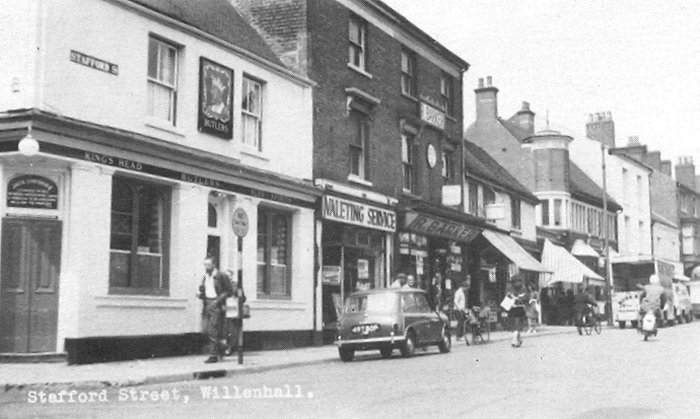

|

Stafford Street in the 1970s. From

an old postcard. |

|

The Market Place in the

1970s. From an old postcard. |

|

An earlier view of Stafford

Street before the modern shops were built. |

From an old postcard.

Some of the lovely old buildings that are to

be found in the Market Place.

| Much of the town centre is now designated as a

conservation area, and so its character and charm will survive. Many

Willenhall people are fiercely independent, and although the

town is now part of Walsall, it still retains its own identity, and

hopefully will continue to do so, and continue to prosper, for years

to come.

The Town Crier, Cyril

Richardson, in 2010. The 81 year old began his career as

a town crier in the early 1990s, and has been doing it

in Walsall since the mid 1990s. |

|

| On a sad note,

part of the old Legge factory shown above,

was severely damaged at the end of February

2011 after a mindless arson attack. |

|

The Market Place at night. November 2013.

|

Another night time view of the

Market Place. |

| The market in April 2014. |

|

Another view of Willenhall market in April

2014.

The Bell in 2015.

| The Old Toll House at 40 Walsall Street was

wonderful restaurant offering a first class service. It

became extremely popular and could cope with 120 diners

at a time. Unfortunately things started to go wrong

during Covid and the business never really recovered. It

began to loose money and so it finally closed on the

24th February 2025. This was a great loss because

restaurants of this quality are few and far between in

Willenhall. |

From an old postcard.

Willenhall's well known memorial clock

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Pubs |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

References |

|