|

The Workhouse

Under the terms of the Poor Law Act of 1601,

each parish was responsible for its own poor, and the distribution

of poor relief, which was funded by the poor rate. This was levied

on property owners and tenants. Often poor people would move into a

more generous parish in order to obtain a larger amount of poor

relief. This ended in 1662 with the passing of the Settlement Act,

after which only established residents (through birth, marriage, or

apprenticeship) were entitled to poor relief. Under the terms of the

Act, strangers entering a parish could be removed after 40 days, if

they were unemployed. In 1697 the Settlement Act was amended so that

anyone could be barred from entering a parish unless they produced a settlement certificate.

Life was certainly hard for the unemployed.

Many of the larger parishes opened workhouses for the poor, where

they could receive food and shelter in return for work of some kind.

On 8th April, 1741 land was acquired behind the houses on

the east side of Stafford Street for the building of the town’s

workhouse. The trustees were Dr. Richard Wilkes; John Wilkes, a

surgeon; Joseph Molineux, a maltster; Thomas Marston, a maltster;

Joseph Hincks, a yeoman; Isaac Turner, a maltster; Joshua Dodds, a

chapman; and Samuel Hawkesford, a chapman.

Little is known about the workhouse, only the

name of the last workhouse master is known. He was job Thatcher. The

entrance was in Little Wood Street. Many such workhouses were built

throughout the country, although a large number disappeared after the

passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. This created a Poor

Law Commission to oversee the national operation of the system,

which included the joining of some of the small parishes to form

Poor Law Unions, each of which had its own workhouse. As a result of

the Act, Willenhall was then administered by the Board of Guardians

for the Wolverhampton Union of parishes. The poor of the town were

sent to the Union Workhouse in Wolverhampton. Willenhall’s

workhouse closed in 1839, and the building was put-up for sale. For

many years Upper Lichfield Street continued to be known as Workhouse

Lane.

Cholera

In the early part of the 19th century, towns

and cities rapidly grew, as people flocked there to find work in the

many factories and industries that appeared at the time. The

population of Willenhall, like the other towns in the area was

rapidly increasing:

|

Year |

Population |

| 1801 |

3,143 |

| 1811 |

3,523 |

| 1821 |

3,965 |

| 1831 |

5,834 |

| 1841 |

8,695 |

This resulted in numerous problems including

cramped and unsanitary living conditions. Serious health problems

often arose from contaminated food, and an unclean and inadequate

water supply that came from wells or pumps, which would often be

polluted with sewage. This led to a variety of illnesses and

diseases, the most virulent of which was Asiatic Cholera. The

disease spread from India via trade routes, and reached Europe in

1826, spreading from Turkey to Russia, Poland, Germany and the

Baltic ports, from where it came to Sunderland in 1831. In January

1832 it arrived in Newcastle and Gateshead and soon reached York,

Leeds, Manchester, the Black Country, and London. By the autumn it

had spread to Devon and Cornwall.

Large numbers of people died as a

result of several cholera epidemics, which occurred in

1831 to 32; 1848 to 49; 1853 to 54; and 1865 to 66. The

disease first appeared locally at Bilston on 4th August,

1832 and resulted in 745 deaths, almost one in twenty of

the population.

|

|

Public Health and Housing

in Willenhall in 1841. J. Biddle,

Surgeon.

Besides the

numerous dirt heaps, small pools, and

doorway slushes fronting or adjoining

the dwellings and workshops, there are

in the town of Willenhall two vast

masses of stagnant filth and

putrescence, sufficient to breed a

plague throughout the whole of England.

Mr. Biddle,

surgeon, who has resided 20 or 30 years

in the town, conducted me to one of

these enormous accumulations, which

runs, or rather creeps along a field,

partly under a hedge, at the bottom of

the churchyard. At my particular

request, Mr. Biddle made a special

examination of this and the other mass

of filth, and communicated the result to

me in writing, to which I beg to call

your attention.

Sir,

Willenhall, near Wolverhampton, April

12th. 1841.

I have looked over

the filthy accumulations of mud which

you and I talked about: the one place

you saw with me, you know is very bad;

it extends at least from 200 to 300

yards, and contains many scores of tons

of putrid filth. This runs all along the

southern side of the town, and indeed we

may say in the very heart of the town.

On the western and north western side

there is as much, or more, filthy

stagnant accumulations of the same kind,

amounting, I have no doubt, to some

hundred tons. We may well have typhus,

etc. which we have now, and have had for

a long time, more or less.

I remain, etc.

R. H. Horne's Report in

the Children's Employment Commission

(1843)

What must be the

condition of these masses in the hot

weather, and what effect they may then

have upon the senses, I cannot pretend

to say; but on my visit, during a cool

day in April (the 4th), to the one at

the bottom of the churchyard, the stench

was most revolting. The appearance it

presented to the eye, in some places,

was that of a livid, tawney putrescence.

As I looked at it I could not help

thinking I saw it crawl. But its general

appearance was that of a dead settlement

of a dark spotty hue, not a scum, but

evidently a deep substance. It seemed a

reservoir of leprosy and plague.

Mr. Biddle

subsequently told me that "in summer it

was quite intolerable to pass the place.

There were enough marsh exhalations from

it to fill a whole country with fever."

There are but few

good houses in the town. By the term

good, I do not mean large and

commodious, but use the word in the

English sense of comfortable. The

majority of the houses are very

indifferent, and nearly all those

inhabited by the working classes are of

a squalid description, often presenting

the last state of want and wretchedness.

There are many narrow passages, as in

Wolverhampton, averaging from 21 feet to

31 feet wide. They lead into little

courts and yards, where dwellings and

workshops are always found.

Some of the houses

in the main street have an interval of

about 2 feet between them, the whole

length of which is used as a sewer for

all manner of filth, but without any

grating or means for it to be carried

off. There are many straggling lanes,

leading up hill and down hill, with

hovels and workshops at irregular

intervals. Here and there you pass

through a tortuous lane, which should

rather be called a gut, being only 2 or

3 feet wide, enclosed between broken

walls, rising over mounds of

half-hardened dirt and refuse, sinking

towards declivities of mud and slush,

and leading to other dwellings and

workshops, some on the declivities and

some on the small level, these latter

having puddles and pools of stagnant

water and filth accumulated in front of

their doors and windows. There are no

other means for the admission of air

into these abodes but from the doors and

windows in front, as they have none at

the back. There is no under-ground

drainage to any of these places; and

very seldom, indeed, have they any

privies. |

|

|

St. Giles' Church and graveyard. |

Neighbouring Willenhall had an extremely

lucky escape, with 42 cases, and 8 deaths. Although there were no

deaths in Wednesfield, Willenhall’s other neighbours didn’t do so

well. There were 68 deaths in Darlaston, 85 in Walsall, and 193 in

Wolverhampton. Thankfully by the end of 1832 the epidemic had ended.

The disease returned to the country in 1848 and again lasted

for around two years. This time there twice as many deaths,

including 292 in Willenhall.

Willenhall had escaped lightly in

1832, but little was done to try and improve the

unsanitary living conditions until 1842 when a Public

Health Committee was formed in the town. Although the

committee consisted of prominent townspeople,

they had no statutory powers to enforce any decisions that were

made.

This was not really possible until the passing of the

Government’s Artisans Dwelling Act of 1875 which gave local

authorities the power to demolish slum properties. In reality little

was achieved other than the purchase of 2 tons of lime, and two

dozen whitewash brushes, which were deposited in various parts of the

town so that the poor could at least keep their premises clean.

|

|

During the second epidemic in 1848 to 1849 the

disease appeared at Moseley Hole and spread rapidly throughout the

town, aided by warm, dry weather. The committee immediately

attempted to deal with the matter, but it was too little, too late.

Mr. Thomas Phillips was appointed for two weeks as the sanitary

inspector, at a salary of one pound a week. Two workmen were

employed to whitewash any dirty houses, and a further three tons of

lime, six threepenny bottles of Collins deodorising powder from

Whites of Bilston, and four one and threepenny bottles of Dr.

Macann's Mixture were purchased and made available for use in the

town.

The disease spread so quickly that the town’s

two doctors, Mr. J. Hartill, and Mr. J. Froysell, and the Rev. G. H.

Fisher of St. Giles’ Church laboured night and day to care for the

town’s sick and dying. They were soon joined by Dr. Pardey who was

sent by the government to assist them. The local coffin makers were

working flat out to try and keep-up with the demand for

coffins, which was so great that many of the dead were buried

without one. A hearse and horse were hired to assist with the

burials, and John Shepherd was appointed as driver, at a salary of £2

a week. Many of the wealthier people sent their families away to

places of safety. |

|

St. Giles’ graveyard where the burials were

taking place was full and so another graveyard was urgently needed.

On 6th September the matter was discussed at a Vestry meeting, but

as the estimated cost of the land, drainage, and fencing amounted to

£600, which would be paid for by levying a rate of 9 pence in the

pound, it was turned down.

The situation was critical, and so the

churchwardens made use of a piece of derelict land belonging to the

Chapel of Ease Estate. The land, situated at the bottom of Doctor’s

Piece became known as the Cholera Burial Ground.

On some days there were as many as 15 deaths

and so the bodies would hastily be buried in deep pits or trenches,

many without coffins.

The disease raged until late September, and

rapidly disappeared, only one new case being reported on the 2nd

October.

The last death from the disease took place on 4th October.

During the 49 days of the epidemic, 292 lives

were lost.

|

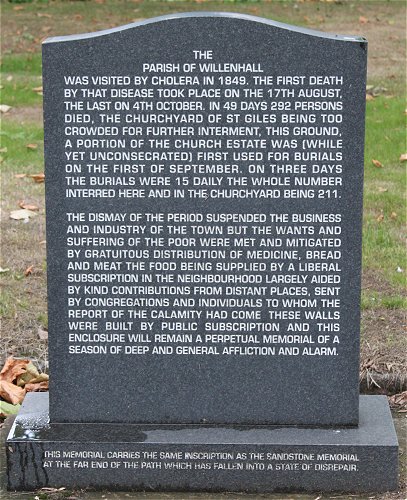

The memorial in the Cholera Burial

Ground. |

|

Part of the Cholera Burial Ground. |

Wolverhampton businessman and local benefactor,

Henry Rogers, was one of the founders of the Royal Hospital, and the

Royal Orphanage in Wolverhampton, and Holy Trinity Church and the almshouses at Heath Town.

He greatly contributed to the welfare of the cholera sufferers by

raising between £400 and £500 for the Cholera Relief Fund. |

|

Although the epidemic was over, much still had

to be done to improve the unsanitary living conditions in the town.

The Public Health Act of 1848 gave powers for the setting-up of

public health boards, which led to the formation of the Willenhall

Local Board of Health in 1854. The Willenhall Water Company was

formed in 1852 to provide a clean water supply for the town. Sadly

this took a long time to achieve. The company found itself in

difficulties and was taken over in 1868 by the Wolverhampton New

Water Company, which was later taken over by Wolverhampton

Corporation.

The disease did return to Willenhall during the

1853 to 1854 epidemic, but this time people were prepared, and

stringent measures were taken to prevent the spread of

the disease. Details of cases and deaths are not known.

It is thought that there were up to 300 cases, which

must have resulted in a number of

fatalities. Willenhall seems to have escaped the final epidemic in

1865 to 1866 when there were no recorded cases in the town.

The Cholera Burial Ground was eventually

enclosed, and consecrated on 18th July, 1867. It now serves as

a memorial garden, a reminder of one of the most difficult periods in

the town’s history.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Canals, Roads, and Railways |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Coal Mining |

|