|

The Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Technical College

was built on the site of the old Deanery in Wulfruna

Street, which was acquired from the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners

in 1912, at a cost of £6,000.

There had been a lot of opposition to the proposed

development because of the Deanery's historical

significance. But the building of the technical college

became a priority due to the lack of technical education

for the large number of people who worked in many of the

local industries.

In 1914 an

agreement was made between Wolverhampton Council and

Staffordshire County Council regarding the cost of the

new college. Two thirds of the cost would be borne by

Wolverhampton and one third by Staffordshire. The new

college would then be open to students from both areas.

A joint technical school sub-committee was set up with

ten representatives from Wolverhampton and five from

Staffordshire. It was decided that commerce and science

departments were to be included and that there would be

places for 1,100 students.

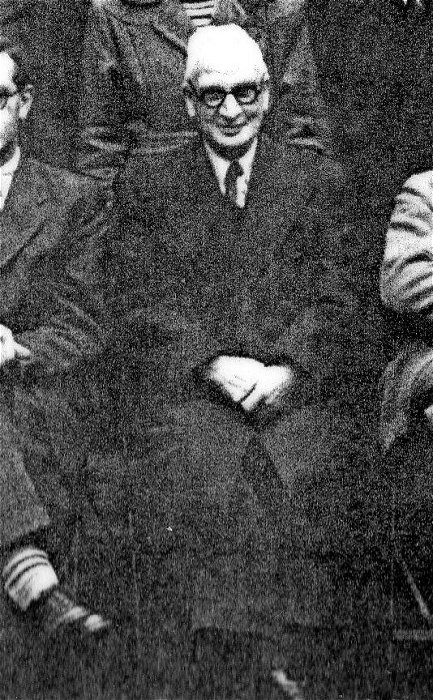

On the 5th

December, 1919, Dr. W. E. Fisher was appointed as

principal of the new college. He had previously been

Head of Engineering

at Wednesbury Technical College. He took up his new

position, early in 1920 and served as principal for

thirty one and a half years, initially helping to

push-through the plans for the new buildings.

Development of the one and a half acre site began when

the First World War had ended. In July 1922, J. March

obtained a tender to demolish the old deanery. A year

later Henry Willcock & Company Limited accepted a tender

to build the new Engineering and Technical Block at a

cost of £40,000. The final cost of the building

and equipment came to £38,900. Local engineering firms

generously provided around £3,000 worth of equipment.

The

building was opened on the 21st May, 1926 by Princess Mary Viscountess

Lascelles, daughter of King George V. It had laboratory

and workshop facilities for 665 students. In 1930 / 1931

around 1,600 people enrolled for courses in the three

departments housed in the new building. They were

Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Chemistry and

Metallurgy, and Engineering Production. |

|

The first part of the new college,

as seen from Wulfruna Street. |

| The entry in the 1930

Wolverhampton Red Book and Directory: |

|

After the initial success of the new college, thoughts

turned to expansion.

In 1930, several adjacent sites were acquired at a cost

of £5,000, and work began on what was then described as

the final portion of the college, to be built in

Wulfruna Street at a cost of £120,000.

On the 7th October, 1931, Prince George laid the

foundation stone for the new main building that was designed by Colonel G. C. Lowbridge,

architect of the Staffordshire Education Committee.

It was

built by Wolverhampton builder, Fleeming & Sons and

consisted of a steel framework encased in concrete with

a floor area of 33,350 square feet.

The new building opened in 1932,

and was later officially opened by Lord Irwin, President

of the Board of Education,

on 30th June, 1933. |

|

The ceremony of

the laying of the foundation stone on

the 7th October, 1931. |

|

The foundation

stone. |

|

The building during

construction. Courtesy of David Parsons. |

The college could now accommodate

between 1,750 and 1,900 students and for the first time

there was room for technical, commercial and domestic

science classes under one roof. In 1932 / 1933 there

were 1,507 enrolments, which increased to 2,013 in the

following year.

The entrance, known as ‘The Marble’

is named after its Botticino marble facing, 7ft. 6

inches high. It has a fine

staircase with a wrought iron balustrade, brass handrails,

a stained glass window and a glass half dome at the top. Much of the

panelling from the ‘Oak Room’ in the old Deanery was

saved, and installed in the ‘Board Room’ off ‘The

Marble’.

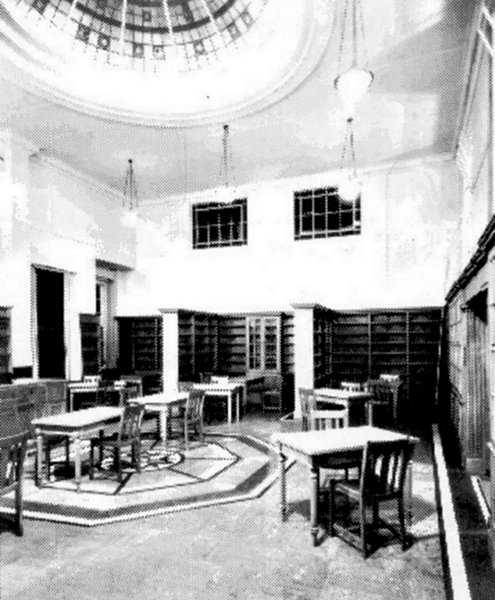

The top of the stairs

from 'The Marble', as seen in the early

1970s. Off to the right was the library,

which later became the 'Council Chamber'. |

Cross ventilation was provided in

all teaching rooms and the main staircases and upper

floor corridors had glass roofs for adequate lighting.

Vacuum points were included on all floors for cleaning

purposes. The sweepings were drawn into a receptacle in

the basement. The was also an electrically operated

goods and services lift to all floors.

In 1933, the Wolverhampton Local

Authority annual report stated that:

"The college makes ample provision

for the general education of young men and women not

privileged to obtain their higher education by residence

at a University. Particularly it is the local home of

higher scientific and industrial studies."

The buildings included a library,

an assembly hall, a gymnasium, a students' common room,

a refectory, a wide range of laboratories, teaching

rooms, staff rooms and administrative offices.

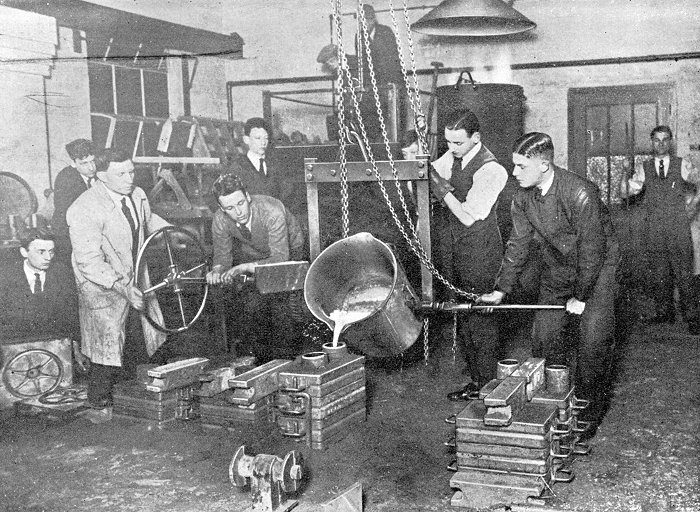

There were departments of chemistry

and metallurgy, mechanical and electrical engineering,

engineering production, building, commerce and a women’s department with courses including physical

culture, elocution, and languages.

By 1939 there were 2,921 students,

58 full time, the others part time.

One third of the students were women. |

|

The original library, now

the Council Room. It

could seat around 18 students.

Courtesy of David Parsons. |

|

An early photo of the frontage in

Wulfruna Street. |

| The entry in the 1936

Wolverhampton Red Book and Directory: |

Casting in the college foundry.

|

By the

late 1930s the governors were greatly concerned

about the lack of accommodation, as student

numbers rapidly grew. On the 25th January, 1938

proposals were made for a new development in

Stafford Street with a floor area of 8,375 square

feet, but nothing would be done for some years,

largely because of the onset of war.

In the

1930s around ten students each year were obtaining

engineering degrees at London University and so

plans were made to have a graduate students

association at the college, where research work could

be carried out.

At the

beginning of the war, classes were cancelled until

air raid shelters could be provided. When the

college reopened there was an expected fall in the

number of students, but it was not as bad as

expected. Student numbers fell to just over 1,700

which included a rise in the number of engineering

students to 653.

|

| An

agreement was made between the college and the Chief

Inspector of Armaments for around a dozen

engineering students to help the war effort by

making a number of items including gauges for

aircraft construction. John Ellson, lecturer in

Electronic Engineering and an ex-marine engineer,

oversaw the project, which continued until the end

of 1943. Some

members of staff were actively involved in the war

effort. Mr. M. Schofield, a lecturer in the

chemistry department was a gas identification

officer for Sedgley. He had to identify any gas used

in air raids. Other staff members were air raid

wardens who were not expected to attend the college

when on duty.

Service classes were run to assist the war effort.

They included: food education, the training of army

tradesmen, training of women supervisors,

instruction of tool room trainees, wireless

mechanics' courses (Wolverhampton was one of three

provincial centres selected), Ministry of Labour

courses for foremen and forewomen, ATS clerical

instruction, WAAF cook-butchers' courses, intensive

engineering courses for RAF non-commissioned

officers, fuel economy, statistical control and

quality. Also a course for REME engineering cadets, a

personal management course and a course covering modern production

techniques. In June 1944 there were 50 air crew

trainees. War work accounted for roughly half of the

work in the college. |

Dr. W. E. Fisher, College Principal. Courtesy of David

Parsons. |

| 1945

saw the formation of the Music Department,

which was unique among technical colleges. The

governors took advice from Sir Malcom Sargent and

appointed Dr. Percy Young as head of department. At

the beginning there were 135 students. A string

orchestra was quickly formed, followed by other

orchestras and choirs. There was a comprehensive

library of music, a wide range of courses and the

opportunity to take the examinations of the Royal

School of Music. In 1946 a successful

compulsory purchase order enabled the future

development of the site alongside Stafford Street

|

| |

|

| View the

college's first students' union magazine |

|

| |

|

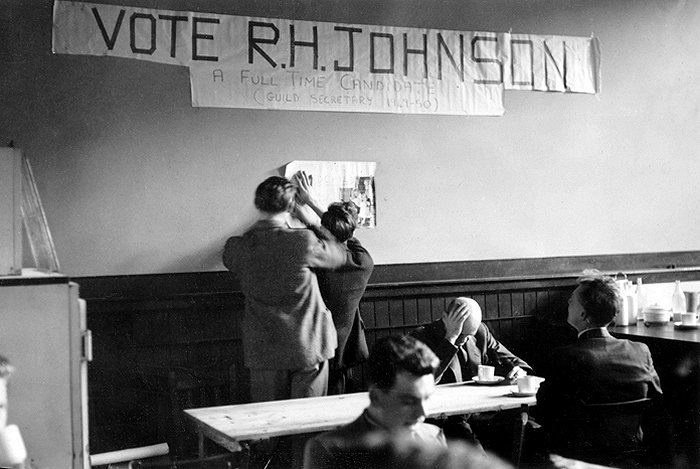

Posters for the Student

Guild election in 1950. Hung on the wall of the

Refreshment Room, built in 1948. Courtesy of

David Clare. |

|

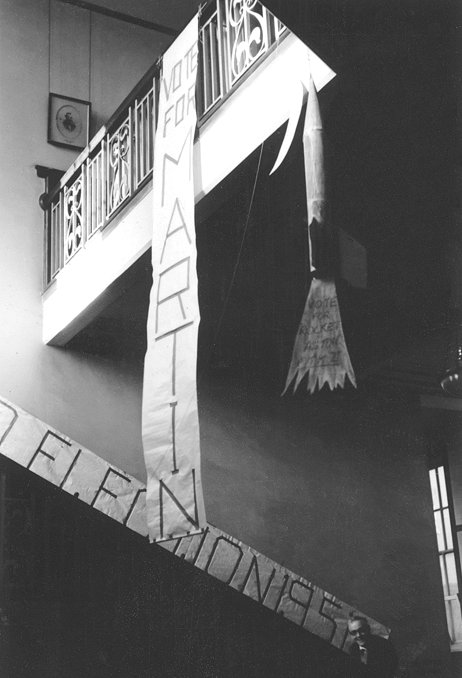

Posters for the

Student Guild election in 1951. Hung on one

of the staircases.

Cortesy of David Clare. |

|

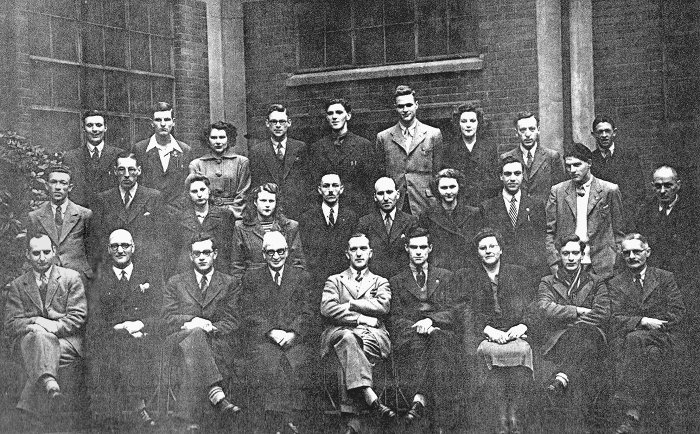

The

Students and Teachers Union Council,

1947 to 1948

Back row, left to right: W.

B. Fellows, E. Waldron, Miss

S. M. Wilkes, F. C. Bate, F.

Morrison, F. H. Anderson,

Miss M. Cooper, J. Williams,

?

Middle row, left to right:

N. Barnett, D. Roberts, Miss

S. Waldron, Miss J. Nichols,

B. Thomas, J. W. Pool, Miss

P. Whistance, ? D. H.

Westwood, ?

Front row, left to right: E.

Wells, F. Gobourn (Hon.

Treasurer), J. C. Bennett

(Asst. Hon. Sec.), Dr. W. E.

Fisher, A. S. Jordan

(Chairman), A. J. Locke

(Hon. Sec.), Mrs. M. Fownes,

J. Grieve, ?

Courtesy of David Parsons. |

|

The

drama section was becoming very popular after a

weekend drama course in November 1948 that led to

the drama group taking part in local festivals

and producing plays. The domestic classes were also

proving popular. In 1948 there were classes in

cookery, soft furnishings and dressmaking. Other

women's classes included hygiene, gymnastics,

dancing, tailoring and operatic training.

In

1948 / 1949 there were 4,650 students and

a new refreshment room was built. In 1951,

Dr. W. E.

Fisher who had been College Principal since 1920

retired. He was replaced by Mr. Charles Leslie-Old. |

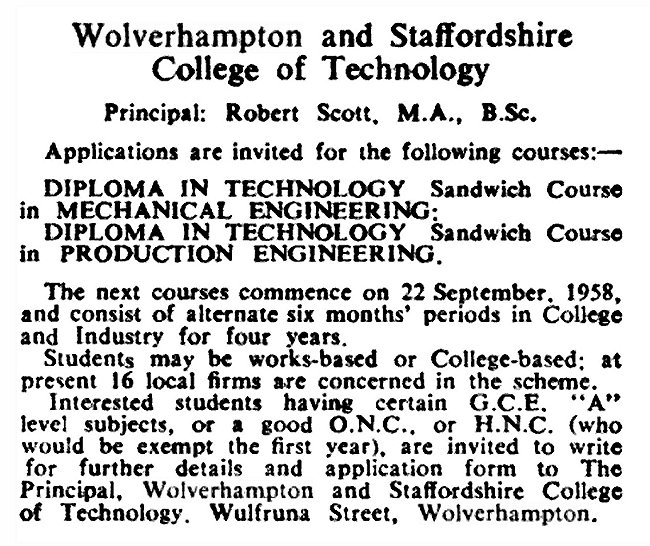

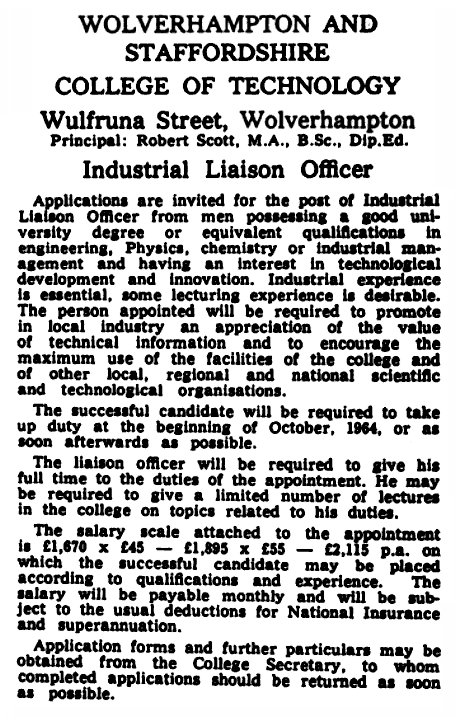

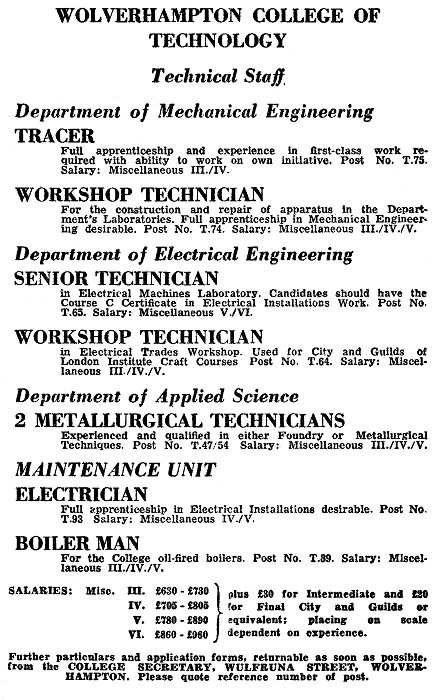

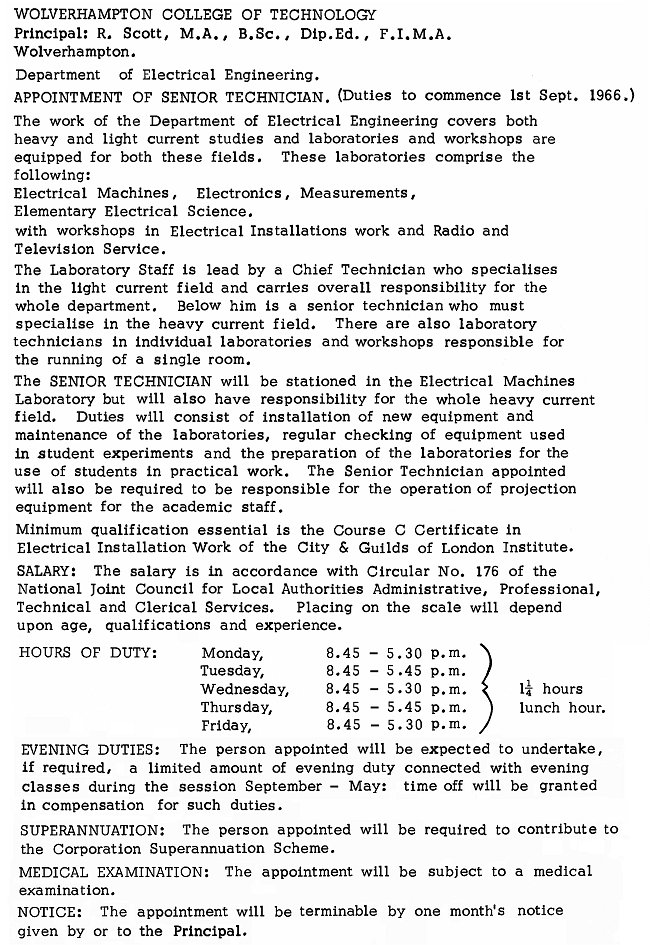

A Wolverhampton and Staffordshire

Technical College badge.

Adverts from the 1950s and 1960s

for courses or jobs:

An advert from June 1958.

An advert from June 1964.

An advert from June 1966. Courtesy of

David Parsons.

An advert from June 1966. Courtesy of

David Parsons.

The college in the 1950s.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

The Early Years |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Foundry College |

|