|

The

Hinckes Family

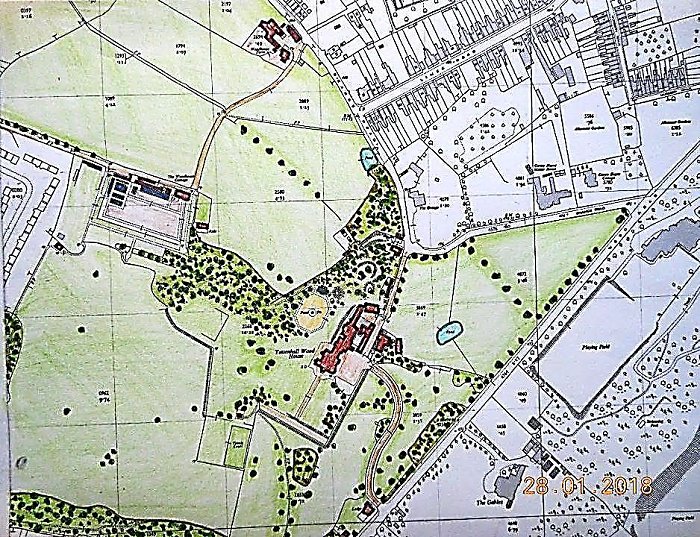

Site Plan. The area of the

rectangle is approximately 90 acres.

The Wood House, built between 1833

and 1836, appears to have occupied part of the building

plot of the earlier house, which might suggest that some

of the older structure was incorporated into the newer

one, most likely the cellars only but this is not

evident from available plans. The age and appearance of

the earlier house are not known but its outline and some

garden detail can be seen on the Tettenhall Wood Common

enclosure survey of 1809 (see in the biographical

details section).

It was this earlier house that was

purchased by Peter Titchbourne Hinckes, at some time

before his death in1781 (he also owned Bushbury Hall and

was a member of the well-known Wolverhampton family of

that name). On his death he bequeathed the house and

land to his nephew Peter Tichbourne Hinckes 1753-1822

who in turn left it to his nephew and namesake Peter

Tichbourne Hinckes son of the Rev’d. Josiah Hinckes

Tragically his nephew died only

eight days after his uncle and followed him into the

same grave at Bushbury church: the estate then

automatically passed to the nephew’s father Josiah

Hinckes, brother of the legator. It was at this point it

must have become evident that the house would eventually

pass to the older of Josiah’s two daughters, Theodosia

Hinckes. Hereto Theodosia, a spinster, would have

expected to lead a very quiet life, probably caring for

her parents in their old age and eventually retiring to

a small property, possibly in Surrey where her father

had his parish: but now her prospects were considerably

enhanced and she obviously intended to make the most of

them.

Following her father’s death in

1830 and subsequently her mother’s in 1832, Theodosia

began to realise the plans that she must have been

formulating prior to their deaths, and she may have been

responsible for some of the land acquisitions mentioned

above. It begins to become evident that Theodosia was a

cultured lady with some artistic talent; informed

architectural appreciation; considerable determination

and obviously substantial funds. First she demolished

the old house and then with the additional land,

assembled her new estate.

Entrance Front: photograph: early

20th.Century?

Her proposals give the impression

that she intended to create a small model,

self-sufficient country estate on the edge of Tettenhall

village complete with the usual country estate

components, including a small home farm; walled gardens;

greenhouses; estate lodge; tree belts; rides etc. It is

difficult for us at this distance in time from the

event, to realise how innovatory this would have been in

the Tettenhall area.

Theodosia was also a moderately

accomplished amateur water colourist who, with her sister

Rebecca, ten years her junior, spent considerable time

painting watercolours of local churches that are now in

the Lichfield Cathedral Library. These confirm her

interest in and appreciation of mediaeval Gothic

architecture and in turn the Gothic Revival style.

Gothic Revival of course was not a new style, having

first appeared about eighty years before Theodosia

thought about building her house, but it had only

recently undergone a significant renaissance and rationalisation as

a result of the work of the architect Thomas Rickman.

Rickman had unlocked the secrets of the development of

mediaeval Gothic architecture and his subsequent book,

‘An Attempt To Discriminate The Styles Of Architecture

In England From The Conquest To The Reformation’

published in 1817, proved to be a very popular

publication and became the ‘Architect’s Bible’ for the

rest of the nineteenth century, going through seven

editions.

Any architect not owning a copy of

Rickman’s book, ran the risk of his buildings looking

untutored in the eyes of informed architectural

practitioners and critics. The book was also popular

with the educated public, so it is quite likely that

Theodosia owned a copy.

When she decided to build her new

house it would have been natural for Theodosia to opt

for Gothic Revival, rather than the also recently

introduced ‘Italianate’ and ‘Greek Revival’ Styles used

by Colonel Thorneycroft twenty years later when building

his house, Tettenhall Towers, on the other side of Wood

Road. She wanted the most experienced architect

available, who would work in this new refined gothic and

make it as authentic as possible, so it is no surprise

that she approached Thomas Rickman himself - she was not

going to use any second-best practitioner. By this time

Rickman had one of the busiest practices in the country

and had moved his main office from Liverpool to

Birmingham, so he was ideally placed to act for her. She

began talking to him in 1832, the year of her mother’s

death and commenced building the following year, but

neither of them could have foreseen the fraught

relationship that would arise before the building was

completed: a very busy architect with a wealthy but hard

headed business woman for a client.

Rear of house with croquet lawn,

circa 1930s.

Having identified and named four

consecutive style developments within the historical

progress of Gothic architecture, Rickman generally

favoured his third one – ‘English Decorated: 1300-1380’

- that he used for most of his Gothic Revival buildings:

so it would have been consistent for him to use this

style for Theodosia’s new house. Not only a new style

but an asymmetrical design to boot: ‘symmetry’ had held

sway for the previous 350 years but ‘asymmetry’,

probably seen as somewhat quirky, had slowly become

acceptable as being suitable for the new gothic fashion,

following its introduction in the 1750’s. Without doubt

Theodosia was going to build a showpiece unlike anything

else that had been erected in the immediate West

Midlands area up to that date. Her house would be the

first of the range of large new houses that would

eventually define Tettenhall as the area of choice for

the wealthiest industrialists in the region; not that

Theodosia would have wished to be known as an

industrialist: the 1851 census return describes her as a

‘Landed Proprietor’. Theodosia’s relatives had been

resident in Tettenhall for some years before the later

‘newcomers’ began to arrive on this elevated sandstone

escarpment to avoid the smoke their factories were

creating in and around Wolverhampton, to the east.

The new house was built between

1833 -36 and about this time Thomas Rickman was also

involved in many other projects including the New Court

of St. John’s College, Cambridge with its famous ‘Bridge

of Sighs’ (whose window tracery resembled some of that

at Tettenhall); repairs to Canterbury; Blackburn and

Worcester Cathedrals and numerous churches and houses

from the south of England up to Scotland. He had

tremendous capacity for work, including travelling

widely to supervise the work on site, but he also relied

quite heavily on his partner Henry Hutchinson.

Hutchinson caught tuberculosis and died in November 1831

placing additional strain on Rickman: consequently after

a few years his robust health also began to fade.

Matters came to a head whilst he was building Tettenhall

Wood House and he began to suffer several seizures and

falls during his travels, which led to problems when the

cost of the house escalated well beyond its fixed budget

price. Up to this point Rickman had earned a reputation

for keeping his buildings well within budget, aided by

his early financial expertise. Theodosia blamed him for

the cost overrun and refused to pay him, even taking a

legal option on his home in Birmingham, which he was

forced to sell to meet his financial obligations, when

he retired through ill health in 1838. He died three

years later in 1841 in straightened financial

circumstances: a sad end for a man who had done so much

for the quality of early 19th.century architecture and

for the enlightenment of his architectural colleagues.

Thomas Rickman’s diaries in the

RIBA Library provide some tantalising entries relating

to Tettenhall Wood House. On the 24th.January 1833 he

‘sent off the estimate of cost to Miss Hinckes which I

fear will frighten her’. On the 20th.February he meets

Theodosia hoping to finalise the plans. On the

23rd.February he mentions that he has made many designs

for Miss Hinckes and on the 4th.March he does more

sketches for her: she appears to be making many

alterations to the plans, but on the 29th.March she

decides not to alter the drawings again. It is notable

that at many of their meetings Rebecca Hinckes and her

husband are also present.

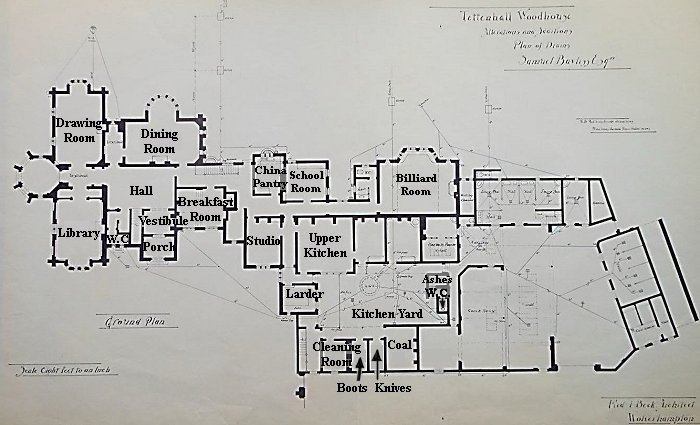

Ground Floor Plan.

Rickman refers to visiting a

brickyard in Wolverhampton on 2nd.April 1833 but the

bricks for the house may have been fired on site, a

quite common procedure at the time if suitable clay

deposits were present (see below). The stonework with

which the whole building was faced was something of a

mystery: the external walls used a hard fine grained

sandstone from an unknown source, but the carved

stonework for the window and door frames and other

details, used a fine grained oolitic limestone that

would be easier to carve than the sandstone. It is most

likely that it came from the quarries at Bath and would

have been conveyed by water, the only practical method

until the advent of the railways: in this instance it

would almost certainly have been via the Avon and Severn

rivers to Stourport and then by the Staffordshire and

Worcestershire Canal to Compton or Newbridge,

Tettenhall. Carrying building stone for long distances

by water was an ancient and tested practice but it is

likely the stone was carved near the quarry at Bath. On

the 14th May 1833 Rickman records ‘some good stone is

come’ but he doesn’t say from where. It is recorded that

he also intended to use Bath stone for a house at Lough

Fea in Ireland in the 1820’s.

The diaries also refer to the

possible re-use of materials from the house that was

being demolished, mainly timber. On the 2nd January 1834

he records making a greenhouse design for Tettenhall.

Unfortunately, the diaries stop in April 1834 when

Rickman had a catastrophic attack of liver disease, so

we have virtually nothing written about the later

construction of the house or the nature of the problems

causing the rift in relationships.

Besides the house itself Theodosia

had two more architectural ‘treats’ to beguile us. The

first was her lodge in Wood Road and the second was her

grand staircase window.

|