|

10. More exhibitions and more critiques At the Paris International Exhibition of 1867 Wallis superintended the British Section of the section on the History of Labour. And he was on five of the juries, which work he undertook, according to the Biograph, “more out of respect for his colleagues than for any admiration of or belief in the system of awards”.

In the end the jury selected for awards those items whose originator could be identified with some certainty - in many cases the Turkish authorities did not seem to know who had produced the items. Wallis says: "The awards are curious and all to women, except a prize to the Tailors' Association of Janina, for Albanian costumes. Whether the daughter of the Turkish gentleman with an unpronounceable name ever received the awarded medal, or the girls of Bukudgy and Itsche, or the wives of Carabet and Terzy got information of the 'honourable mention' made of their embroideries, is a matter of speculation to this hour with those who desired to do them justice". These problems of practicality, culture and communication are certainly some sort of argument against these sorts of awards. Maybe Wallis also took the attitude that, though you can tell the good from the bad, very many people might reach a high standard within which it was impossible to make distinctions. It is a debate which was still going on throughout the twentieth century, arising notably when art schools were constrained to award degrees which conformed to those awarded in the sciences and other spheres.

In 1871, Halen tells us, Christopher Dresser gave a lecture “Ornamentation Considered as High Art”, a lecture which was “a severe attack on the naturalist school and on the South Kensington Institution". Dresser also “raged against the authorities of the South Kensington who were not able to find men who had art-knowledge and technical knowledge combined”. Here Dresser was, of course, riding his hobby horse, that an understanding of the technical aspects of materials and production methods was essential to good design. But Wallis too had always advocated exactly the same thing and had done so before Dresser. He was one of those attending this lecture and was probably one of those at least trying to employ the rara avis that Dresser wanted. But Dresser praised Wallis’s ability to communicate with manufacturers. In any event Wallis must not have taken too much offence if Halen is right in saying that Dresser also “stressed the importance of proper museum labelling and cataloguing, and George Wallis, who was present at the lecture, clearly took note of this, because he soon afterwards encouraged the printing of the South Kensington Museum Handbooks, which became very popular during the late 1870s and 1880s”. Why Wallis, who had long advocated close relationships between the London museums and provincial ones, could not have thought of this for himself, Halen does not say.

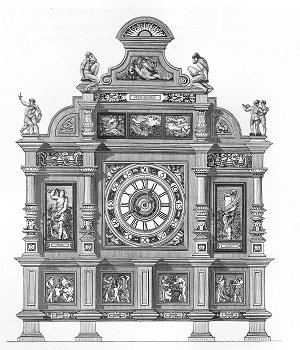

In 1871 too The Art Journal Catalogue of the

International Exhibition, 1871 was published, again with Wallis

acting as commentator and critic.

“Twenty years ago nothing could possibly be more inappropriate than the

whole mass of designs executed for carpets;

but now the fact that the carpet is a decorated covering for the

floor, and that the floor is a horizontal place to be walked upon, and

that the design ought not to contradict these facts, seem to be pretty

generally understood and acted upon, thanks to the incessant attention,

and consistent action, of a few able artists, such as Mr. Owen Jones,

Sir M D Wyattt and Dr. Dresser, whose attention to this department of

industrial design has had a marked influence on its present position”.

Here Wallis refers to artists (not to designers or ornamenters)

and claims no credit for himself.

He never did, directly, but this does reflect his feeling that it was in

the traditional arts that the basis of good design was to be found.

He does not seem to have gone along with Dresser’s view of

ornament abstracted from nature as being a higher form of art and

ornamentation – but nevertheless he seems to have appreciated what

Dresser was trying to do and is one of the few Victorian design gurus to

give him a mention.

Wallis continued to write a good deal and to speak on his favourite topics. The Biograph mentions that he addressed the students of the Manchester School of Art in January 1878 and that in doing so contradicted “as an eye witness of forty years' standing, the theories of people who held that no progress had been made in the art of design, as applied to manufacture and decoration, in the last twenty or twenty-five years”. This speech was later published under the title “Decorative Art in Britain – Past, Present and Future”. It does act as a summary of much that he had thought and done over his lifetime. He also continued to write for the Art Journal. Their volume for 1880 carries a series of articles by him in which he illustrates and assesses a wide range of art designs and which continue to assert that progress had been made in industrial art and that this was the result of the work of art schools and the effects of local, national and international exhibitions. |