|

11.

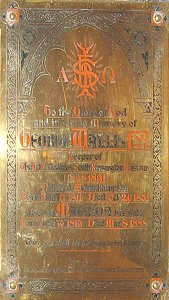

Last years The Biograph mentions that Wallis had “for many years past” painted only as a hobby and never exhibited his work. It seems that no one has ever identified any manufactured article as being designed by Wallis and it may be that he never did that sort of work after he left Wolverhampton for the second time. His life and work was that of the museum curator, art critic, promoter of art education and art educator not just of art students but also of workers and the wider public. George Wallis continued working at the South Kensington Museum until 1891, when he had reached the age of 80. He died a few days after his retirement. Jones also mentions a personal detail – one of the few we have of Wallis: “During his busy life he found time to run down to Wolverhampton and visit his uncle and aunt in their old age, and comforted them by many acts of thoughtful kindness. The old people were proud of him, and felt greatly pleased with his affectionate attentions. He was ever ready to help the good old town and forward its interests, especially in relation to art and manufacture.” The correspondence of 1883 about the lives of Bird and Barney, already referred to, shows Wallis' continuing association with his home town. The letters show, for instance, that when Wallis eventually located, in Oxford, a bust of Bird, he had plaster casts made of it and presented them to the Royal Academy (of which Bird was a member), to Bristol (where Bird had spent much of his working life) and Wolverhampton (which was the home town of both Bird and Wallis).

In 1875 Wallis published a book about Swedenborg, so it is possible that he was, at least for a time, a Swedenborgian.

As late as 1919, on the occasion of the retrospective exhibition of Wallis's work, the local newspaper, the Express and Star, wrote: "One of the objects of our School of Art is to effect a complete union between arts and crafts, and the purpose of the handicraft side is to afford students engaged in local art industries further opportunities for practice than can be obtained, usually, in a workshop. There is no reason why a really useful article should not be beautiful also and the fact that we have made progress in this direction is due in no small degree to the labours of men like the late Mr. George Wallis". Anthony Burton, in an article dealing with the usefulness of the South Kensington collections, says, in the abstract of the article, that "The best expositor of the Museum's educational philosophy proved, unexpectedly perhaps, to be the scholar-connoisseur Robinson, rather than the design reformer Cole or the art teacher Wallis". But the body of the article tends to suggest only that Robinson spoke and wrote more about the theoretical basis of the Museum's art and design theories. There can be little doubt that Wallis made a considerable contribution to industrial art education generally and to the Victoria and Albert Museum as a teaching institution. According to Whitworth Wallis, in his speech at the 1919 retrospective exhibition, William Morris said: "Your father has led a long and useful life. He sowed the seeds from which, later on, many thousands have culled the flowers".

So what, towards the end of the day, did Wallis make of his world during his time? The series of Art Journal articles, referred to above, start with an introduction by Wallis. This may be taken as a summation of his mature views on many aspects of his subject. He writes again about the suggestion that in art manufacture “so far from having gone forward, we have gone backward”. Of course, to Wallis, who had spent his life trying to go forward, such views amounted to an allegation that he had failed. He vigorously attacks these backsliders, starting by pointing out that were people not much better educated about such matters than they were, they would not be in a position to criticise the present state of affairs and probably would not even care about it. “An interest in Art has been created in the family circle.... The fact that people think and talk, or care for congruity in style, and are lead into ultra-medievalism, or the last new Art craze of the professional furnisher and decorator ... “Queen Anne”, is something to congratulate the nation upon, since it shows an evolution from the depths of the upholsterers barbarisms, as connected with the Arts as applied to domestic purposes and uses.” Those who say we have not progressed should have “waded through the pattern books of manufacturers in the various departments of industry” from which they would have learnt “that their fathers either admired most hideous things or that they had to tolerate then because the manufacturer and designer were too ignorant of the most elementary principles of decorative and ornamental art to produce anything better”.

Wallis seems to be saying that what the art schools have produced may not be of a great standard but at least it is better. That the improvement has not been greater he attributes, at least in part, to failures by the art schools. One problem had been that, when the Schools of Design were first established there was “a notion abroad that decorative and ornamental Art had little in common with pictorial Art” so that students were restricted “entirely to the study of conventional ornament as it had existed in past ages, and to plant forms, and by no means to travel out of this by studying the human figure”. This, of course, relates back to Wallis’ departure from Manchester. He is by no means saying that the ornament of past ages should not be studied – he is not attacking Owen Jones and all his followers. Nor is he saying that the study of plant forms should be abandoned. Such a study was his interest from his earliest times as a teacher – but note that there is no suggestion here of the interest in plant forms being taken to Dresser-like extremes. What he was arguing for was “the proper consideration of every phase of Art”. But this was not to be a broad and generalised education solely in Art: it was always to be directed to its relevance to the production of manufactures. For Wallis “the artist has to remember that the forms should always be considered in relation to the use of the object, and that the decorative details should embellish the form or surface, and never interfere with the integrity of either, whilst both form and detail should be subordinated to the material or materials in which the object is to be made, and its easy production by the process or processes applicable to its manufacture”. In all of this Wallis is not far from Dresser. It seems to be in the application of the principles that Dresser differed. But Wallis also fears that “at the present time ... decorative Art has fewer attractions for nine-tenths of the students of our schools that it has ever had, Pictorial Art is everything – ornamental Art comparatively nothing”. Wallis seems to be pointing out that the art schools, set up to be schools of industrial design, were now turning into fine art schools and that change would do nothing to benefit industrial design. To judge by the general standard of industrial design in this country in the first half of the 20th century, he was right. |