A Tale of Two Squares: St. John's and St. James

by Maureen Hunt,

with photos by David Clare

and additions by Bev Parker

This is the story of two squares in Wolverhampton, one of which survives, the

other does not. What is their story? And why did one survive and not the other?

St. John's Square is situated near the top of Snow Hill, and is still a

busy place, thanks to the many offices and businesses that are based there. St. James'

Square, near the west end of Horseley Fields, disappeared in the 1960s, and has

since been almost forgotten.

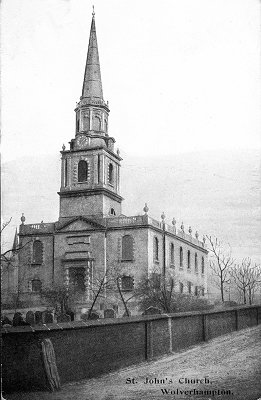

This early twentieth century postcard

shows St. John's church and the high brick wall which hid the

gravestones from the residents' view. |

The origins of the

squares and the two churches

St. John's Church is the second oldest church in the City

Centre, and the first to be built within its own square.

By the mid eighteenth century the population had increased to such an extent that another church was

urgently needed. The site chosen for the building, lay to the

south of the town in almost open countryside, as can be seen

from Isaac Taylor's map

of 1750. The area is marked as 'Windmill Bank' and the 'Cock

Closes'.

St. John's Church was built under the terms an Act of

Parliament, passed in 1755 which allowed a fourth chapel of ease

to St. Peter's Church to be set-up. The first chapel of ease

was built

at Wednesfield in 1746, followed by one at Willenhall in 1748, and

another at Bilston in 1753.

Although details of the plan are not clear, it seems that the

new church was intended to serve an area likely to see

expansion. Snow Hill and the surrounding streets were rapidly

being developed, as the town extended southwards.

The church opened, although not complete, in 1760, and the

buildings around the square slowly appeared during the next 100 years or so. |

| The fact that

four roads meet the square in a symmetrical way (Church Street,

Bond Street, George Street and a short street opposite Bond

Street leading to Church Lane) strongly suggests development

according to a plan. The square seems to have began life as an

elegant secluded square, echoing the lovely Georgian buildings

in George Street, at the eastern end. As time progressed,

buildings of a lower standard were added, giving the a square a

haphazard appearance. |

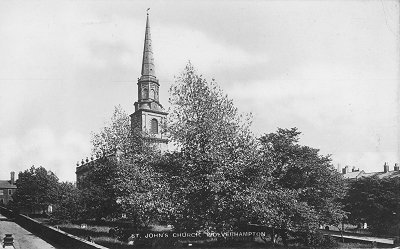

A later postcard shows the church and

the wall on the other side of the square. To the right the

houses of the square can just be made out. |

| By the early 1830s the western end of the square around

Church Street became industrialised when James Tonks & Sons

opened their brass foundry. This was followed by the

building of a number of small workshops at the eastern end

of Church Street, which included a coal yard. |

|

From the 1842 Tithe map, showing the

nearly fully developed square. |

| St. John's Square, as its name implies, is a square surrounding a church of the same name. But St.

James' Square existed at least 50 years before St.

James' church was built. The square was a few hundred

yards away from the church, which seems to have taken its name

from the square, rather than the other way around.

Local historian John Roper, described it as follows: "The name of this area of the town has baffled historians. Long

before the church was built, the large Georgian Square was known as St.

James' Square, but there is no record of any connection with this particular saint

in the Middle Ages." The Square was not exactly square and it had only two streets leading to it,

one from the north-west corner leading to Horseley Fields and the other from

near the south-east corner leading to Union Street. |

The location of St. James' Square, and the not too distant

St. James' Church, which may have been so named because of

its proximity to the square. |

St. James' Vicarage in St. James

Street. The above photograph,

taken from the north side of Horseley Fields, shows the

vicarage on the corner. Courtesy of Roger Jennings. |

| The first map showing both of these areas is Godson's map of Wolverhampton.

This map, dated 1788, although of poor quality, gives the names of all the

streets in Wolverhampton at that time, together with the number of houses and

their inhabitants. Although by this date St. John's church had been built for

some time, there as yet were no dwellings in the Square itself, though Bond

Street, leading from Temple Street through to the church, is mentioned as having

nine dwellings and forty inhabitants. Meanwhile, on the other side of the town, St. James's Church was still fifty

years away from being built; but St. James' Square was already in existence and

it too had nine houses and forty inhabitants. This may suggest that, as a

residential square, St. James' had at least chronological priority. Indeed the

general direction of development seems to have been much more towards the east

than the south, which must have been considerably assisted by the opening of

the canal in 1772.

By 1792, as shown in the Wolverhampton Rate Book, there are still no houses

in St. John's Square, but Bond Street seems to have grown. The nine dwellings

have increased in number to fifteen. St. James' Square has five commercial premises

mentioned:

Joseph Sapwell, bucklemaker

Obadiah

Walford, victualler

John Millington, keymaker. No. 2 St. James' Square.

Thomas

Evan, joiner and huxter

John

Cadwallader, locksmith. No. 9 St. James' Square. |

|

|

| The squares in the nineteenth century By 1809-11 the trade directory still does not mention St. John's Square, but

now, as well as Bond Street, George Street is listed. This indicates that at

around this time, the link road between St. John's Church and Snow Hill was

being developed. In this particular directory, St. James' Square is not

mentioned either. But a "Horseley Fields Square" is. Presumably this was the

same square. |

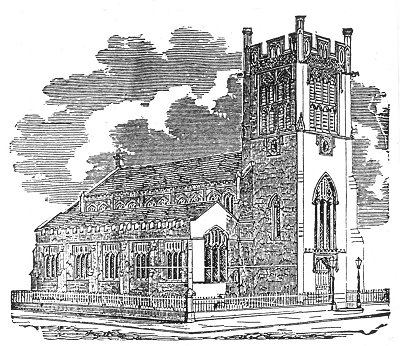

St. James Church, built in the gothic style. The architect was a

Mr. Egington and the builder, a Mr. Snow of Leamington. |

St. James' Church was built between 1840 and 1843. It was consecrated on 12th

May, 1843, and had north and south galleries, and a west gallery for the organ.

It had a single bell in the tower, and could seat 1,200 people. The vicarage was

built in 1847 at a cost of £1,100.

The church was renovated in 1924, at considerable cost, and an oak choir

screen was added in 1929.

By the 1950s the size of the congregation rapidly fell, which led to the

closure of the church and its demolition in 1955. |

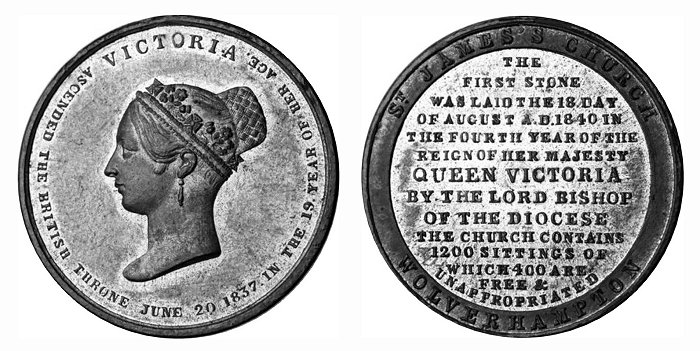

The commemorative medal struck for the

laying of the church foundation stone in 1840. Courtesy of David

Clare. |

| A property sale advertisement in the Chronicle in 1817, gives a clue to the

building of the first houses in St. John's Square. The advertisement refers to

the sale of three dwelling houses in St. John's Square and Bond Street, and a newly

erected dwelling house in St. John's Square "together with the school thereto

adjoining". So this is presumably the time that the Square began to take shape. Coincidentally, appearing in the same newspaper was an advert for sale of a very

large amount of timber, the property of Obadiah Walford, victualler of St. James' Square. Clearly Obadiah was not just a licensed victualler. As the

timber appears to be on the premises in St. James' Square,

we perhaps have an indication that the square and its area

were already becoming more commercial and less residential

than St. John's. |

|

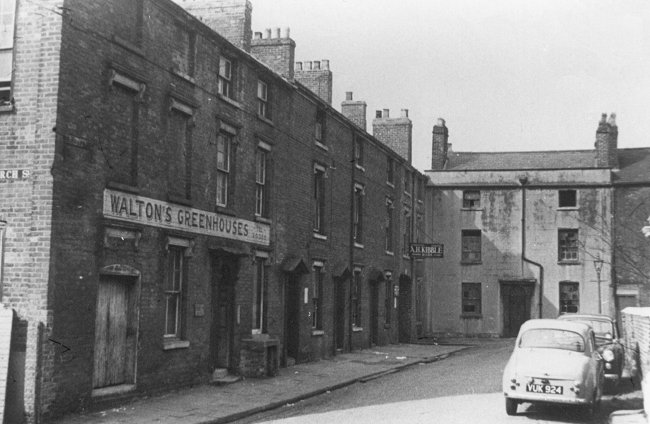

St. James' Square. Courtesy of

David Clare. |

| In 1840 the two churches, St. John's and St. James, became

linked together for a day. The date was Tuesday the 18th August 1840. That was

the day the foundation stone for St. James' Church was laid. The Chronicle for 19th

August had an extensive report of the proceedings, which occupied almost a whole

day, starting with a service at St. Peter's, with the Bishop of Lichfield in

attendance. Refreshments were then taken, and by 4.30 a procession had assembled

at St. John's, from where it proceeded, on foot, to the site of St. James'

Church,

nearly a mile away. The Chronicle noted that "his lordship, who wore his episcopal habit, was an object of considerable curiosity to the crowd, who

completely lined the way from George Street to Horseley Fields". He formally laid the foundation stone, then hopped up onto it to address

the crowd. In his address he refereed to the "spiritual destitution" of this

part of the town and the need for the church. When he had finished these few

kind words, the Rev. W. Dalton made a speech in which he also "forcibly

portrayed the spiritual destitution of the town". A crowd of "several thousand

people, who appeared to take a lively interest in the day's proceedings,"

then dispersed. |

| |

|

|

|

|

View a list of

inhabitants in 1851 |

|

|

View the

1879-80

electoral register |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The north-western corner of St. John's

Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| Melville & Company's Wolverhampton Directory of 1851 shows that

St. John's Square seems to have been quite a fashionable part of

Wolverhampton to live in. Under the heading of "Gentry" there

are 6 people listed as well as a professor of music (who was

also the organist of St. John's), a portrait and historical

painter, two school masters, a dressmaker and a furrier. In addition there were two boarding houses, a ladies seminary, and a

classical & commercial school. Samuel Tonks is also listed. He was the owner

of the brass and bell foundry at the western end of the Square, and lived in Church Street. Also listed was "James Gibbons,

factor, St. John's Square." St. James' Square, at this time, only had one person listed under the

heading "Gentry", while the rest of the Square's 32 dwellings were occupied by

roughly the same professions as its counterpart. It too boasted of two ladies

schools, two teachers, a day and evening school (run by Charles Trevor) and

Monsieur Willenboard Buscot, a professor of the French language. John Fell & Co.

were the Brass Founders of this Square. The notable ale

house in St. James's

Square was the George Inn, sometimes referred to as the "George III".

In 1851 John Lane was the victualler.

As well as the same respectable trades, as in St. John's Square, St.

James' had two coal merchants and two corn and seed merchants. Perhaps these

last two trades were carried on in this Square because of its close proximity to

both the canal and railway.

The electoral register for 1879/80 shows that St. John's Square was still

holding on to its status, with a surprisingly similar list of occupations to

that of 1851.

The squares in the twentieth century

In the 1901 Red Book there were seven people listed under "Private" in St.

John's Square. Other listings of interest are the "Central Registry Office" and,

under the heading of "India Rubber Goods Merchants", is the "Wearwell Cycle

Accessories Co". Also shown is A. G. Haselock (jnr), a file and rasp manufacturer. There were three credit drapers, no less than three professors of music,

and a pianoforte dealer. The square was probably becoming more commercial and

less residential with the continued expansion of Wolverhampton as an industrial

centre, and the development for industrial purposes of the land south of the

square.

No "Private Residents" at all are listed for St.

James' Square in 1901. There were only six trades people

noted:

Wootton Bros., nail & cut

tack manufacturers

Mulliner & Co., paper box

manufacturers, and printers

Cozens W & Co., provisions merchants

J.

Fell & Co., brass founders

Wing & Webb, hardware merchant

M. A. Voyce, licensed victualler,

"George III" |

|

The George III pub was still in existence, and Mulliners, the

printers, and Cozens, provision merchants, were also there. The three of them remained

in the square right up until its demolition. By 1930, surprisingly enough, some of the families living there are still the

same, but again this is more noticeably so in St. John's Square than in St.

James'. |

|

The northern side of St. John's Square.

Courtesy of David Clare. |

| By the year 1948, both squares were becoming

decidedly rundown. In the Wolverhampton Chronicle, dated 15th April,

1948, an article by Kenneth Bird was already lamenting "the drab

facades of the buildings and the pervading air of decayed

elegance" of St. John's Square. He attributed the square's

descent in the world to the building of galvanising plants in

the vicinity, and the power of the car to sweep people out into

suburbia. |

|

The north-eastern corner of St. John's

Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| The vicar, the Reverend J. Hartill, complained to him of vandalism, the use

of the stained glass windows in St. John's Church for catapult practice, and "acts of

horrible desecration", with piles of refuse in the churchyard and the vaults

smashed. He blamed local children.

A local business man, Mr. M. H. Costley, who

operated an export business from the church end of George Street, told Bird: "I

can remember this square 60 years ago (about 1888), and things were very

different then. I used to go to school in the square. The master was a man named Bratt, who didn't believe in sparing the rod. Mischievousness or a failure to

master the principles of reading, writing and arithmetic lead to a good

thrashing across one of the desks. He was a real old-fashioned pedagogue, with a

high collar and a bow tie.

When I walked to school I used to watch the horses

drawing phaetons away from the bigger houses. It was a very picturesque sight.

In particular I used to take notice of Mr. Richard Briscoe, founder of a now

famous business house. He was a most imposing gentleman who used to live at 10

George Street. Later he moved to Chillington Hall".

Another local, Mrs. E.

Hall, insisted that the neglect was comparatively recent, apparently in the last

twenty years or so. |

|

Another view of the north-eastern corner

of St. John's Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| The electoral registers of 1955,

show to what extent the Squares' population had dropped in

number. St. John's still had thirty-five addresses registered as

having voters living there, while St. James' Square had only

three.

On 25th July, 1956 the Birmingham Post took up the theme. Its reporter, W. P. Kirkman, again mentioned the "lost, neglected air"

of St. John's Square, and

again interviewed the vicar, the Reverend J. Kirkham, who pointed out that

since he came to the living in 1931, "not a single new house has been built in

the parish and whole streets of houses have been pulled down". Kirkham found

another business man to lament the situation. Mr. J. W. Whitehead then had his

printing works in the south east corner of the square. He recollected that even

when he first came to the square, in 1896, the wealthy private residents were

beginning to move out. He was now preparing to move his works to new premises on

Snow Hill, in anticipation of the council's plans for a new road being approved.

Kirkham also comments that industry (which he would have noted all

round) seems to have passed the square by and he found only 2 "miniature

factories". One was a tinsmith, who ran a two man business making tin

boxes for motor car accessories. But he did notice the popularity of the

Spirit Vaults, which stood on the corner of the Square and George Street.

For years it had been an off licence, but now had a six day

licence (presumably out of deference to the church) and a large

clientele.

Kirkham noted that it was the needs of modern transport that had sounded the

square's death knell. He was referring to the coming of the ring road. But he might

also have noted that it was the car which had done so much initially to lead to

the square's decay. |

|

The south-eastern corner of St. John's

Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

|

The southern side of St. John's Square.

Courtesy of David Clare. |

| Also in 1956, on 5th June, an article appeared in

the Birmingham Post about what had happened to St. James'

Church. Because of declining attendances, the church had been

closed in September 1955, and the parish had been split,

part of it being added to St. Peter's and the other part to St.

Stephen's. An accompanying photograph shows the church being demolished, but the article

points out, some bits of it were going to newer churches. St. Peter's, at Rickerscote, near Stafford was to get the stone pulpit and font, the oak screen

and the bell. St. Joseph's Church at Merry Hill, Wolverhampton, was to get the organ,

the lectern, and some of the church plate. |

|

Another view of the southern side of St.

John's Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| But both squares were now embarking on important phases

of their lives. For one of them there was partial survival

and renewal; for the other, destruction. St. John's Square

had clearly deteriorated badly. No doubt it was going down

hill before the Second World War. Lack of maintenance during

the war would have made things worse. As soon as post

war reconstruction might have started, the area would have been

blighted by the threat of the ring road, and slum clearance. It was a fate shared by many Georgian and Victorian areas throughout the

country, and the spirit of the times was to demolish and rebuild. The south side

was flattened and replaced by the ring road. |

|

A final view of the southern side of St.

John's Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| Not until the mid-60s did the enthusiasm for

destruction wane. The result was that many buildings on the west

side of St. John's Square were pulled down to be replaced by modern offices. The new

office block on the north west of the square, designed by Twentyman, Percy and Partners for the Borough Council, won a

Civic Trust Commendation for its "courageous attempt to

re-establish an 18th century square." The new work has a strong

link in scale and rhythm with 18th century practice and the colour

relates well with the church and its surroundings. The Trust was not

so flattering about the other new buildings on the north side. The whole

of the south side was demolished, making the square no longer a square,

though it retains that name. The church, whose congregation had been somewhat

boosted when it joined forces with the Lithuanian Church, was saved by a massive

appeal, conducted nationally. The whole church was eventually re-cased, an

enormous undertaking, largely financed by Sir Jack Hayward. |

|

The western side of St. James's Square.

Courtesy of David Clare. |

| St. James's Square had no reprieve. People had moved out of the area, largely because of the

massive slum clearance scheme on that side of town. The square

had

fallen on hard times, and spent its last days with a few scattered

businesses, and a bus terminal. The square eventually fell to the sixth and final

stage of the ring road.

So thoroughly has it vanished, that who

now could point, with confidence, to the place where it once

stood? |

|

Another view of the western side of St.

James's Square, as seen from Horseley Fields.. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| Conclusions Throughout the history of the squares, the impression given is

of St. John's superiority over St. James'. St. John's was always the "better"

area. The fact that it was largely planned, and that it centred on a fine

classical church, always gave it the edge over the more industrialised St.

James'. It may

well be significant that the residents of St. John's Square appear to have

stayed living in the same house from one generation to another, while in St.

James' Square, the residents seemed to be "just passing through".

The preference for St. John's over St. James' is reflected in

the numbers of photographs in the Wolverhampton Borough

Archives. St. John's church has thirty-five photographs, and its

Square thirty-three. There are only four photos of St. James'

Square, two of these being the same picture from a slightly different

angle. |

|

The north-eastern corner of St. James's

Square. Courtesy of David Clare. |

| Perhaps the ultimate humiliation in the history of the square, and

also the church of St. James, comes from its failure to be remembered in the current ring road

names. Surely the most obvious name for the final stage of the ring road should

have been "St. James'". But, it seems, some patriotic person, decided that as St. George's, St. Andrew's and St. Patrick's were

all included around the ring-road, St. David's should also be included. The fact

that St. George's, St. Andrew's and St. Patrick's are all names of

churches that either once stood, or are still standing, on or near the

road and that St. David's never was, seems to have eluded those

responsible. Surely, if for that reason only, the name of the final

stage of the road, should have been St. James. |

|

The ring road today, showing the location of

St. James' Square, and St. James' Church. |

| I would like to thank David Clare for his help in producing this

section. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|