| Introduction

Manders were once a well known paint and ink

manufacturer whose products sold both at home and

abroad. The company was at the forefront of the paint

and ink manufacturing business and held many patents for

innovative inventions and manufacturing techniques,

thanks to extensive research and development.

Manders took over several other companies and became

a large local employer with a workforce of around

1,000. The company's products were second to none and

became well known for their quality and reliability.

George Cox worked at Manders Heath Town factory for

42 years, starting on the shop floor and ending up as a

senior manager. His memories provide us with an

important insight into life at the works and the methods

used for the manufacture of paints and printing inks.

Beginnings

I came out of the forces in 1945 and joined the police

force, during which time I had my first encounter with

Sir Charles Mander. I was based at Red Lion Street

Police Station, and whilst on duty I saw a car parked on

the wrong side of Darlington Street, opposite Beatties.

In those days cars had to park on

one side of the road one week, and the other side the

next week. The owner was Sir Charles Mander. I walked

over and said “Good afternoon Sir, you have been parked

on the wrong side of the road for 2½ hours”. Sir Charles

replied “Oh yes constable, I had a meeting with the

borough engineer at Barnhurst, we are having some

changes you see.” I replied “I am sorry but you are

parked on the wrong side of the road. I shall have to

take your name and address. Have you got your driving

licence?” He said “No I haven’t got it”, to which I

replied “OK can you see that you take it to your local

police station within the next 48 hours”. Sir Charles

handed me a pen to write the details in my notebook and

said “Constable you can use that, it’s a biro pen, it

writes underwater. I paid £2.10s for that”. That’s the

first time I ever saw a biro.

As a result Sir Charles was taken

to court but wasn’t present. I had to be there to give

evidence. He was fined £2. Six weeks later I was working

for him but he didn’t realise that. Someone however told

one of his nephews who came to me and said “You

prosecuted my uncle didn’t you.” To which I said “yes”.

The Ink Department

I started at Heath Town in March 1946 in the ink

department as a shop floor operator making printing ink

on a 3 roll mill. The mixed powders and ingredients were put into a

pan and poured onto the rollers in the mill, where they

were thoroughly ground. A knife pressed against the mill

to remove the ink, which went through the mill 3 or 4

times, depending upon the type of ink. Each time, the

supervisor tested a small batch of the ink which was

sold by weight, and so finally weighed out on scales to

2lb, 4lb, or whatever. In the early days the ink pigment

was soot. |

|

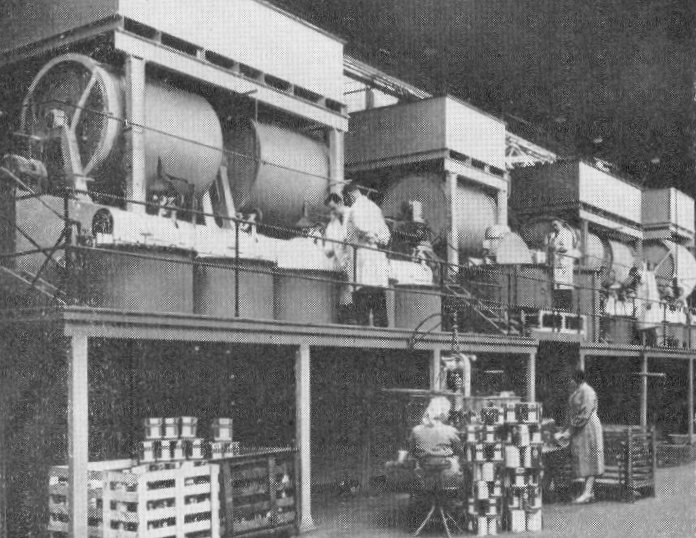

3 roll mills in the ink department

at Heath Town. |

| There was also the liquid ink department, an

offshoot of the ink department, where non-poisonous inks

were produced for such things as food wrappers. |

A 3 roll mill. |

| The Paint Department

In 1954 I moved to the paint department to become

supervisor over the ball mills, which made the paint. I

was supervisor over the four men who made the bulk of

the paint. There were 6 ball mills. Five of them made

250 gallons at a time and the other made 500 gallons.

When I first started, 45 percent of each mill was filled

with 2inch and 1inch seaside pebbles, formed from hard

rock. Every day the mills were emptied and refilled.

White paint in the main is titanium oxide which was

mined in Norway and France. Most of ours came from

Norway and was shipped to Grimsby. When it’s first mined

it is as black as the ace of spades. It is then

calcinated, or cooked, and burned to a powder which

turns it white. Today it’s used in all sorts of things such as face

powder, and I think it’s used to colour bread. White

paint also contains varnish, white spirit and extenders

such as china clay. The extenders reduce the amount of

titanium oxide that is used.

Titanium oxide on its own would make the paint so

expensive to produce that you would never sell it. The

laboratory had to decide how much titanium oxide we

could use and how much extender to use without spoiling

the product. |

|

The ball mills. |

|

The production department and warehouse staff.

Courtesy of George Cox. |

|

Manders annual supervisory dinner

at the Molineux Hotel in 1954. I had been appointed as a

supervisor in the paint department in the early part of

that year. Courtesy of George Cox. |

|

George from the photograph above. |

Paint also contains lethasin which

is made from ground nuts. We used to buy-in 40 gallon

drums, it looked like apricot jam. When added to the

paint it kept the pigment in suspension, preventing it

from dropping to the bottom of the tin.

We made our paint a little thinner

so that it was easy to apply, but without reducing its

covering properties. Manders paint was as good as any

other. If we were making reds, greens,

browns or blacks we added liquid dies to the mill. Other

dies would be added later by the tinters to produce the

right colour.

The mixers put the pigment,

varnish, and spirit etc. into the manhole then clamped

the lid on ready for grinding.

The mill then ran for 18 hours. The

next day a sample would be taken and I would check it to

see that all of the particles of pigment were fully

covered with varnish and spirit. I checked it with a

Heckman gauge. If it wasn’t ready the mill had to keep

on running. |

Presented with my 25 years long

service award. Philip Mander is in the centre and George

Cox is on the right. Courtesy of George Cox. |

|

As the years went by the pebbles were replaced by

½inch and 1inch steatite balls. The smaller balls had

more touching points and so allowed the running time to

be reduced to 6 hours, so that two lots of paint could

be produced each day.

The ball mills were very noisy, the middle mill

contained 2½ tons of steel balls, which sent me deaf.

The pigment eventually became finer and finer so that

grinding wasn’t necessary and you could mix the paint in

a vessel. Grinding was then only necessary for strong

colours. After milling, the paint was then

dropped into the mixing vessels where it was tinted.

There were 6 tinting staff, called tinters, who tinted

the paint to the right colour. Pastel colours all

started off as white. We made 132 colours. Before the

paint went into the tins a sample would be sent to the

laboratory to check the colour and the standard. The

paint would then be put into portable filling machines

and the tins would be filled by a staff of 30 people.

If a strong colour, say red had

been milled, the mill would be cleaned back to white. We

put in white pigment, powders, varnish, and spirit. It

not only cleaned the vessel but made red primer. When we

made black, and the mill was cleaned back to white, we

again added the white pigment etc. and produced grey

undercoat. We did still however have to put some spirit

into the mill afterwards to properly clean it before its

next use.

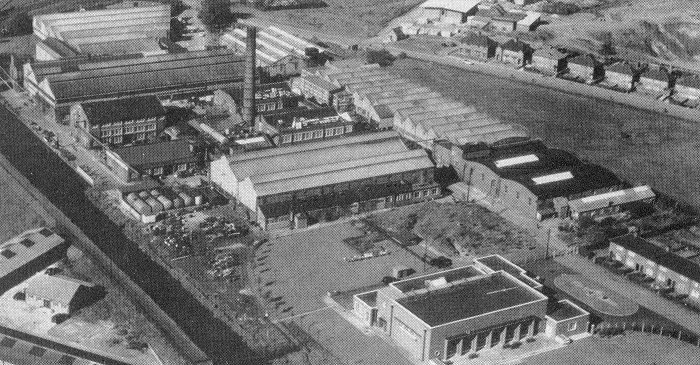

Heath Town Works.

The paint industry revolutionised

painting and decorating. When painters and decorators

first started, a decorator would be called to a house to

do a job. The lady of the house would state which colour

she wanted and the decorator would return to his

premises to mix the paint. It was made from white lead,

a dangerous substance. He had various colours and would

mix the paint to the lady’s requirements. This all took

a lot of time and he didn’t get paid until he started to

decorate after she had accepted the colour.

This all changed when paint

manufacturers began to produce a wide range of colours

which they supplied directly to the decorators. |

|

A water paint mill using a stone

wheel. |

Around 1954 we made our first emulsion paint. Before

emulsion we made water paint called “Aqualine” which was

made in an edge runner, like a great big round pan 2ft

deep and 8ft diameter. Inside a big stone wheel ran

round to grind the paint.

The first emulsion was white and our first 250

gallons were given to our best customers. It was made in

the water paint department and became very successful.

Everybody used gloss paint outside, in kitchens, and in

bathrooms because emulsion wasn’t suitable. |

| As years went by the paint improved and could be

used anywhere, even outdoors. Emulsion then took over

from much of the gloss. Manders always kept at the

forefront of the technology, they had a good staff. The

technical laboratory did research into both paint and

ink. The Paint

Warehouse |

|

In 1960 I moved to the paint warehouse

to become the paint warehouse manager. There were 40

people in the warehouse where paint tins were put onto

wooden pallets, each containing 100 tins. Large volumes of paint were going

through there. By December 1961 Manders had made 500,000

gallons of paint. Ten years later the company made its

millionth gallon of paint. |

|

The paint warehouse staff in 1964.

Courtesy of George Cox. |

|

The paint warehouse. |

|

Another view of

the paint warehouse. |

|

The paint department

production team in 1964. Courtesy of George Cox. |

Paint department and warehouse

managers and supervisors. Courtesy of George Cox who can be

seen 2nd from the left on the front row. |

| I occasionally went to the old John Street works in

the centre of Wolverhampton. The offices were on the

left hand side of the street, as you went down from

Dudley Street and the varnish works were opposite.

At that time the works were very old fashioned. The works closed in the early 1960s and production

moved to Heath Town. |

|

Some of the

cottages in John Street that were demolished

as the works expanded. Courtesy of George

Cox.

|

| Varnish making and my

later years |

| Manders had their own range of varnish, first

produced in 40 gallon lots. In 1820 the company started

to make church pew varnish which did well because it

wasn’t sticky, so the congregation didn’t stick to the

seats. It was also sold to the Queen for use as

carriage varnish, for which it got the Royal Diploma.

Early varnish makers were called “gum runners”. They

made varnish in a vessel which stood partly below the

ground and was heated with gas burners. The men put in

spirit, and varnish, and boiled it up to temperature.

The thickness depended upon the temperature. When they

were experienced they could spit into the liquid to tell

when it was ready. They stirred the contents with a

wooden paddle, a very dangerous process. |

Early varnish making. |

| The company used to make a range of 30 or 40

different varnishes, but many were similar so the range

was reduced to 8, 9, or 10. When varnish was made at Heath Town, 500 or 1,000

gallon batches were pumped into storage tanks on the top

floor through a pipe line. The varnish was then poured

into portable 100 gallon vortex mixers before being put

into tins. In 1894 Manders opened the Wednesfield Works in Well

Lane, and later built the Heath Town Works on the site

where a munitions factory produced phosphorous poison

gas during the First World War. The works officially

opened in 1931 and were extended over the years. In World War 2 camouflage paint was produced for the

ministry in 10 gallon drums. |

|

The old methods of producing

varnish were still in use at Manley & Company in Lower

Horseley Fields in the mid 1950s as can be seen from the

photograph above. |

|

Heath Town Works. |

|

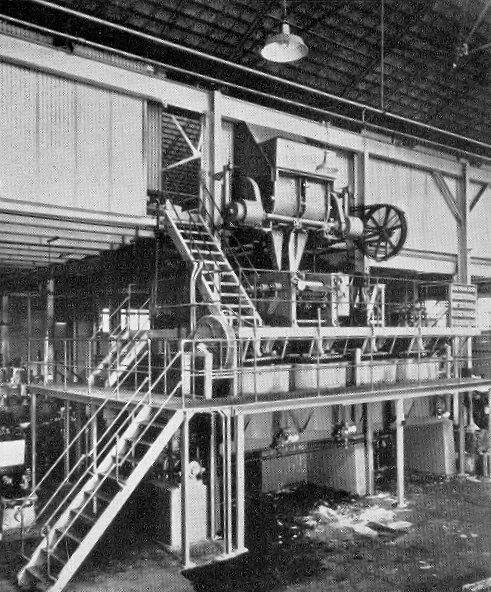

Combination plant used to manufacture white enamel. |

When I first joined, several members of the Mander

family were directors. There was Sir Charles Mander, Sir

Geoffrey Mander, Vivian Mander, Philip Mander, and

Gerald Mander. Philip Mander died on a train from

London. He was a nice chap who would talk to you. His

sister married Bill Purslow who became the Works

Director.

Geoffrey Mander started the Joint Works Council in

1944, after Ernie Bevan started the 40 hour week. They

used to meet in the offices. There were the

representatives of managers, supervisors, shop floor

operators, and the senior shop steward. I was on it as a

supervisor, but it died a death when Geoffrey died. We

then had individual departmental meetings. |

|

In 1967 I became works manager when

the previous works manager Alan Capstick moved to the

ink department as Ink Director. He later returned to the

paint department as Paint Director. I stayed in the job

until I retired in 1988.

I went to the works in 2006 and

saw that little was left. It was very sad. So much had

been demolished and altered. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Mander-Kidd |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Sports and Leisure |

|

|