| By the 17th century the population of Darlaston had

grown considerably. In 1601 Queen Elizabeth's Poor

Relief Act was implemented and recorded that the town

consisted of 600 houses, and 3,000 people. During the

17th century about £400 was paid annually to the poor of

Darlaston which shows that the welfare state is not new.

It's hard to imagine that such a large population could

have existed on agriculture, and its inevitable service

industries. By this time early industrialisation must

have started, although on a very small scale. The many

local surface deposits of coal, and the nearby iron ore

deposits must have been used in a variety of cottage

industries. The iron produced from the ore was known as

blond or blend metal, very similar to the cold shear

iron from the Cannock area. It was a good quality

product, used in nail making and for tools, such as

hammers. Some of the earliest evidence for mining in

the area can be found in records relating to

neighbouring Wednesbury. In 1315 John

Heronville, lord of the manor of Wednesbury died. John’s

widow Juliana was entitled to one third of the estate

for life (her dower) or until she remarried. The

document relating to the dower is an important record,

giving details of much of the estate. It records several

coal pits, and as such is the earliest record of coal

working in the town. Similarly it contains the earliest

record of ironstone mining in the town. |

| Darlaston is situated on part of the South

Staffordshire coalfield, where the middle coal measures

are found, which were locally known as the ten yard

seam. This forms a gently folded shallow syncline that

outcrops in a wide arc from Dudley through to Darlaston,

and actually consists of 12 to 14 closely overlying

seams, giving the appearance of a single bed of coal.

This is usually less than 400 feet beneath the surface,

and in many places can be found just a few feet below

the surface. The mineral rights belonged to the Lord of

the Manor and anyone wishing to dig for coal had to

acquire a copyhold, which was a legal document obtained

via the courts. Such surviving documents provide

evidence for early mining in the area. |

|

|

In 1698 Timothy Woodhouse was manager of the coal

mines belonging to Mrs Mary Offley, who was the Lady of

the Manor. He had a two year contract and was paid

£20.00 a year, for which he maintained the buildings,

looked after the horses, collected arrears, hired

colliers, and organised sales. In the first year he sold

3,000 sacks of coal and later went into partnership in

his own business.

Another record states that Edward Blakemore, a

nailer, had a milking cow, barley, winter corn, and

land. He was owed £30 by the Lady of the Manor, Mrs Mary

Offley for coal, and expected that his executors would

go to law to recover it. This shows that much of the

early industry was done on a part-time basis, shared

with farming.

Records do survive from 1415 which mention plots of

land lying between coalfields in Bradley. A deed of the

Perry family dated 1401 mentions two coal pits in

Bilston. One was called the Hollowaye, and the other the

Delves, both of which were situated near Windmill Field.

Camdens Brittania, published in about 1580 has this

entry:

The south part of Staffordshire hath coles digged

out of the earth, and mines of iron, but whether to

their commodity or hindrance I leave to the inhabitants

who do or shall better understand it. |

|

A typical gin pit. Large

numbers of these were in common use until the early

years of the 20th century. |

| Until the mid 18th century coal was not used for

heating in the home, it was only used for this purpose

when moss and wood became harder to obtain. Shaw, who

was writing at the close of the 18th century had this to

say about mining in the area:

There are several coal-pits sunk lately, and

probably will soon be more, as they have lately cut a

canal through the parish to Walsall. There is only one

coal mine at which they work now in this parish, in

which the coal is about 7 yards thick. The ironstone is

about three quarters of a yard thick, and is found in

the parish under the coal. The mines are very subject to

damps. The miners are subject to asthmatic complaints,

and very few of them live to be seventy years of age.

The air is sharp and dry. There is great plenty of

brick, tile and quarry clay; in some places not more

than 4 feet, and in others a great deal more. There is a

mine of clay now at work in which they have gone 13 or

14 feet deep, and it is then good. They are prevented

going deeper by water.

This is interesting, but Shaw must have been wrong in

his assertion that just one pit was at work at this

time. He also notes that the following traders were at

work in the town:

gun-lock makers, nailers,

fet makers, chape forgers, chape makers, stirrup makers,

buckle-ring forgers, and miners.

A document dated 1750, concerns a letter from

Darlaston coal mine under-manager, Joseph Lytcott to its

owner. With the aid of a map, he advises the owner, not

to sink any shafts in the vicinity of Clarke's Close,

because of the danger of meeting other workings

underground, which could cause flooding.

I think it advisable that a pitt be sunk in the

lane leading to Birmingham and that they drive a road by

the lane side along Mrs. Cookes hedge to prevent or

discourage her getting coal under the lane, for I

understand she's one that will loose nothing she can get

by any means fare or fowl. I have picked the

place in the lane as you will see between

x..............x if they sink and work in Clarke's Close

all the water in Cookes and some of Shiltons must

inevitably come upon in as you may see by the drop of

the coal, and if the road I speak on be driven to secure

Mrs. Cookes forthwith as may be done it must be while

she's working and then she will drain the water from us

- if she have any and if you approve of this I will

write to Mr. Wood to say I goe for London and call at my

coming down to see whether it be performed.

Joseph Lytcott

Clarke's Close was an area of about six acres and

contained twenty three pits, of which seven were

at work. The shafts were closely spaced as can be seen

from the sketch, at Kitchen Croft they where not more

than fifty yards apart. This is a clue to the type of

pits being worked, namely bell pits, as the limit for

underground working would have been within about a

twenty five yard radius from the shaft. The leap

mentioned in the sketch is probably a fault, and a sough

was a drain to remove water from the mines. |

The road to Birmingham is

Dangerfield Lane, the road to Bilston is Moxley Road,

the road to Wolverhampton is Wolverhampton Street, and

the church at the bottom left hand corner is Saint

Lawrence's. |

Much of the area around Pinfold Street,

particularly on the southern side was heavily

mined, as can be seen from the drawing above. In

the late 1770s one of the most successful coal

and iron producing families in the Black Country

moved there. John Bagnall, his wife Margaret and

their children moved to Pinfold Street from

Broseley. Behind their house was a piece of land

where John opened several mines. He died in 1800,

and mentioned in his will that he extracted coal in

his garden. John and Margaret's descendants founded

and ran coal mines and iron works in Wednesbury and

West Bromwich, and created a business that became one

of the area’s largest producers of coal and iron

in the first half of the 19th century.

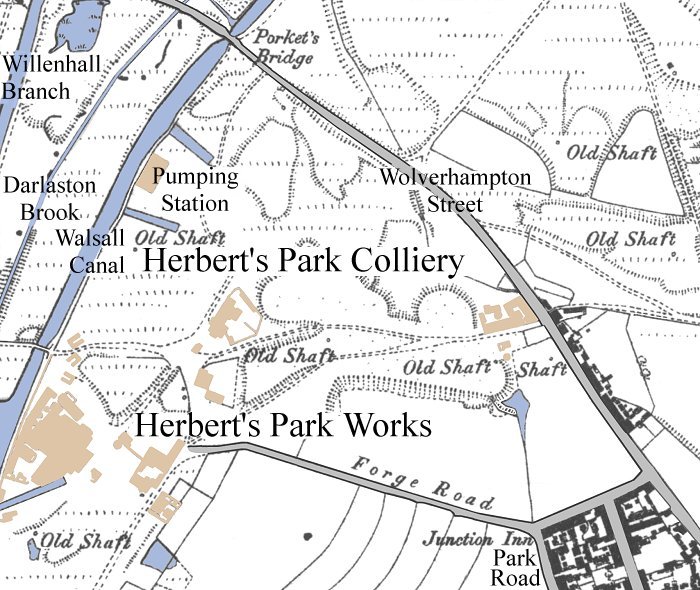

Herbert's Park Colliery, Ironworks, and Furnaces

Herbert's Park Colliery occupied the site of the old

George Rose Park, much of which is now part of Grace

Academy. The colliery covered just over 18 acres,

and was run by William Marshall, and Henry Rogers.

The minerals mined included new mine coal, fireclay,

new mine ironstone, and rough hill ironstone. In 1842

the business went into liquidation and was sold at

auction. |

|

The location of Herbert's Park

Colliery, ironworks and furnaces. |

| The bankruptcy notice in the

London Gazette:

Herbert’s Park

Colliery

To be sold at

auction by John Fellows on Thursday the

27th day of October 1842 at the Waterloo

Rooms in Waterloo Street, Birmingham, in

the county of Warwick, at twelve o’clock

at noon precisely, pursuant to an Order

of the Court of Review in Bankruptcy,

and by the direction of the assignees of

William Marshall and Henry Rodgers,

bankrupts, free from auction duty, and

subject to conditions to be then and

there produced.

All that undivided

moiety, or equal half part, or other the

part share, estate and interest of the

said bankrupt, William Marshall, of and

in those sic closes, pieces or parcels

of land, known by the name Herbert’s

Park, with the mines and minerals now

remaining un-gotten in and under the

same, situate in the Parish of

Darlaston, in the county of Stafford,

containing by measurement, 18 acres, 16

perches, or thereabouts, and in part

bounded by the Birmingham and Walsall

Canal.

The new mine coal,

the fireclay, the new mine

ironstone, and the rough hill ironstone

have been proved. Several pits or shafts

are sunk in the land, and a winding and

pumping engine for getting coal, and two

winding engines for getting ironstone,

are now standing thereon.

For further

particulars apply to Messrs. Mallaby and

Townsend, Solicitors, Liverpool; Messrs.

Stubbs and Rollings, Solicitors; or to

the Auctioneer, of Birmingham.

|

|

| In the list of owners and occupiers that

accompanied the 1843 tithe map of Darlaston,

the colliery is listed as belonging to

Messrs Taylor & Company, but David Jones

soon purchased the colliery and

built Herbert's Park Ironworks. Within a few

years there were fifteen puddling furnaces,

two blast furnaces, and a narrow gauge

tramway to the coal mines. On 12th June,

1851 there was an explosion at the works. It

is mentioned in 'A History of Mining in the

Black Country' by T. E. Lones, 1898.

From

1875 to 1880 Herbert's Park Colliery is

listed as being owned by David Jones & Sons,

then in 1885 by Thomas & I. Dowen, and

from

1915 to 1918 by Samuel Weaver. It seems that

the colliery had ceased to be used by the

late 1880s. It is marked as disused on the 1889

Ordnance Survey map. |

|

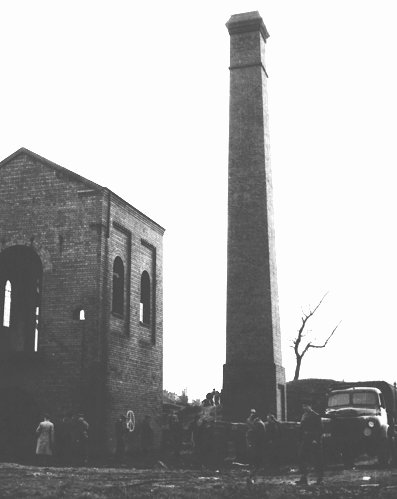

The demolition of the

pumping station chimney in the 1960s. |

On the left is the old pumping engine that

pumped water out of the colliery, into the

canal. It stood beside the canal until

demolition in the 1960s. I remember it as a

child, when it contained a beam engine. |

Some of the larger pits in 1869 were as follows:

| Colliery |

Owner |

| Albert Colliery |

David

Rose |

| Bescot Colliery |

Darlaston Steel and Iron Company |

| Darlaston Green

Colliery 1 |

James

Sanders |

| Darlaston Green

Colliery 2 |

George

Oates |

| Greens Farm

Colliery |

Greens

Farm Colliery Company |

| Herberts Park

Colliery |

David

Jones |

| James Bridge

Colliery |

J.

Bagnall and Sons |

| North-western

Colliery |

J.

Simpson |

| Rough Hay Colliery |

Addenbrooke and Co |

| Victoria Colliery |

John

Dutson |

Darlaston pits in 1880 included:

| Colliery |

Owner |

| Bull Piece |

G.

Spruce. |

| Broadwaters |

David Rose |

| Russian

Colliery |

David Rose |

| Darlaston

Green |

Price and Company |

| Darlaston

Green |

James Saunders |

| Heathfield |

J.

and J. Cotterill |

| James Bridge |

J.

Bagnall and Sons |

| King's. Hill |

Bayley and Hunt |

| King's. Hill |

Joseph Springthorpe |

| Rough Hay |

Simpson and Company |

| Rough Hay |

Butler and Company |

| Rough Hay |

Bargwin and Company |

| Rough Hay |

Joseph Baugh |

| Rough Hay |

Williams and Company |

| Moxley |

Evans and Collis |

The larger pits in 1896 were:

| Colliery |

Owner |

| Moorcroft

Colliery 1, Moxley |

Moorcroft Colliery Company |

| Moorcroft

Colliery 2, Moxley |

G. W. Bray |

| Moxley

Colliery |

Jacob Chilton

|

| Rough Hay

Colliery |

S.

Yates |

| Woods Bank

Colliery |

Hewitt and Company |

| Woods Bank

Colliery |

James Cotton

|

| Heathfield

Colliery |

George Lester |

|

| Another colliery, Mill Colliery, was in Mill Street.

It was a deep pit into which sand was pumped for several

weeks in the mid 1950s to prepare the ground for the

building of the row of shops and the flats in

Catherine's Cross. It was named after Darlaston windmill

in Dorsett Road.

The Bell pit method of mining involved digging

outwards from a central shaft in many directions, until

the roof was in danger of collapsing. The pit was then

abandoned and another dug. Sometimes a pair of shafts

would be dug about 50 yards apart and joined by an

underground passage in order to allow circulation of

air. The coal would then be removed from the sides of

the connecting passage. This very wasteful technique

could be employed because coal was so plentiful and

easily obtainable. Later when larger pits were dug,

columns of coal were used to support the roof instead of

wooden props, and so many tons of coal must have been

lost in this way. Most of the mine companies were very

small, owning just one or two pits.

|

A typical bell

pit. The shaft is dug down to the layer of

coal and the spoil is removed in a bucket

that is wound up and down the shaft by a

windlass. When the coal is reached the sides of the

shaft at the bottom are widened as the coal

is removed. This process continues until the

shaft is in danger of collapsing. The pit is

then abandoned and a new one dug nearby. |

The shafts would eventually collapse or be filled-in

with spoil from nearby workings. Eventually little

hollows would form above the shafts. These hollows could

be found on much of the open land in the Darlaston and

Bentley area, until the building projects of the 1960s

and 1970s removed them forever. |

| The clay beds gave rise to the

local brick and pot industry. These deep excavations and the

many mining spoil heaps have sculpted the Darlaston

landscape, which is now very different to how it

used to be. Popular sporting activities in the 17th and 18th

centuries included dog fighting, cock fighting and bull

baiting. In the 18th century coins were in short supply

and several trade tokens were made for general

circulation. The one below was produced by miller and

bread maker J. Huskins of King Street. |

Darlaston had at least one windmill. Morden's

map of 1695 shows a windmill on the brow of the hill

near the top of Dorsett Road.

| |

|

Read about

Darlaston Windmill |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Early

Historical References |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to Nail

& Clock Making |

|