|

Nail Making

In 1710 Darlaston had 23 nail makers. By

this time nail making had become extremely simple due to

the invention of the slitting mill in 1565. This

prepared iron rods for the nailers, so that all they had

to do was to cut the rod to the correct length, point

one end, and make the head. This was one of the first

examples of mass production, as large quantities of

nails could be made simply by unskilled people. The

nailers couldn't afford to buy the rods themselves, they

were advanced to them by the mills, to where they

returned the completed nails and were paid for them.

They were also given standard allowances for waste.

Nailing was a seasonal occupation and dealers spoke of

the difficulty of obtaining nails at harvest time. About

the end of the 18th century this began to change as

factories appeared employing large numbers of

wage-earning people. A bundle of rods weighed 60 pounds

and was 4ft 6" long. The nails were characterised

according to the number produced from a given weight of

iron. Long thousand (1,200) nails weighing 4 pounds,

were known as four penny bundles. Larger nails were

called 100 work, and were priced by the hundred. They

were more profitable than the smaller ones, as less work

was required to produce them, and less waste produced.

There were many types of nails including:

brads,

tacks, spriggs, dog-eared frost nails, sheath nails, and

sparrables

Most of these types go back to the early

16th century. The introduction of machine nailing in

1810 led to a further increase in the numbers of people

employed in the industry, but in Darlaston the last nail

manufacturer had closed by 1888 due to the preference

for light engineering. Even by 1818 such diverse iron

products as fire irons, bullet moulds, thumb latches,

and handcuffs were produced here.

Clock Making

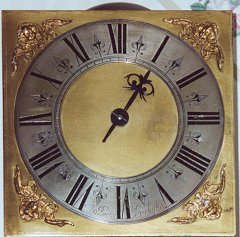

In the 18th century there were several highly

skilled Darlaston clockmakers producing long case clocks

to a very high standard. The photographs below show some

of the wonderful clocks that they produced. |

|

This example was made by D. Hawthorn in about 1705.

It has a 12" brass dial with silvered chapter ring,

minute and quarter hour gradations, and is housed in a

fine walnut case. |

| This fine hoop and spike clock was made by Thomas

Brewer in about 1750. It has a 10inch dial with cherub

spandrels, and strikes on the hour.

Photo: Laurence Cook.

|

|

|

Thomas Brewer's name as inscribed on the clock's

chapter ring.

Photo: Laurence Cook. |

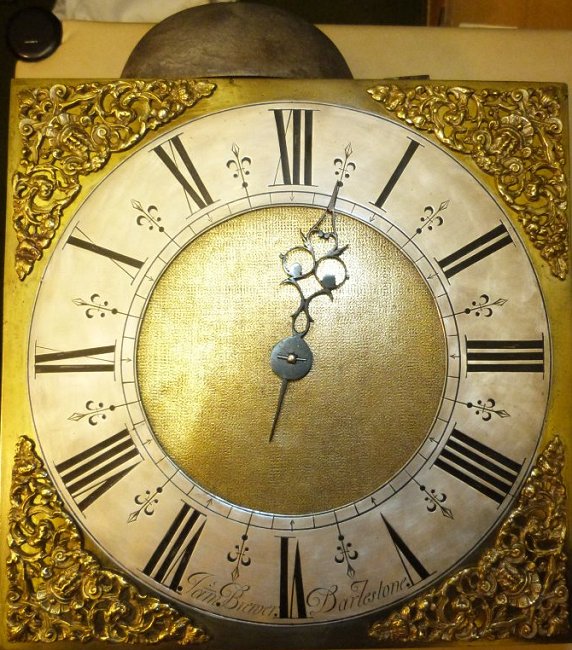

| Another fine Darlaston made clock that is

inscribed "Jam Brewer, Darlistone". It

was made by James Brewer who may have been a

relative of Thomas Brewer.

Photo: |

|

|

A close-up view of the face of the

James Brewer clock.

Photo: |

The inscription on James Brewer's clock.

Courtesy of Stuart Cooper. |

|

|

|

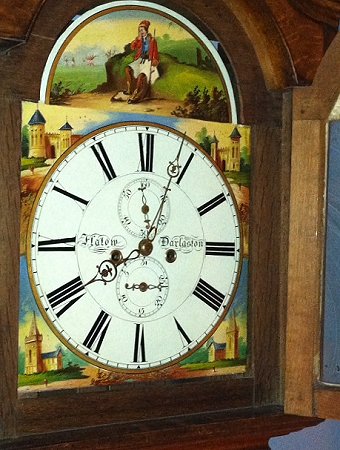

| This is another fine example of

a Darlaston-made clock. The lucky owner is

|

|

|

This clock carries the name Banks, Darlaston. It was

produced by George Banks who is listed in the 1818

edition of the Staffordshire General & Commercial

Directory, and the 1828 and 1842 editions of Pigot &

Company's Commercial Directory as a watch and clock

maker, in Church Street. He is listed identically in

White's 'History, Gazetteer and Directory of

Staffordshire', both in 1831 and 1851.

He was also the town's postmaster, and ran the town's

first post office from his premises in Church Street. He

is listed as such in White's 1851 edition of his

History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire.

He does not appear in any of the later directories.

In 1861 the postmaster was Henry Wright, so he had

possibly retired by that date. |

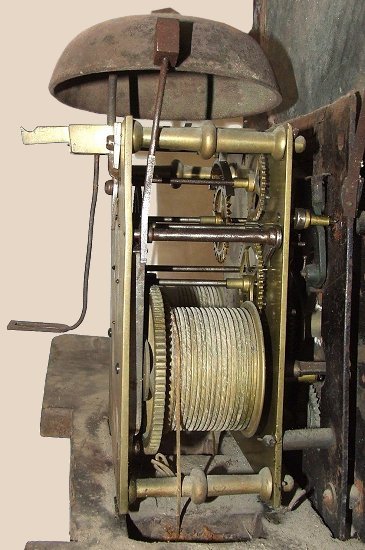

| A view of the clock mechanism. It appears to be a

standard mechanism that was widely used, so maybe George

Banks purchased the mechanism, the dial, and possibly

the case. Equally he could have purchased the whole

clock and had his name painted on the dial. |

|

|

A final view of the clock. |

This photo of a fine example of a George Banks'

clock was kindly sent by Sean Quinn of Decorative Arts,

Waddington's Auctioneers, 275 King Street East, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada.

It has been described in their catalogue as an English

oak and mahogany tall case clock, by George Banks,

Darlaston, from the first half of the 19th century.

It has an enamelled dial in a traditional case with

Tunbridge and shell inlay, the trunk is flanked by ring

turned columns. The clock is 94 inches high.It is not

known if this is the original case for the clock. It was

included in a sale, and surprisingly didn't sell when

offered for $500 CAD (about £290). |

|

|

The finely painted clock face. |

|

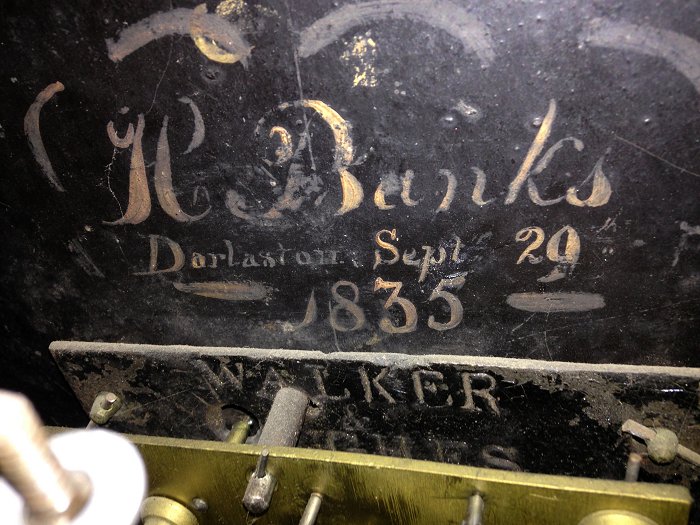

A close-up view showing the

maker's name. |

The back of the dial on the clock

above carries the customer's name and date, and the

false plate, the fixing plate for the dial, carries the

dial maker's name, which is Walker & Hughes of

Birmingham. Courtesy of Sean Quinn. |

John Kelk's fine clock made by

James Brewer. John mentioned that James Brewer is

listed in Britten's

“Old Clocks And Watches And Their Makers” as being a

clockmaker of Darlaston who died in 1756. The clock

has a 30 hour movement with strike and single hour

hand with a 10 inch dial. John has dated his clock

between 1730 and 1740. |

|

A close-up view of the maker's

name on John Kelk's clock. I must thank John for his

help with this section. |

|

Another example of a fine clock made in

Darlaston. The maker was J. Blunt. The dial

was produced by

Walker

and Hughes.

The photographs

were kindly sent by the owner of the

clock, Jane Hartnell, who mentioned that

Walker and

Hughes were in business between 1812 and 1835,

which is an indication of the age of the clock.

If you have any

information about J. Blunt, please do

send me an

email.

|

|

Another view of

Jane

Hartnell's lovely clock. |

| If anyone has any information on these or other

Darlaston clocks, or clockmakers, please

contact me

and I will be delighted to hear from you. |

|

|

|

Return to

Early Growth |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to

Churches & Chapels |

|