|

Years Of Growth

The gun trade became well established in the 18th

century, employing about 600 people in the manufacture

of gun locks and barrels. These were mainly supplied to

the gun manufacturers in Birmingham, and brought great

prosperity to the town. During the Napoleonic and

Burmese wars guns were in great demand. The trade was

very much a family craft, the skills being handed down

from father to son. Gunlock makers usually supplemented

their income by doing other types of work, because the

gun trade suffered from periods of depression. A typical

worker was John Stokes who was also licensee of the Old

Castle Inn in Pinfold Street, later known as The Old

Castle Hotel. There were a number of families in King

Street that were involved in this trade, including the

Golchers, the Williams, and the Josephs.

|

|

A typical Darlaston gunlock

workshop. |

In the late 1750s there were 300 to 320

gunlock filers, 50 to 60 gunlock forgers, and 250 boys

employed as filers, gunlock forgers, cock stampers, and

pin forgers.

A 14 hour working day was usual with the

truck method of payment often being used. This involved

payment in kind with food or fuel. During the Napoleonic

wars the Birmingham gun trade supplied over 3 million

gun barrels, and 2.8 million gunlocks to the British

Government. The largest recorded production in a single

year was 490,838 gun barrels, and 457,616 gunlocks, in

1813. |

|

After the end of the Napoleonic wars in

1815 the demand fell and Darlaston went into a severe

depression, which lasted until 1839. The remaining trade

was mainly confined to the export market and sporting

guns. The development of machine made locks virtually

eliminated the trade in Darlaston by about 1870. In

Birmingham a smaller trade for hand made sporting guns

continued until the early 1920s, but the manufacturers

tended to make all of the parts themselves, so it was of

no benefit to Darlaston. The last known workshop in the

town was a two storey building that was just to the left

of the present public library in King Street. It was at

the rear of Appleyard's shop and demolished in the early

1970s when the library was built.

Parson & Bradshaw's Directory of 1818

lists the following products that were manufactured in

Darlaston:

| bridle bits,

buckles, bullet moulds, carpenter's tools,

dog collars, files, fire irons, guns,

gunlocks, handcuffs, harness buckles, hasp

locks, nails, padlocks, trunk locks. |

The 1801 census includes the following

information about the population of the town:

|

Population: |

3812 consisting of

1996 males, and 1816 females. |

|

Housing: |

703 inhabited

houses, occupied by 777 families. 59

uninhabited houses. |

|

Employment: |

1325 people

employed in trade, manufacturing, and

handicrafts.

2452 people in other employment. 35 people

working in agriculture. |

| |

|

| View a

commercial and trade directory from 1818 |

|

| |

|

Darlaston's depression resulted in a

great increase in the number of poor people in the town,

who were helped by payments from local taxes, which were

raised from the middle and upper classes. Many tax

payers believed that they were paying for the poor to be

lazy and so they often complained to the powers that be.

In 1834 a new Poor Law was introduced to reduce the cost

of looking after the poor. Under the terms of the new

law, parishes were grouped into unions, each of which

had to provide a workhouse where the poor could go to

get help. Once in the workhouse they would be made to

wear a uniform, obey the strict rules and regulations,

and work hard.

It is interesting to compare the amount

of poor relief paid in the local towns as a way of

comparing their individual fortunes at the time:

| |

Population

in 1831 |

Total relief 1834-35 |

Total relief per

head of population |

Total relief

1835-36 |

Total relief per

head of population |

|

Darlaston |

6,600 |

£1,251 |

3s.9d. |

£1,453 |

4s.5d. |

|

Wednesbury |

8,000 |

£1,892 |

4s.8d. |

£1,733 |

4s.3d. |

|

Walsall |

14,000 |

£4,409 |

6s.3d. |

£3,714 |

5s.4d. |

|

Willenhall |

5,000 |

£1,075 |

4s.4d. |

£1,028 |

4s.1d. |

|

Bilston |

14,000 |

£3,843 |

5s.6d. |

£2,816 |

4s.0d. |

|

Tipton |

14,000 |

£3,090 |

4s.5d. |

£2,868 |

4s.0d. |

West

Bromwich |

15,000 |

£3,128 |

4s.2d. |

£2,397 |

3s.2d. |

In 1835-36 a lower percentage of people

were receiving poor relief in West Bromwich than in the

other towns, but only Darlaston saw an increase in

payments.

The middle of the last century was at

last a time of growth for Darlaston. After the

opening of the railway, Darlaston's manufacturers went

from strength to strength, greatly increasing the town's

prosperity. A commercial directory of 1851 lists 35 nut

and bolt manufacturers in the town, the large number

being solely attributable to the presence of the

railway.

A report produced by the Children's

Employment Commission in 1843 gives an insight into

what life was like for children and young people in

Darlaston during the early 1840s. The following extracts

are descriptions provided by Charles Thornhill, Charles

Green, and Isaac Clarkson in 1841:

|

|

The

Condition of Children and Young Persons in

Darlaston in 1841

Charles Thornhill, Esq.,

aged 34, Surgeon to the Darlaston and

Bentley district of the Walsall Union:

Has practised ten years in Darlaston; has

had continual opportunities of observing the

treatment and condition of children and

young persons of the working classes, both

in mines and manufactories; can bear

testimony to the fair treatment they

uniformly received from their employers;

they are well fed, well clothed, and for the

most part healthy; is not aware of disease

peculiar to them; they are as healthy as the

children of the adjoining places; would

especially refer to the good treatment of

the apprentices of the miners in this place;

the apprentices of the butties generally

present a very fine physical appearance.

Of their mental and moral

condition, not much good can as yet be said,

but 'there is an attempt at education among

them, and even a great interest displayed in

it by the butties. The number of schools

here is considerable, and the attendance

very large; but the masters and teachers are

not efficient; they have never been trained

in any way beyond that of the schools they

attend, in which, they themselves were

educated. Has noticed the bad ventilation of

some school rooms; would except the national

school of the established church, and a

school room which is spacious and of good

height, such as that of the British school.

Hernia exists here among the

boys, but not to any great extent; considers

it far more prevalent in some of the

adjoining parishes, Willenhall in

particular; attributes its existence in

these parts of the country to over-exertion,

such as lifting heavy weights and drawing

loaded skips of coal, lime, and ironstone.

Thinks among the women there is not much

malformation of the pelvis; labours are

generally easy, but at the same time there

are more than the average number of

preternatural presentations, and instruments

are frequently employed; there are a number

of cases in which haemorrhage occurs;

attributes these circumstances to the fact

of the women winding almost the whole day at

windlasses on pit banks, in screw

manufactories, etc., and to their carrying

heavy weights on their heads, particularly

of coal, which the colliers families are

allowed to have gratuitously, as much as

each carry at a single load a day; each one,

therefore, carries away the utmost possible

to her.

Bronchocele and calculous

diseases prevail here; attributes them to

the water of the neighbourhood, which is

strongly impregnated with the salts of lime

and ironstone. Asthma is also common to

those who have long worked in the pits,

arising from the minute particles of dust

floating in the atmosphere of the pit; and

from the miners catching cold upon cold.

Water abounds in some pits to a great

extent, and the miners work all day in the

wet; this frequently causes a number of

boils to arise in different parts of the

body which come in contact with the water.

Fever is not more prevalent

here than in other parts of the country; but

when it does break out, the cases are of a

virulent kind, and of long duration. These

cases originate in most filthy parts of the

parish, where there is no underground

drainage, where accumulations of filth

abound on the surface. The women here of the

working classes are very prolific, many of

them having a child every year. It is a

common thing here for a woman to have from

nine to twelve children. The number of

illegitimate children is great, many of the

girls having had from three to four each;

there is scarcely any prostitution in the

place, though the inhabitants are numerous.

The young men and women of the working

classes are so constantly associated

together in work-shops, manufactories, and

on the pit banks, at nearly all towns, as to

supersede all prostitution; the improvidence

and want of management among the working

classes is very great; they are as

extravagant as possible whenever they get

the means; many of them will have large

joints of meat on Sundays and the earlier

part of the week, and be in almost a

starving condition by Friday and Saturday;

there is much drunkenness here in the early

part of the week when trade is good; the

women are great smokers.

Charles Thornhill

Mr. Charles Green, aged 62, Malster and

Farmer:

Has lived in Darlaston 28 years. Apprentices

formerly were badly treated by some masters,

ill clothed, and ill fed; and beaten

unmercifully, but in rare cases; they were

in those cases parish apprentices obtained

from other parishes, such as Lichfield,

Stratford, Coventry; at that time there was

some premium given with each apprentice, £4

or £5, and always a suit of clothes.

When the master had got

the boys or girls with the premium, they

cared nothing about them, and would have

been glad if they had been burnt or drowned

to have got rid of them. Thinks it is very

little the case now; thinks the children are

now well fed and well clothed, and not

improperly punished, almost generally;

thinks money is not given now with

apprentices, except from charities left for

that express purpose, which has thus become

abused.

There is a great lack

of education here, or of the wish for it on

the part of parents and masters; there is

much more desire than there was, but far

from a general desire; the Sunday schools

are largely attended, particularly among the

Methodists; believes the teachers are very

incompetent for such an office.

Charles Green

The Rev. Isaac

Clarkson, Vicar of Wednesbury:

Stated, that in his capacity as magistrate,

complaints often came before him, made by

boys against; masters from different places

round about, such as Willenhall and

Darlaston, but he did not encourage them, as

they should more properly apply to the

magistrate of Wolverhampton.

More complaints came

before him from the mines than from the

manufactories; but sometimes there was very

bad usage in the latter. A boy from

Darlaston has recently been beaten most

unmercifully with a red hot piece of iron.

The boy was burnt, fairly burnt. Wished to

cancel the indentures, but the master had

been to the Board of Guardians, or to the

Clerk of the Stafford Union, and promised to

behave better in future. Has various similar

cases brought before him.

A great number of the

small masters are not fit to have

apprentices. Says this with reference to

Darlaston and Willenhall; nothing of that

kind occurs in Wednesbury, except sometimes

in the mines. The number of complaints are

very few from Darlaston; they are mostly

from Willenhall.

Isaac Clarkson |

|

| |

|

View an early

Darlaston map |

|

| |

|

| The gunlock makers were skilled and resourceful

people. Many of them turned their hands to other

industries, using their metal working skills. By the

1830s the town had a number of small factories producing

a wide range of products including buckles, buckle

tongues, coach harnesses, files, fire irons, hinges,

latches, locks, screws, and stirrups. There were also

iron founders, and stampers. The Carter family, who

lived in Great Croft Street were ex-gunlock makers who

had seven workshops behind their house. They invested in

up-to-date plant and machinery, which included a steam

engine to drive their machines and presses, presumably

by overhead line shafting and belts. There were several

employees, including five apprentices.

|

The location of Great

Croft Street, which became part of St. Lawrence

Way. |

The business is listed in several trade directories:

The Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory

for 1818

Carter, William stirrup, snaffle,

and girth buckle maker, Great Croft Street

Carter, James stirrup and bridle bit maker, Great Croft

Street

Carter, William roller buckle manufacturer, Croft

Street

Pigot & Company's National

Commercial Directory of 1828

Bit and Stirrup Makers

James Carter, (and pattern ring). Great Croft Street.

Bolt and Latch Makers

James Carter, (screw). Great Croft Street.

Boot & Shoe Heel and Tip Makers

John Carter. Great Croft Street.

Patten Ring Makers

William Carter and Son. Great Croft Street.

Stampers

James Carter. Great Croft Street.

William Carter and Son. Great Croft Street.

William White's 1831 Gazetteer

and Directory of Staffordshire

William Carter & Son, Great Croft

Street, bolt and Norfolk latch makers, stampers

(gunlocks), boot and shoe heel tip manufacturer.

James Carter, Great Croft Street,

bolt and thumb latch maker, stirrup maker, boot and shoe

heel tip manufacturer.

Pigot & Company's Directory of

Staffordshire, 1842 (The business was actually sold

in December 1841)

Bolt and Latch Makers

Carter, James. Great Croft Street.

Carter, William & Son. Great Croft Street.

Boot & Shoe Heel and Tip Makers

Carter, William & Son. Great Croft Street.

Unfortunately a terrible accident

took place on Monday 22nd January, 1838, when the boiler,

which fed the steam engine exploded.

Boiler Explosion

The boiler explosion at Carter's

works was reported as follows: |

|

Staffordshire Examiner 27th January, 1838

Explosion. On Monday

morning, about half past ten o'c1ock, the steam

engine boiler, in the extensive shoe heel tip

and spoon manufactory of Messrs. Carter and Son

in Great Croft Street, Darlaston, exploded with

a tremendous noise, which alarmed the whole

town, and was heard distinctly at a distance of

a mile and a half. The inhabitants in the

neighbourhood were astounded, and many who had

no faith in the millennium pronounced the world

to be at an end. The top of the boiler, ten feet

diameter and seven feet high, weighing a ton and

a half, was torn from its situation and forced

upwards at least fifty yards, descending upon an

angle at a house in Cock Street, one hundred

yards from the factory, breaking a small portion

of the roof, and from thence, rebounding into

the street, rolling against a house opposite,

shattering the doors and window shutters, and

forcing the brick jamb a little out of the

perpendicular.

Had the boiler in the first

instance fallen one yard further, the house must

have been destroyed; or if when in the street it

had rolled another half foot, the second house

would have been stove-in, and must have fallen.

Several pieces of cast iron pipe were found in

Mr. Rooker’s garden and yard in King Street, 150

yards from the scene of accident, one of which

knocked down a fence wall, and so shook the part

of the house adjoining as to admit the light

through the joints of the brickwork.

Bricks were plentifully

scattered over all the yards and streets within

a hundred yards, and yet, most miraculously, not

a single individual was in the least injured

(except a boy who was oiling a part of the

machinery, and who was thrown by the concussion

of the wind against the cylinder, and slightly

bruised on the back of his head) although the

accident occurred in the centre and in the most

thickly populated part of the parish.

A clump of more than fifty

bricks passed directly over the head of a man in

the service of Mr. Thomas Bailey, who was

putting a horse into a cart, and fell five or

six yards beyond him: neither man nor horse were

hurt, although both were terribly frightened.

Several shops belonging to the Messrs. Carter

were partially destroyed, but the damage done is

not so extensive as was at first supposed. It

may appear incredible that the boiler was forced

so high into the air, but several persons who

witnessed its ascent affirm that it was

considerably higher than the steeple of the

church, which is 140 feet. |

|

|

Courtesy of

Peter Carter, James Carter's great, great, great,

grandson. |

|

Sheffield Iris. Tuesday 30th January, 1838.

Explosion of a steam boiler at Darlaston

On Monday last, the

boiler attached to the manufactory of Mr.

Carter, at Darlaston exploded with great

violence. The boiler itself, weighing

upwards of two tons, was carried over the

adjoining houses, and fell in Cock Street, a

distance of 150 yards, doing considerable

damage to two houses in its descent.

It first fell upon a

house on the north side of the street,

occupied by a shoemaker, demolishing a

portion of the roof and the gable end; and

rebounding from thence, fell against a house

on the opposite side of the street, knocking

in the door and a portion of the wall. About

a yard of the steam piping was carried forty

yards further, and propelled against the

house of Mr. Rooker; and falling from

thence, broke down an adjoining wall.

Another part of the piping was blown through

the front window of the same house. The

bricks etc. were scattered in all directions

for one hundred yards, and so great was the

conclusion that most of the houses in the

place were somewhat shaken. Three of Mr.

Carter’s shops were entirely blown down

The accident is mainly

attributable to the intense frost of the

previous night having frozen down the safety

valve. We are happy to say that not a single

individual sustained the least personal

injury, though the escape of several was

almost miraculous. |

|

|

Courtesy of

Peter Carter, James Carter's great, great, great,

grandson. |

| It is amazing that no one was killed, and that

little damage was done. The business, and family

houses in Great Croft Street were sold at auction in

the White Lion pub on Friday 3rd December 1841.

James Carter moved to Blakemores Lane, where he died

in 1843. The family went on to open a large factory

on King's Hill, and later at James Bridge.

An expanding Town

As the population increased in the middle of the

19th century there was a demand for more houses and

so areas around Blockall, The Green, and Catherine's

Cross were developed, usually where little land

reclamation was required. One of the new streets

built off Catherine's Cross, on the northern side of

the Russian Colliery in the 1850s was Foundry

Street, named after nearby Phoenix Foundry, in

Catherine's Cross. |

|

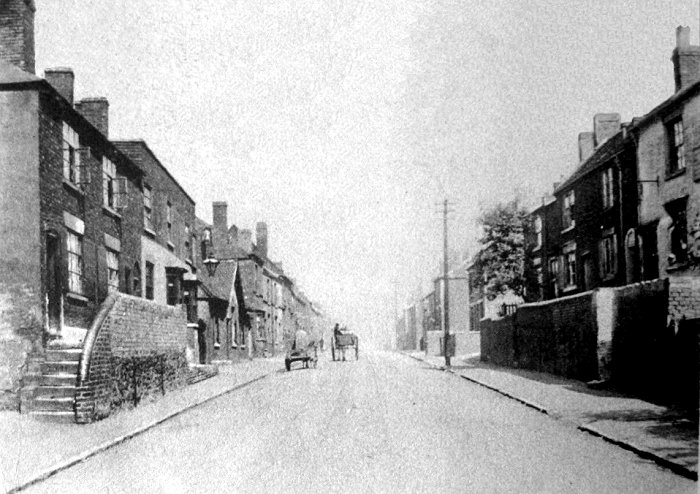

The western end of

Foundry Street. |

Foundry Street, which was demolished in

1955 has completely disappeared. It was

replaced by the three storey blocks of

council flats in Park Street. Phoenix

Foundry was founded in 1830 by John

Garrington to produce forged components for

the gun trade. |

| In 1879 the firm moved to Albert Works

in Willenhall Road. In 1851 part the factory

was occupied by Thomas Wood, as can be seen

from the advert below. |

|

King's Hill. From

an old postcard. |

|

The Moxley Rope Works Company Ltd. was formed in

1849, to manufacture ropes for the coal mines. The ropes were made from locally grown flax, but

were rendered obsolete by the invention of the

rattlechain, and later wire rope. As the mining industry

declined, the company started making rope slings, plough

reins, and boat lines. When steam engines became

plentiful, plaited gaskin (packing) was developed.

Gaskin remained in production for the joining of salt

glazed drain pipes, but the main products were lorry

sheets, made from jute canvas and cotton flax, lorry

ropes, and slings for lifting tackle. |

One of the few natural resources that hadn't been

exploited were the deep clay beds that lie along the

Darlaston - Moxley boundary. The clay was first used

commercially by the Moxley Brickworks, which was owned

by the Wood family, who were large landowners in the

Moxley area. Luckily the canal runs through the middle

of the clay beds, so offering easy transportation for

the finished bricks. The works were situated on what was

called The Moxley Sand Beds, off Moxley Road. A short

spur was built from the canal, which ran directly into

the works to facilitate the loading of canal barges.

Moxley Road was previously called Woods Bank, which was

named after the Wood family.

The report by the Children's Employment Commission of

1864 includes a description of the girls who worked at Woods Darlaston

Brickyard:

|

In this yard the

girls had to carry the clay up a steep

rise of about 12 yards in 50 yards.

Mr. J. Swindley,

currier, Freeth Street, Oldbury:

I have lived in the

town 30 years. I am well acquainted with

the habits and condition of the girls

employed in the brickyards. The

employment of young females at this work

is looked upon as a shame by all us

tradesmen. The girls have to do men's

work along with the men. I have often

been shocked to hear the language and

indecent talk among these girls when at

work.

After their work is

over, which is generally about six

o'clock, they dress themselves in better

clothes and accompany the young men to

the beer shops. They are a good deal in

habit of spending their earnings in beer

shops with the men. They are ignorant of

all household work, and quite

uneducated. |

|

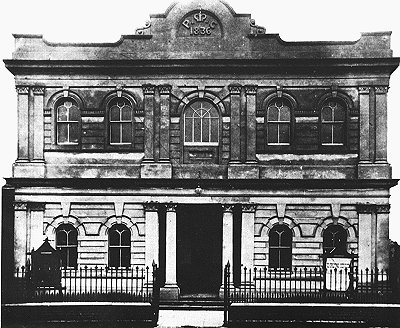

The ever expanding population led to more churches, and

a new cemetery. In 1837 the Primitive Methodist Chapel

was built in Bell Street. It replaced a meeting house in

Blakemores Lane, that had been used by the Darlaston

Primitive Methodists since 1814. The building could seat

1,200 people, and was enlarged in 1879. It fell into

disuse in 1908 after the building became unsafe due to

subterranean coal fires, which caused the walls to

crack. The congregation moved to the new chapel in

Slater Street, which opened in 1910. |

| The building was sold in 1910 to a London company,

to be used for the Darlaston Skating Rink. This never

materialised, but in 1912 the same company opened the

Olympia Cinema here instead. The entrance to the cheap

seats was in Bell Street, and the entrance to the more

expensive seats was in Blockhall. The building still

suffered from underground fires, with copious amounts of

sand being thrown down to minimise the effects.

Eventually the cinema's floor had to be replaced with

concrete, but due to the fires, the building was far too

warm in the summer. |

Bell Street Primitive Methodist

Chapel in about 1886. |

| It closed in 1956 and was demolished a few years

later. Also associated with the Primitive Methodist

Chapel was the Primitive Methodist Sunday School in

Willenhall Street. This closed around the same time

as the chapel, and became Darlaston's one and only

theatre, the Queen's Hall, popularly known as the

Blood Tub because each play usually included at

least one murder. |

|

The fine Anglican mortuary chapel

that stood in James

Bridge Cemetery. |

|

An end view of the Anglican

mortuary chapel. |

By the late 1850s Darlaston's main graveyard in Cock

Street was rapidly running out of space for burials and

something urgently had to be done. In 1853, 1855, and

1857 Acts of Parliament were passed that allowed

municipal authorities to build and run their own

cemeteries.

The newly formed Darlaston Local Board considered the

problem of overcrowding in Cock Street graveyard and

decided to build a municipal cemetery on a piece of

waste land in-between Bentley Mill Lane, the Walsall

Canal and the London & North Western Railway. |

| The cemetery cost around £4,000 and initially

covered about 4 acres. It opened in 1860. The first

burial, that of Henry Smith, took place on 22nd March. A

further four acres and a perimeter wall were added in

1887 at a cost of £2,000. Over the years the cemetery

has expanded to cover all of the available land and is

now full, no new burials being allowed. A fine Sexton's

house (Cemetery Lodge) was built, that's still there

today. It was empty for some time in the 1980s but is

now occupied and well cared for. There were two mortuary chapels following standard practice at the time, one

for Anglicans and one for Nonconformists. The Anglican

chapel survived until recent times, but the Nonconformist chapel

closed in 1945 after falling into a bad state of repair

and was demolished in 1948. |

|

The entrance to the mortuary

chapel. |

|

The rear of the mortuary

chapel. |

|

Another view of the mortuary

chapel. A fine building. |

|

A final view of the Anglican

mortuary chapel. |

|

The site of the mortuary

chapel in 2018. |

| By the late 1920s the old graveyard in Cock Street

was very dilapidated and had been vandalised. The Rubery

Owen company paid for its refurbishment, and seats were

added to turn it into a garden of rest. It opened in

1932 and was

dedicated to the late Mr. A. E. Owen, but in recent

times the burial ground fell into disrepair. The

graveyard has now been refurbished and is sandwiched

in-between St. Lawrence Way and ASDA. |

| Cock Street

Graveyard as it is today. Cock Street ran

along the right-hand side of the site. |

|

| |

|

Read the Darlaston section

from Harrison, Harrod & Company's Directory and

Gazetteer

of Staffordshire, published in 1861 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Return to The Grand

Junction Railway |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to

Industries |

|