|

The town in the late 1930s

Living conditions for the average

Darlaston family had greatly improved since the end of

the First World War. The cramped housing conditions in

the early 1920s had almost become a thing of the past

thanks to the council’s municipal housing schemes. Large

numbers of council houses had already been built to the

south of George Rose Park and at Rough Hay.

Employment

was plentiful, the larger factories had recovered from

the recessions in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and

were working flat-out. Shops of all kinds could be found

in King Street, Pinfold Street, and Church Street,

providing all of a family’s weekly needs. There were

plenty of good schools, and places to go in the evening,

in the form of cinemas, pubs, and work’s social clubs.

Life in the town was better than ever, and people were

generally happy and contented.

The onset of war

To many people war seemed

inevitable. Bad news continued to come from Germany,

where Hitler clearly had his own vision of the world to

be, and showed no sign of wishing to compromise his

plans.

On 31st March, 1937 Britain and

France guaranteed to defend Poland from any attempted

invasion by Germany, which had been interested in

acquiring the country for some time. The Poles greatly

distrusted Hitler and his motives, after a long dispute

over the ownership of a strip of Polish land known as

the Polish Corridor, which ran alongside the German

border. In 1938 alarm bells sounded when Germany invaded

Austria, and sounded again in March 1939 when Germany

took over Czechoslovakia. |

|

|

|

|

A

government booklet from March 1938. Courtesy

of Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

|

On 1st September, 1939 Germany

invaded Poland, so war was now unavoidable. Two days

later Neville Chamberlain declared war with Germany.

The initial effects on family life

Most people were not surprised when

war was declared. A feeling of comradeship in the face

of adversity prevailed, along with the determination to

do all that was necessary to support the country in

winning the war. The first major impact on local life

occurred in October 1939 with the introduction of

conscription. The government announced that all men

between the ages of 18 and 41, who were not working in

reserved occupations, could be called to join the armed

forces. They would receive their call-up papers in the

post, which included details of where and when they had

to attend a medical, and begin military training.

|

| |

|

Read about

conscription |

|

| |

|

|

Employment was plentiful and

people worked long hours to support the war effort.

At the outset of war, factories came under the

control of the Ministry of Supply, a department set

up to coordinate the supply of essential arms,

ammunition, and equipment for the armed forces.

Large amounts of weapons,

tanks, military vehicles, and equipment of all kinds

were necessary. This work would keep British

industry hard at work during the whole of the war.

Some factories concentrated on military vehicles,

such as Old Park Works in Wednesbury, where

Valentine tanks were built. The factory also

produced 435 Churchill tanks, 75 Cromwell tanks, and

tank hulls for other manufacturers. Rubery Owen made

aircraft wings and frames, steel helmets, lifeboats,

and carried out all kinds of machining, Wellman

Smith and Owen manufactured shell forging machines,

bridge laying equipment, cranes, and shot furnaces.

Atlas Works, owned by GKN was

asked to double the output of cold-forged nuts and

bolts, and the factory was greatly extended. Half

the cost (£29,000) came from the government. By the

end of the war Atlas Works covered an area of over

20 acres and employed about 3,000 people.

Garringtons, also owned by GKN

produced shells. In July 1940 a shell forging plant

was built at the works by the Admiralty at a cost of

around £100,000. £261,433 was also spent on hammers,

presses and other plant by the Government.

F. H. Lloyds who had the

largest foundry in Europe, made all kinds of

castings, especially for tanks. Large numbers of

women worked in the factories to replace the men who

had gone to war. They carried out all kinds of work,

and were essential to keep the factories operating.

Some women joined the Women's

Voluntary Service (WVS), and carried out an

essential job, doing whatever was needed from

providing tea and refreshments for fire fighters,

collecting scrap metal for the war effort, and

knitting socks, balaclavas etc. for service men.

The first part of the war

These were worrying times, due

to the continuing bad news from Europe. In April

1940 Germany invaded Denmark, followed by Belgium,

Holland, and Luxembourg in May, and Norway in June.

On the 12th May the German army entered France, and

on the 27th May, the evacuation of 340,000 British

and French soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk

began.

On the 10th May Winston

Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as prime

minister, and on the 10th June, Italy declared war

on Britain and France. Eleven days later Italy

invaded southern France, and on the 22nd June France

surrendered to Germany. |

|

Gas Masks

The British Government believed

that some form of poison gas attack would be

inevitable and so gas masks were issued to everyone

living in Britain. By 1940 about 38 million had been

issued.

Adults’ masks were black, and

children’s masks were in bright colours of red,

blue, or green, with bright eye-rims. They became

known as “Mickey Mouse” masks, to make them less

frightening and more appealing.

Each mask came in a strong

cardboard box with a long string handle, which would

be used to carry it over your shoulder. People were

expected to carry them everywhere, but in practice

few did.

Air raid wardens would carry

out inspections and anyone who lost their mask would

be required to pay for a replacement.

They were also available for

young babies in the form of a respirator, which

totally enclosed the child. They came complete with

an air filter and hand-operated air pump. |

|

|

Fire watching

In September 1940 a law was

passed which required factories and businesses to

appoint employees to undertake fire watching. They

had to keep a look out for incendiary bombs which

were dropped in vast quantities at night. They were

quite small, and ignited on impact to start a fire.

Fire watchers were a common

sight in Darlaston, often seen on flat roofs which

were a good vantage point. Many people were involved

in the activity. Some local factories also had a

number of employees who were trained in fire

fighting, and would be on hand in case of an

emergency. |

Fire watching at the Woden

factory run by The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton

Limited was organised by the Local Defence

Volunteers, the precursor to the Home Guard.

Notices like the one above were issued to

members of staff to inform them when they were

required for fire watching duties.

Fire watching at the Woden

factory run by The Steel Nut & Joseph Hampton

Limited was organised by the Local Defence

Volunteers, the precursor to the Home Guard.

Notices like the one above were issued to

members of staff to inform them when they were

required for fire watching duties. |

|

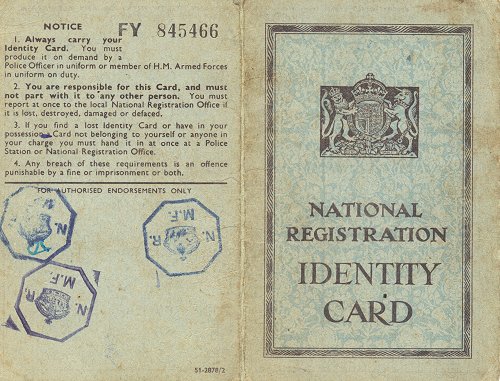

An adult's identity card.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

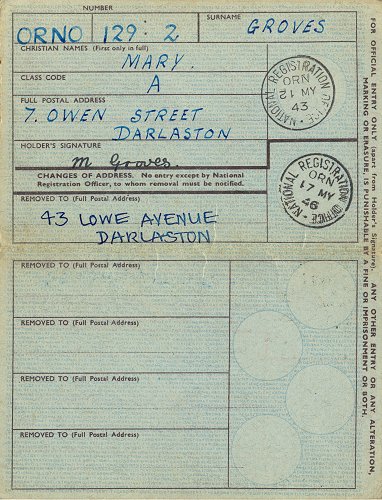

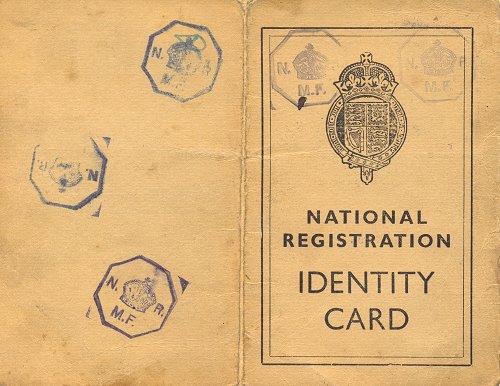

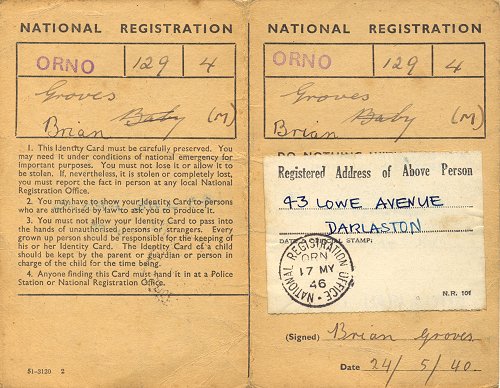

Identity cards were introduced

under the terms of the National Registration Act of

1939.

Everyone, including children,

had to carry an identity card at all times to show

who they were, and where they lived.

Initially they were buff

coloured, but after 1943 Adults' cards were coloured

blue. |

|

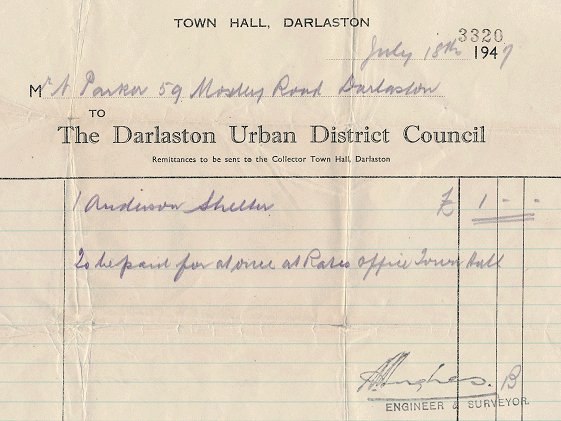

Anderson Shelters

The Prime Minister, Neville

Chamberlain placed Sir John Anderson in charge of

Air Raid Precautions in November 1938. He asked

William Patterson to design a small air raid shelter

that could easily, quickly, and cheaply be erected

in people’s gardens. This became known as the

Anderson Shelter.

It consisted of 6 curved sheets

of corrugated, galvanised steel, bolted at the top,

with corrugated sheets at the back, and an entrance

at the front. The shelter was half-buried, then

covered in earth, and measured approximately 6ft.

6in. by 4ft. 6in. It could accommodate six people.

They were given free to the poor, and could be

purchased by anyone earning over £5 a week.

The shelters were distributed

to towns and cities that were perceived to be under

threat from air raids. Within the first two years,

two and a quarter million Anderson shelters had been

erected. Many families spent long and cold nights in

their shelter after hearing the air raid warning

sirens. The winters of 1940 and 1941 were especially

cold. |

The inside of the identity card.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

|

A child's identity card.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

|

The inside of the card.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

|

Anderson air raid shelters in a

back garden in Ward Street, Walsall. Courtesy of John

and Christine Ashmore. |

Because the air raid shelters

were cold and damp, it could be an unpleasant

experience to spend a night there. Sometimes water

would seep through the earth floor, adding to the

discomfort.

Benches to sit and sleep on would be

built around the inside walls, and candles and

matches were a necessity for lighting.

Due to the

blackout, no light could be showing at night, and so

Hessian sacks were often hung across the open

doorway. Sometimes a family would prefer to stay in

the house during an air raid to avoid the discomfort

of the shelter. They would crawl under the stairs

where possible, or even sit under the kitchen table.

Although few Anderson shelters

have survived, some of the corrugated steel sheets

are still in use as garden fencing.

There were also public air raid

shelters near to public buildings, school air raid

shelters adjacent to schools, and factory air raid

shelters for factory workers. |

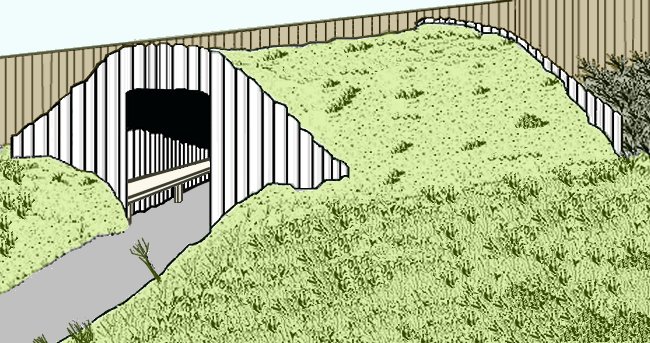

An Anderson shelter in a back garden.

An invoice from the local

council for an Anderson

shelter.

An impression of the air raid shelters

built for Pinfold Street School.

| |

|

Read about how to use

an air raid shelter |

|

| |

|

|

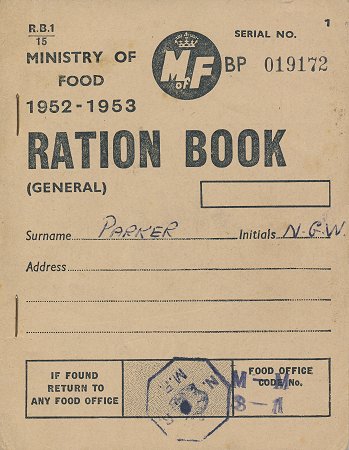

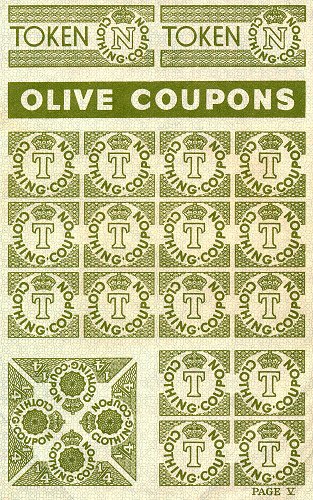

The German U-boats, mines,

aircraft, and surface ships sunk vast numbers of

allied merchant ships, which led to shortages of all

kinds, and the introduction of rationing in 1940.

Everyone was issued with a ration book, which

contained coupons that entitled the owner to buy

food and clothes, and helped to prevent people

hoarding things. The coupons were cut out and signed

by the shopkeeper.

Everyone had to register with

local retailers, whose details were stamped in the

book. Items could only be purchased from their

shops. Rationed items included meat, eggs, fats,

cheese, bacon, sugar, and clothes. Each person was

allowed a new set of clothes each year. Food

retailers had to register with the Ministry of Food,

and were provided with a list of what they could

sell.

Although rationing was strictly

adhered to, the more wealthy members of society

could supplement their food allowance by eating out.

Restaurants were exempt from rationing, which caused

resentment amongst the working classes. To minimise

this, new rules were put into place. A meal could

cost no more than 5 shillings, and consist of no

more than 3 courses. Meat and fish could not be

served at the same sitting.

|

|

Due to the German blockade,

citrus fruits and bananas were not available. Coffee

was also scarce and so alternatives were made from

roasted barley seeds and acorns. People often kept

chickens in their garden as a source of meat and

eggs, and also rabbits. Because milk was in short

supply, most people relied on powdered milk.

Powdered eggs were also popular.

The “Dig for Victory” campaign

started early in the war, and helped people to cope

with the shortages by growing their own fruit and

vegetables. Some schools also took part by

encouraging the children to cultivate a small piece

of land near the school.

The shortages in the shops

continued for many years after the war had ended.

Rationing remained until 1954. |

|

|

|

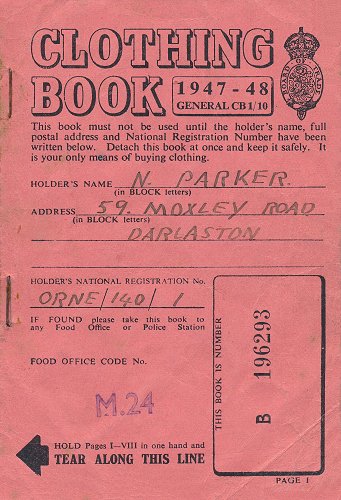

|

A clothes

rationing book and one of the 4 pages of coupons. |

|

Germany’s ruthless expansion

programme continued in 1941 with the invasion of

Yugoslavia and Greece in April, and the invasion of

Russia in June. In December of that year the United

States formally declared war on Germany, Italy, and

Japan. In September 1940 the three countries had

signed the Tripartite Pact, agreeing to support one

another in the war.

The bombing campaign

By the summer of 1940 Hitler

had decided to invade Britain. In July of that year

the German air force, the Luftwaffe, began making

daily bombing raids on British factories, ships and

military establishments, particularly airfields. On

the 7th September the London blitz began, when the

Luftwaffe destroyed many houses, killing 430 people

and badly injuring 1,600 people on the first day.

Hitler believed that he could lower people’s moral

by bombing civilian houses, and force the country to

surrender.

Due to the large number of

factories in Darlaston, the town could have been a

prime target, but German intelligence on British

industry was poor. Birmingham suffered badly due to

its many factories and large population. Around

2,000 tons of bombs were dropped on the city,

killing 2,241 people and seriously injuring over

3,000 people. Coventry also suffered, but to a

slightly lesser extent. The government tried to

confuse the German bombers by enforcing a

'blackout', during which street lights were turned

off, car headlights were covered, and people had to

use blackout curtains to prevent house lights being

seen. It became dangerous to go out at night,

particularly on dark nights. Place names were

removed from buildings to confuse any enemy

paratroopers, and road signs were often turned round

to further increase the confusion.

Luckily Darlaston got off very

lightly, only 3 bombs were dropped on the town. The

first bomb fell on the 5th June, 1941 when a German

bomber attempted to drop a bomb on the Rubery Owen

factory. The large bomb fell short of its target and

badly damaged 5 houses in Lowe Avenue, killing 11

people in the process. Several other houses were

damaged to a lesser extent. |

| The aftermath of the

bombing in Lowe Avenue.

Courtesy of Brian Groves.

|

|

|

My mother recalled seeing it

pass over Moxley Road, where my family lived,

glowing red at the front, and making a whistling

sound as it travelled through the air. After a short

time it went quiet, then there was a loud explosion,

so the bomb had obviously detonated.

My grandmother lived in Berry

Avenue, and as the explosion appeared to come from

that direction, my mother hurriedly went there to

see if everyone was OK. On discovering that the bomb

had passed over Berry Avenue she thought of her

brother and sister-in-law who lived in Lowe Avenue,

so she continued her journey and saw the

devastation.

The houses destroyed were

numbers 34 to 42. No air raid warning had been

given, and so the occupants were in their houses

rather than in the air raid shelters.

Although it was a terrible and

sad event, it could have been much worse. Had it

landed on its target, hundreds could have been killed

or injured. |

The casualties were as follows: |

| Number 34 Lowe Avenue - Henry John

Mumford, age 44, married to Emily. |

| Number 34 Lowe Avenue - Emily Mumford,

age 44. |

| Number 36 Lowe Avenue - Ellen Mills, age

60. |

| Number 38 Lowe Avenue - John Woodward,

age 26, married to Mary. |

|

Number 38 Lowe Avenue -

Mary Woodward, age 25. |

| Number 40 Lowe Avenue - Ethel Cross, age

41. |

| Number 40 Lowe Avenue - Elsie May

Prestidge, age 23, mother of Malcolm. |

| Number 40 Lowe Avenue - Malcolm Thomas

Prestidge, age 4 months. |

| Number 42 Lowe Avenue - Richard Perrins,

age 47, father of Henry and Frank. |

| Number 42 Lowe Avenue - Henry Perrins,

age 15. |

| Number 42 Lowe Avenue - Frank Perrins,

age 12. |

Within a few weeks almost all traces of the bombing

had gone. The council quickly stepped-in and

repaired the houses. |

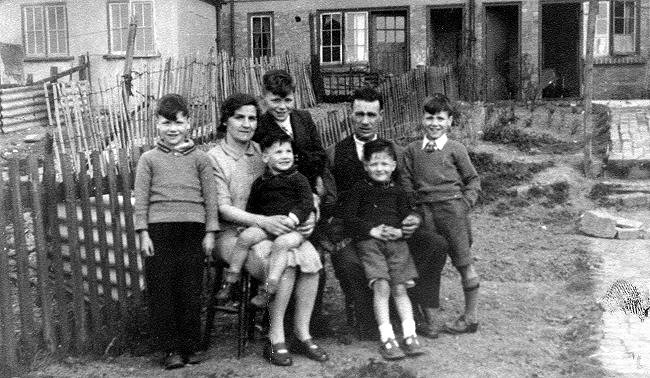

The Groves family

who lived at number 43 Lowe Avenue, from

the mid 1940s. This view of the family

is taken in the garden behind the house.

Left to right: John, Mary with Peter on

her lap, Tom junior, Tom senior, Derek,

and Brian. Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

| Another bomb fell on All Saints' Church in

Walsall Road on the 31st July, 1942. The church was

completely destroyed, leaving a crater 50 feet deep

and 40 feet across. Luckily no one was hurt.

The bomb’s intended target was the nearby Atlas

Works where around 2,000 people were on the night

shift. My father worked at the Steel Nut and Joseph

Hampton Limited, in All Saint’s Road, known as ‘The

Woden’. He remembered being shocked at the

unexpected sight of the crater and the destruction. |

All Saints' Church, Walsall

Road. |

|

The interior of the

church. |

|

Another view of the interior of the

church. From an old postcard. |

|

What was left after the

explosion. |

|

On the 4th August, 1942 the

church council formed a restoration committee and

made plans for the rebuilding of the church.

Services continued to be held in the All Saints' Day

School, which partially survived the blast. Over the next few years

they raised £10,000 towards the new church and also

received £28,320 from the War Damage Commission.

On the same night as the

bombing of the church, another bomb fell by the

Railway Tavern at James Bridge, hitting the cinder

wall in front of the pub. Luckily it did not

explode, it just sank into the soft earth. The bomb had been aimed at

one of the factories in the area, possibly F. H.

Lloyd & Company, E. C. and J. Keay Limited, or the

Darlaston Nut and Bolt Company’s factory in Cemetery

Road, known locally as ‘Bogie Wilkes’. Had the

500lb. bomb exploded it would have not only

destroyed the pub, but also the railway station, the

nearby cottages, and much of Wilkes' factory. When a

bomb disposal team arrived the next day, they

discovered that the bomb was buried several feet

under the ground, due to the soft earth. This

complicated the whole process, and it took many

hours to safely defuse and remove it.

By the time the German bombing

campaign had ended, over 43,000 civilians had been

killed, and over 1,000,000 houses were destroyed or

damaged.

Darlaston people greatly

enjoyed the fun fairs that were held on the Wake

Field by Pat Collins. There was always something new

to look forward to, because Pat was a great

innovator. It is easy to imagine that the enforced

wartime blackout would have prevented such fairs

taking place. It may have stopped others, but not

Pat Collins', he found a way to overcome the

restrictions. In April 1940 he introduced his

blackout fair at Darlaston and Walsall. It was a

completely covered fair, with all of the usual

attractions undercover. It must have been a great source

of enjoyment, especially at a time of so many

restrictions, rationing, and shortages.

From the Walsall Observer, 30th April, 1940.

The mid-war years

The British Restaurant

British restaurants were run by

local authorities, and local committees to provide

cheap meals for the community. They were essential

in areas that had been badly hit by the bombing, and

essential for people who had run out of rationing

coupons. Workers who had no canteen also used them.

The restaurants were set up by the Ministry of Food,

and run on a non-profit making basis. The maximum

price for a meal was 9 pence. By the end of 1944

there were 1,931 of them in the UK, some of which

had been set up in schools and church halls.

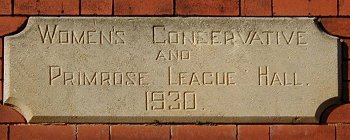

In Darlaston, the Women's

Conservative and Primrose League Hall in Bilston

Street, built in 1930, was converted into a British

Restaurant. It acquired the nickname of "The

Trough", and after the war became the Civic

Restaurant, which remained open for many years. The

restaurant was extremely popular and attracted

customers from many surrounding towns. The building

still survives today on the corner of Bilston Street

and Cramp Hill, and is used by the Darlaston Sons

and Daughters of Rest. |

|

The British Restaurant

building in Bilston Street, as it was in 2006. |

|

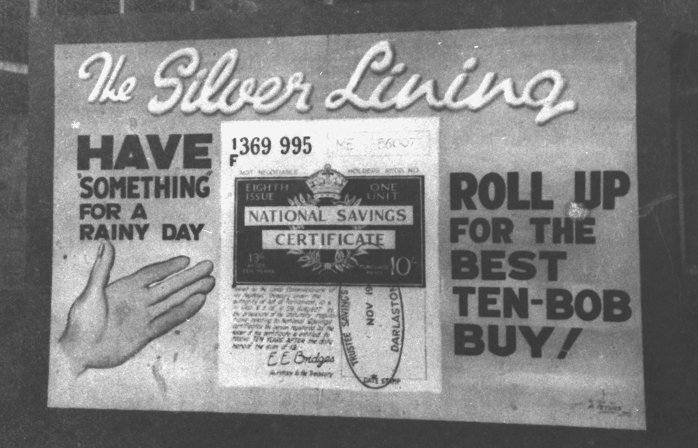

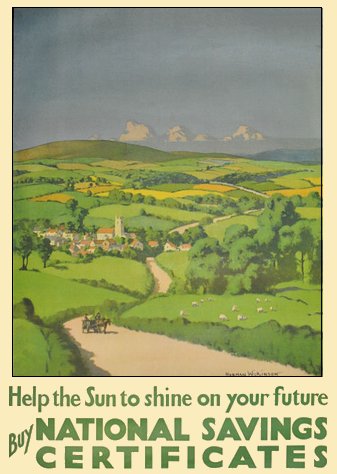

Fund raising and collecting for the war effort

The War Savings Campaign was

initiated by the War Office in 1939 to support the

war effort. Several saving schemes were introduced,

the first being the National Savings Scheme where

you purchased savings stamps and stuck them onto a

card.

The scheme became a great

success, large numbers of people purchased the

stamps, at banks, post offices, and savings kiosks.

Other options were war bonds, savings bonds, and

defence bonds, advertised with the slogan “Lend to

defend the right to be free.”

People were also asked to

contribute to various money raising schemes such as

Warship Week, Wings for Victory Week, Spitfire Week,

all raising much needed cash for armaments. |

|

|

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

Although we tend to think of

recycling as something new, it became an important

way of dealing with the many shortages. People

collected silver wrapping paper, empty toothpaste

tubes, and even unwound wool from old jumpers and

socks. Housewives were urged to hand over their

aluminium pots and pans to become the raw material

for aircraft production. Wrought iron gates and

fences were removed and taken to factories to be

melted down. Paper was in short supply, and so

newspapers were only a few pages long. People kept

the paper which was either burnt on the fire, or

recycled.

Because coal was in short supply, salt

water would be sprinkled on it to make it burn more

slowly, and fallen tree branches could be collected

to supplement the often meagre supply.

Preserves

such as jam were an important way of preserving

fruit when it was plentiful. Similarly eggs were

preserved by storing them in a solution of

isinglass. The shortage of petrol led to the

government asking all drivers to observe a 40mph.

speed limit to help conserve fuel. |

The programme for a concert in

April 1943 that was held at the Regal Cinema to

raise money for the Air Training Corps Welfare Fund.

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

The programme details.

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore.

|

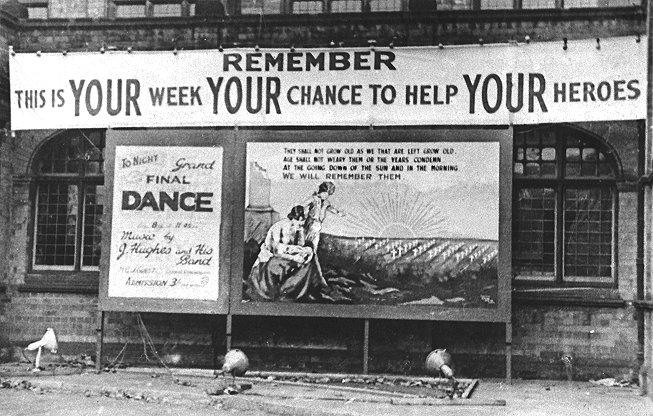

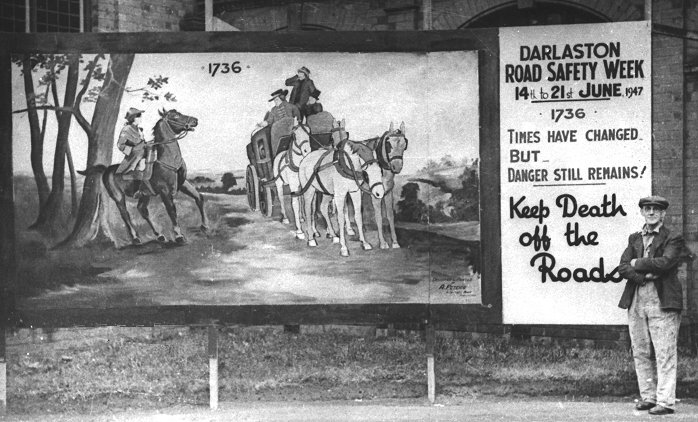

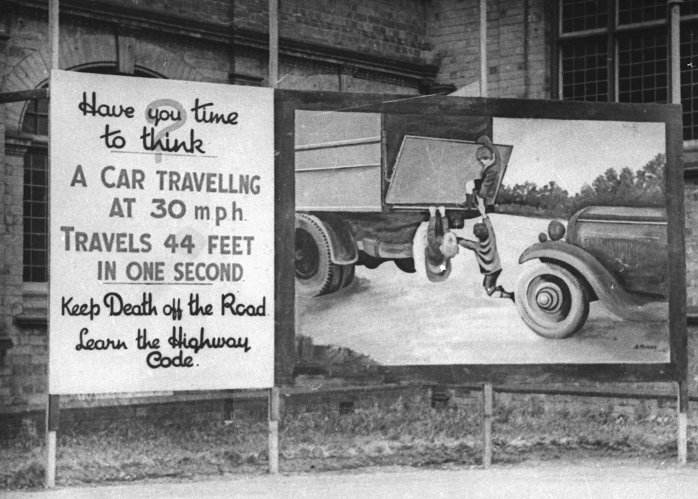

| Albert Peters -

Darlaston's Artist Sign Writer |

| A once well known and well respected figure in

the town was Albert Peters, who turned sign writing

into a form of high art. His signs could be found

throughout Darlaston and the surrounding towns. They

varied from simple name signs, through to pub signs,

and the large signs that he produced for the local

authority, which became landmarks in their own

right. They were works of public art, that were

greatly appreciated by the local population.

I have included photos of some of his better

known signs below. They came from the collection of

the late Howard Madeley. |

Albert Peters. |

|

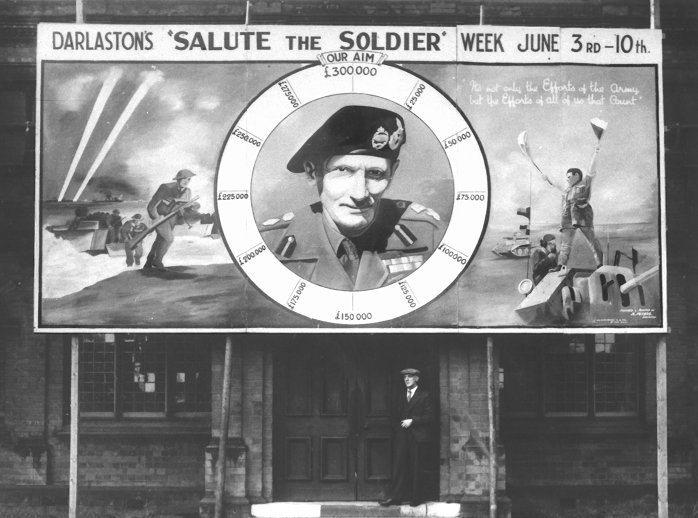

Albert Peters standing below

his poster to advertise Darlaston's part in 'Salute

the Soldier' week, a national scheme to raise money

to equip the army for the final push into Germany.

It took place in 1944, and encouraged people to

provide much needed funds for the war effort. Cash

could be deposited in banks or post offices.

|

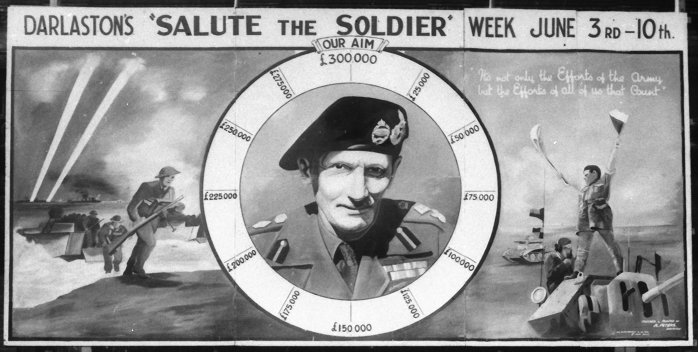

|

A larger view of the poster. |

The poster was placed outside

the Town Hall. The photograph shows the opening

event on Saturday 3rd June, 1944. |

|

Another of Albert Peters' wartime

posters, also hanging outside the Town Hall. |

|

Albert's poster for the

National Savings Scheme. |

|

Another wartime poster.

This one, from 1941, features Albert Peters' brilliant characterisation of the well-known scrap collector

Billy Muggins. |

|

Albert Peters standing beside

one of his many masterpieces. |

|

Another of his road safety

posters. |

A view of Campbell Place, as

seen from Blakemore Lane. Albert Peters and his

family lived in the shop in the centre of the photo.

From the collection of the late Howard Madeley. |

|

An advert from 1972. |

|

Royal visits

The Royal family played their

part in boosting people’s morale by visiting many of

the military, and industrial establishments that

were essential during the war. On the 26th February,

1941 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited GKN’s Atlas Works in Station Street, and on the 14th

January, 1943 the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester

visited the Rubery Owen factory.

The final part of the war

During the last few years of

the war it finally looked as though things were

going our way, although we still faced an intense

struggle with the German forces. Good news arrived

in November 1942 when the British and American

troops won the North Africa campaign. In September

1943 Italy surrendered, and in October declared war

on Germany. In June 1944 British and American troops

landed on the Normandy beaches (known as the D-Day

landings) at the beginning of the campaign to free

France from the Germans. In August the allied troops

landed in Southern France near Nice, and on the 20th

of the month reached Paris. On the 11th September,

American troops entered Germany.

The years of hard work and

shortages now seemed worthwhile, the threat of

German invasion was over, and people started to look

forward to the return to normality. With this in

mind, the government passed new legislation which

was designed to improve the education of young

people, and prepare them for their working life, and

career after school. This was the 1944 Education Act

which introduced the Eleven Plus examination. For

the first time, pupils were allocated a suitable

secondary schools, best suited for their abilities

and aptitudes. Three types of secondary school were

available, grammar schools, secondary technical

schools, and secondary modern schools. The Act also

allowed for the creation of comprehensive schools,

and created a system of direct grant schools, under

which a number of independent schools received a

grant from the Ministry of Education for accepting a

number of none fee paying pupils.

Also in 1944 it was made

compulsory for local authorities to provide school

dinners, which were free for children from low

income families. Good news

continued to arrive from Europe during the early

months of 1945. In April Russia launched its final

offensive on Berlin, and Adolph Hitler committed

suicide. |

|

In May, Germany

surrendered, and on VE Day (Victory in Europe Day)

everyone celebrated the end of the war. There were

street parties, and bonfires, and families looked

forward to the return of their loved ones who were

still on the continent.

Working life soon returned to

normal because of the huge demand for steel goods,

and nuts and bolts. Rubery Owen also benefited from

the shortage of housing by producing large numbers

of pre-fabricated houses. Many of the women who

worked in the factories during the war were replaced

by men returning from the forces. People’s

expectations for the future were high, but the

shortages in the shops continued for many years, the

final rationing books being issued in 1954.

Fighting finally came to an end on the 14th

August when Japan surrendered to the allies. This

was universally celebrated as V-J Day (Victory in

Japan Day). The war had lasted almost 6 years, we

were in a poor financial state, and much of the

country’s infrastructure was in tatters. It would

take many years and a lot of hard work to recover. |

The VE Day street party that was

held in Lowe Avenue. Courtesy of Mavis Young.

|

Some of

the people in the photograph above |

| 1. |

Louise Bumford |

|

32. |

Betty Hall |

| 2. |

Mrs. Harris |

|

41. |

June Bumford |

| 3. |

Margaret Holdcroft |

|

42. |

Janet Bumford |

| 4. |

John E. Lawton |

|

43. |

Edna Hartshorne |

| 5. |

May Lawton |

|

48. |

Mavis Bumford |

| 6. |

Mrs. Clifford |

|

50. |

Margaret Rose Harris |

| 7. |

Mrs. Boffee |

|

51. |

Jeanette Clifford |

| 8. |

Mrs. Evans |

|

52. |

June Clifford |

| 9. |

Jack Hartshorne snr. |

|

55. |

Les Bumford |

| 10. |

Mrs. Stokes |

|

58. |

Ron Bumford |

| 13. |

Mr. Clifford |

|

59. |

Jack Hartshorne jnr. |

| 14. |

Mrs. Richards |

|

60. |

Leslie Bumford |

| 15. |

Bill Holdcroft |

|

61. |

Dennis Evans |

| 16. |

Ethel Stokes |

|

62. |

Daniel Richards |

| 25. |

Gillian Lawton |

|

68. |

Ria Rudge |

| 26. |

John Lawton |

|

70. |

Jack Rigby |

| The dog, a mongrel terrier, belonged to the

Hartshorne family and was called Mick. If you can

recognise anyone else, please

send me an email.

Thanks must go to Jack Hartshorne, Anthony Holdcroft,

Mavis Young, Florence Wilkes and Annis Spinks for supplying the names

of the people above. |

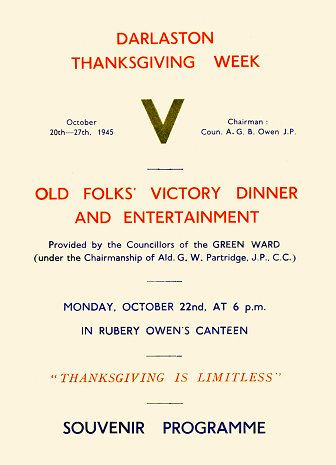

A programme for one of the many

celebrations that were held to mark the end of the war.

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

Black country industries played

a vital role in the war effort. Thousands of firm

diverted much of their capacity to the production of

armaments, which often accounted for 90% of their

output.

One typical firm, the Wellman Smith & Owen

organisation, built specialised machinery for shell

forging, which was used in Canada, Australia, and

America. The machines produced in excess of three

hundred and fifty 3.7 inch aircraft shell forgings

an hour.

By the end of the war some 80 million

shells had been produced on the machines, using

2.125 million tons of steel.

Throughout the war years a

feeling of comradeship prevailed in Darlaston, even

though there were many shortages and hardships.

The large number of factories

could have been a frequent target for the German air

force, but luckily very few bombs fell on the town.

A total of 11 houses were badly damaged, and 401

were slightly damaged.

|

The inside of the souvenir programme

above. Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore.

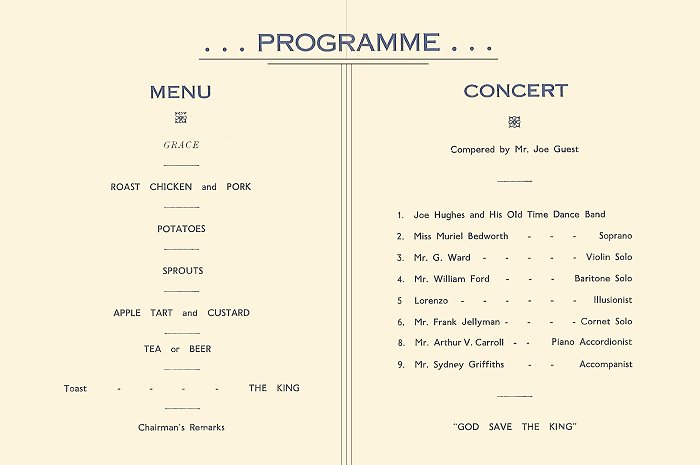

| Out of the many hundreds of

people from Darlaston who fought in the war, 93 were

killed. The plaque on Darlaston’s war memorial lists

12 civilians killed in the war. 11 of them were the

victims of the bombing in Lowe Avenue. Unfortunately

I have no information on the 12th casualty, Annie

Mitchell, who could have died from her injuries,

sometime after the bombing. |

|

|

|

The plaque on Darlaston war memorial

dedicated those who lost their lives due to enemy action

in the Second World War. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Read about a

forgotten

war hero |

|

|

Read about Darlaston

war memorial |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

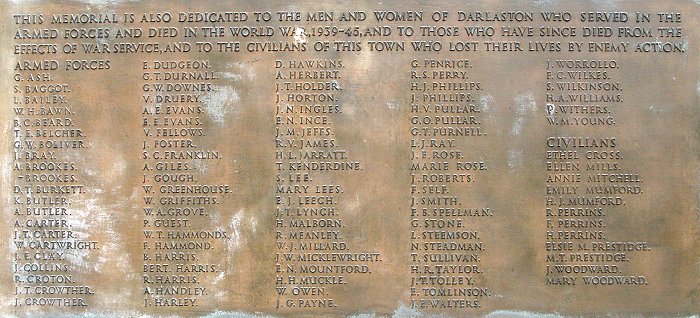

After the war had ended, Darlaston Council held

an exhibition in the Town Hall to inform people of

its many roles and activities.

Courtesy of Christine and

John Ashmore. |

|

The early post war years

The 1950s and 1960s saw

Darlaston at its most prosperous. It grew to be the

leading centre in the country for the manufacture of

nuts & bolts, and its many products were exported

all over the world. Darlaston's complete domination

of this industry covered all types of nuts & bolts,

screws and rivets. Thousands were employed in the

industry and a very high degree of skill and

craftsmanship was shown by them.

The many other engineering

concerns in the town also prospered, producing a

diverse range of products including forgings,

cycles, machinery, castings, holloware, motor

components, and structural steelwork. Other products

included soap, candles, rope and twine.

A full and flourishing

industrial and economic life appeared to be assured

for the people of Darlaston, with many varied and

interesting opportunities for the younger

generation. |

Darlaston war memorial. |

| In 1952 the new All Saints Church in Walsall

Road opened as a replacement for its predecessor,

which was destroyed by the German bomb in 1942. The

new church, designed by Lavender & Twentyman of

Wolverhampton was built by E. Fletcher of

Kingswinford at a cost of £38,320. |

|

The

western end of Foundry Street in

the mid 1950s. All traces of the

street have now disappeared.

It

ran from Catherine's Cross to

Wiley Avenue, in parallel with

Park Street.

The houses are

identical to much of the town's

cheaper mid Victorian dwellings,

which were demolished in the

1950s and 60s. |

|

Marion Turner, whose husband Malcolm

grew-up in the late 1930s and 1940s at number 35 Foundry

Street has kindly sent a list of the residents of the

properties in the above photograph, during those years.

They are as follows, from left to right:

| Number

34 |

George and Sarah Turner, grandparents of

Malcolm in number 35. |

| Number

35 |

George and Kate Turner, and their

children Malcolm and Kenneth. |

| Number

36 |

Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd and their children,

Jeffrey, Janet and Ann. |

| Number

37 |

The Palmers, brother and sister. |

|

Coal Yard |

The Simpsons who also owned

the adjacent shop. |

| Past the shop lived the

families of Hawkins, Upton and Thomas. |

Malcolm Turner went to Pinfold Street

School, and his father George worked for many years as a

machine bolt header for Guest, Keen & Nettlefolds. |

|

The council's housing development

schemes continued at a rapid pace. The older substandard

houses completely disappeared by the mid 1960s.

Over 2,000 council houses had been built since the end

of the war, including the Bentley Estate, which had

shops, a library, a Parish Church, and two secondary

modern schools.

|

An advert from 1954. Courtesy of

Christine and John Ashmore. |

The front cover of a 1954 council

tenant's handbook. Courtesy of Christine and John

Ashmore. |

|

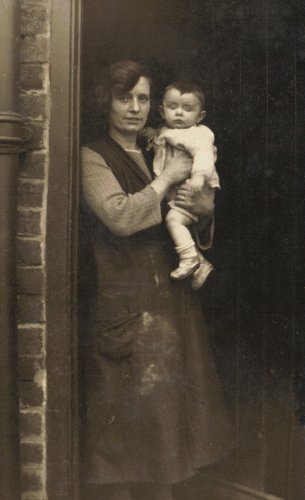

Kate

Turner and her son Malcolm at the back door

of 35 Foundry Street. The photograph

was probably taken in 1936. |

|

|

|

Return to The

Inter-War Years |

Return to

Contents |

Proceed to The

Post-War Years |

|