| |

|

| Read about the disastrous

1918 outbreak of 'Spanish Flu'. |

|

| |

|

|

The

Economy

Immediately after the end of the

First World War, there was a short-lived boom in the

economy, which lasted until late in 1919, but things

rapidly changed. The early 1920s were a time of

recession, a time of hardship for many people. The First

World War greatly stretched the nation’s finances. It

disrupted our trade, and led to the rise of foreign

competition, and the loss of many of our traditional

exports, including steel, coal, and textiles. The

country had previously grown wealthy because of its

pre-eminent trading position in the world, the loss of

which, led to the decline of many of our once great

industries, and substantial job losses. In 1922 there

were 9,457 people out of work in Walsall alone.

The war had been funded by selling

foreign assets, and borrowing large sums of money, which

led to a large national debt. Britain’s interest

payments amounted to around forty percent of the

national budget. In 1920 the rate of inflation was twice

as high as in 1914, and the value of the pound fell. |

The Bridge in the early 1920s. From an old

postcard.

The Bridge in the early 1920s. From an old

postcard.

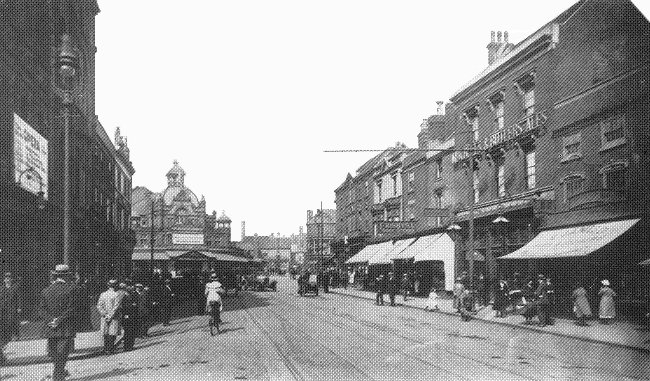

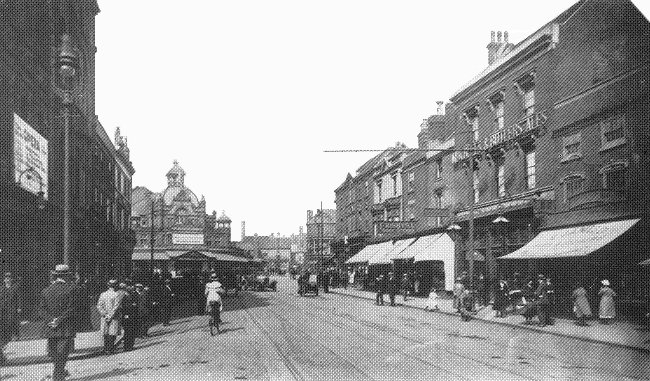

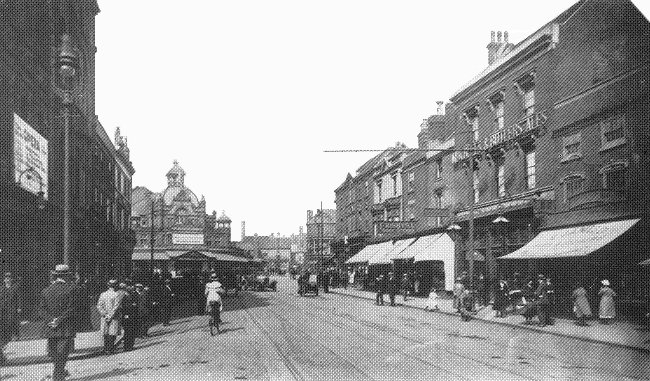

Park Street in around 1925. From an old

postcard.

Park Street in around 1925. From an old

postcard.

|

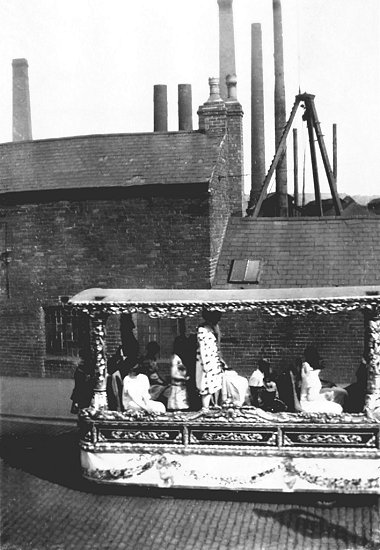

A carnival float in Pleck Road in

the 1920s. Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore. |

|

Another carnival float in

Pleck Road in the 1920s. Courtesy of Christine and John

Ashmore. |

|

Homes for All

By 1921 the population of Walsall

had reached 169,406. This led to a desperate housing

shortage, made worse because no houses had been built in

the borough since before the war. Private builders could

not afford to provide the necessary homes, which

immediately after the war were costing between £1,000

and £1,200 to build. Ironically this sum fell to a

little over £300 within ten years.

The housing shortage was a national

problem and so the Government provided subsidies for

local authorities, who were now required to provide

housing under the terms of the 1919 Housing Act. Walsall

Council started its municipal housing scheme in 1920

under the control of the Health Committee, but as

demands grew, a special Housing Committee was appointed.

The first council houses were built

in Blakenall Lane and Haskell Street in 1920, the first

to be completed being numbers 94 and 96 Blakenall Lane,

now opposite Blakenall United Reformed Church. By 1927 a

total of 450 houses had been built on the Blakenall

estate.

By 1935 there were over 5,400

council houses in the town, each with a bathroom and a

garden. There were non-parlour types with three

bedrooms, and a few with four. There were parlour types

with three bedrooms, a sitting room, and a living room.

The houses were distributed as follows:

| Blakenall and

Harden – 1,100 |

| Palfrey – 1,000 |

| Field Road – 963 |

| Wolverhampton

Road, Pleck and Bentley – 850 |

| Bloxwich and

Leamore – 700 |

| Fullbrook and

Delves – 400 |

| North Walsall –

350 |

| Chuckery and the

central area – 100 |

| Homes for old

people – 78 |

|

|

In 1935 the charge on the general

rates for council houses was £23,675, with a capital

cost of £2,093,209, and weekly rents amounting to

£2,500. In March of that year the 5,000th council house

was completed at 11 Walstead Road West, and by the end

of the 1930s 7,963 council houses had been built.

Some of the houses were built as a

result of the 1930 Housing Act which encouraged mass

slum clearance, and the removal of poor quality housing.

Houses were demolished in James Street and Ann Street in

Ryecroft, and in Short Acre Street, and Long Acre

Street. This was followed by the clearance of slums in

Peal Street, Dudley Street, Lower Rushall Street, and Upper Rushall Street.

In 1937 many of the old

buildings in Digbeth were demolished, and new council

houses were provided for the occupants, in Field Road, Fullbrook, Mill Lane,

and Moat Road.

Unemployment and strikes

By the mid 1920s many industries

were still suffering, particularly after the decision in

1925 keep Britain in the Gold Standard, so that the

pound was equal to 4.85 dollars. This led to high

interest rates, and over-priced exports.

One of the country’s most important

industries, coal mining, had been in decline since the

start of the First World War, and many miners were

laid-off. The heavy use of coal during the war led to

the depletion of many seams, so that when the war ended,

Britain exported less coal, allowing other countries

including the United States, Germany, and Poland, to

fill the gap. In 1924 coal prices fell because of the

Dawes Plan, which had been designed to set targets for

German reparation payments. As part of the payment,

Germany was allowed to export coal to France and Italy,

which led to a further decline in the UK mining

industry. In 1926, mine owners announced their intention

to further reduce miner’s pay, and lengthen their

working day. Negotiations between the TUC and the mine

owners, failed to reach an agreement,

and so the TUC called a general strike to support the

miners, which was to begin on 3rd May. |

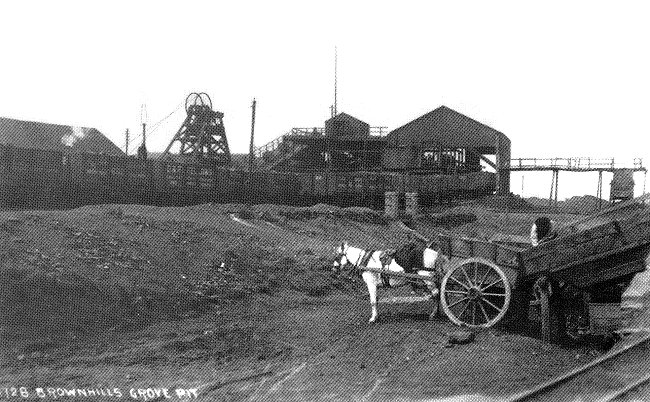

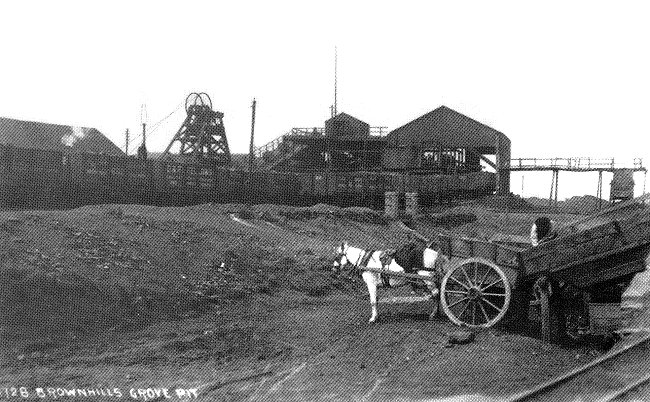

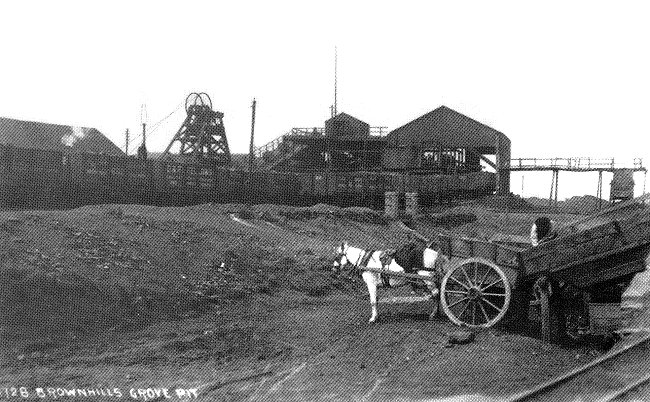

One of Walsall's deep coal mines, Grove

Pit at Brownhills. From an old postcard.

One of Walsall's deep coal mines, Grove

Pit at Brownhills. From an old postcard.

|

Large numbers of people from all

industries joined the strike, which quickly paralysed

much of the country. In Walsall there was no public

transport because trains, trams, and buses were out of action.

Hundreds of strikers filled the town centre, and strike

bulletins were posted outside the Labour Club in

Bradford Street. An emergency committee was formed to

oversee the distribution of essential supplies, and

around 1,000 people signed-up as volunteers to help.

Three hundred and fifty special constables were sworn-in

to be ready in case of lawlessness, but it all went-off

peacefully, with little violence. The strike ended on

12th May, although the miners battled-on until November,

when their strike collapsed.

The strike led to lack of orders,

and a depression in many local industries. Around 2,300

workers were laid-off, including 500 in the leather

trades. Some less fortunate strikers were not given their

jobs back on their return to work,

particularly in public transport. People laid-off were

entitled to benefit from the Poor Law Guardians, and

further help was provided by a distress fund.

The families of striking miners

suffered greatly. By June, around 2,600 miner’s children

were being fed at soup kitchens throughout the town.

They were located at:

The Turf Tavern, Bloxwich; Field

Street School, Bloxwich; the Blue Pig Inn, Bloxwich;

Blakenall Church School; the Nag’s Head, Little

Bloxwich; the White Horse Inn, Green Lane; and John

Street School.

Committees were set up in Aldridge

and Pelsall to help, and hundreds of people scoured

Bentley Common, and the old spoil heaps around Pleck to find coal for heating. Although many

of Walsall’s industries had suffered as a result of the

strike, and unemployment was high, things slowly

improved, albeit briefly.

The top of Park Street in the

1930s. From an old postcard.

By the late 1920s, the United

Kingdom had still not recovered from the effects of the

First World War. Production was still below previous

levels, and many people were out of work. Everything

suddenly got worse after 1929 as a result of the stock

market crash in New York which affected much of the

world. The demand for British products fell, so much so

that by the end of 1930 unemployment more than doubled,

from one million to two and a half million, and exports

halved.

Park Street under water in June

1931.

The unemployed had to seek

financial help from the Public Assistance Committee

which means-tested applicants before allowing them to

receive benefit. In order to help families in distress,

Walsall Council introduced a scheme to provide

two-course midday meals for needy schoolchildren. By

February 1934, free meals were being provided for 500

children, six days a week. Things didn’t really improve

until the years immediately before the Second World War,

when industry began to ramp-up, thanks to the orders

that were received

for essential war work.

Lichfield Street and the Town

Hall. From an old postcard, courtesy of Christine and

John Ashmore.

Walsall market and High Street.

From an old postcard.

Council Projects

Walsall Council attempted to help

the many people who were out of work by instigating

public works schemes for the unemployed. The schemes

included the building of the open air swimming pool at

Bloxwich, the levelling of Blakenall playing fields, and

improvements to the Arboretum, including the upgrading of

the open-air baths, an extension to the children’s

playground, a putting green, new footpaths, and more

tennis courts. The Rock Gardens were added in 1924 along

with tubular swings, and a merry-go-round. |

|

The bandstand in the arboretum

in the late 1920s. From

an old postcard. |

|

A number of road improvements were

also carried out to help the unemployed. The most

important was the building of the new road from Foden

Road to Bescot Road, which was originally called the

Ring Road. In 1931 when the borough was extended, with

the addition of an area to the north and west, including

part of Bentley, the road name was changed to Broadway.

Several roads were widened including Lichfield Road in

Bloxwich, Aldridge Road, Bloxwich Road, Bridge Street,

and Sutton Road.

In 1930 the council decided to

spend £224,000 on public works, including a new

swimming baths, an abattoir and cold storage facilities,

an extension to Ryecroft Cemetery, and improvements to

sewage, drainage, and public parks.

By 1931 the population of Walsall

had grown to 181,114, and 30 percent of the workforce

was unemployed.

A 1934 view of Craddock's Farm at

Pleck looking towards the town centre. From an old

postcard.

| |

|

View some

photographs of a parade

of works' bands from the 1930s |

|

Transport

|

|

From 1935. |

In the 1930s two branches of the

Wyrley and Essington Canal closed, due to the declining

mining industry. The first, the Lord Hay's Branch

(also spelled Lords Hayes Branch), was

abandoned in 1930. It ran from Fishley to the Lords Hayes

coal pits in Essington.

The second, the Daw End branch

ceased to be used in the late 1930s. It ran from Catshill Junction, Walsall Wood, to the Hay Head

limestone quarries. In 1954 both were filled-in .

On the railways, North Walsall

Station built by the Wolverhampton and Walsall Railway

in 1872, and operated by the Midland Railway from 1876,

closed in 1925. It stood just to the west of Bloxwich

Road.

In 1928 motor buses began to

replace the trams, which ceased running in 1933. Trolley

buses were introduced in 1931 on the Willenhall route,

and the central bus station, on the site of the former

Blue Coat School in St. Paul's Street, opened in 1935.

It was built after the Bluecoat School moved to

Springhill Road in 1933.

|

|

The same year saw the opening of

Walsall Municipal Aerodrome on 230 acres of land beside

Aldridge Road, south of Aldridge. It had a short runway

just 900 yards long, much too short for the larger

aircraft of the day. It also had a considerable slope,

being situated on the side of Beacon Hill, the highest

ground in the area. The official opening took place on

6th July, 1935.

In 1938, Helliwells Limited, a firm

specialising in the repair and maintenance of aircraft,

and the manufacture of aircraft components leased a

large factory on the site from the Corporation. They

opened a flying school in 1943, and also manufactured

motorcycle sidecars, motor scooters, and sports cars

using the 'Swallow' name. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Read about

Swallow Motor Scooters |

|

|

Read about

Swallow Sports Cars |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The aerodrome became the

headquarters of the South Staffordshire Aero Club

(previously known as Walsall Aeroplane Club) which had 50

flying members and 100 non-flying members. A club house

with a bar and small office was built on the site, along

with a hangar, large enough to house four or five small

aircraft. The council employed an aerodrome manager, who

also acted as a ground engineer.

A number of events were held at the

aerodrome including a sailplaning display featuring

gliders that were towed into the air by powered

aircraft, or a winch. The event took place on 26th June,

1938 and starred the well-known female aviator, Amy

Johnson, who made two fights, one in a Kirby Kite

glider, and another in a Gull sailplane.

The event attracted about 6,000

paying spectators, many of whom came to see Amy. On her

second flight as she returned to land, she caught a wing

tip on the perimeter fence, which caused the glider to

flip over. Luckily she was unhurt, although somewhat shaken. She quickly returned to the house of her

friend, John V. Rushton (known as Jack) at 134 Mount Road, Penn,

Wolverhampton, where she was staying. Jack Rushton was

the chief instructor at the Midland Gliding Club. |

From an old postcard. |

|

Amy Johnson. |

|

The aerodrome was the scene of

another crash landing a few weeks later. On 14th July an

RAF Harrow twin-engined bomber on a flight from

Driffield to Southampton attempted to land on the

runway, which was far too short for an aircraft of that

size. It overshot the runway and came to rest in a

hedge, just off Longwood Lane. Luckily the pilot, a

local man, Pilot Officer R. N. Haynes was unhurt.

Unfortunately he was killed three months later in an

identical aircraft which came down in the Channel.

The Aero Club survived until the

beginning of the Second World War, and was not revived

afterwards. In the late 1940s Walsall Council considered

enlarging the airfield and extending the runway, but as

Birmingham and Wolverhampton were extending their

airfields, it was felt that such a project could not be

viable.

An advert from 1954.

Walsall Airport and Helliwells

factory.

In the 1950s the airfield was

mainly used by Helliwells for aircraft servicing, the

production of aircraft components, and for the flying school.

The firm had an extensive machine shop and tool room,

detail shops, and a good assembly area. Components

produced for the aircraft industry included bomb doors,

engine cowls, and even complete wings. One of the firm's

largest customers was the R.A.F.

In 1956 the company decided to

transfer their operation to Elmdon because the

airfield at Walsall had become too expensive to run. Work on

the last aircraft to be serviced there, a Harvard, had

been completed in the summer. On 8th October, 1956 Helliwells

cancelled their lease, and the

airfield closed. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

World War 1 |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to

Pat Collins |

|