|

Life in the

Post-Victorian Era

For many working class families,

life was hard in the early part of the twentieth

century, and expectations were low. People worked long

hours for low wages, and lived in poor and overcrowded

housing. Skilled men could earn up to thirty shillings a

week, and unskilled men could expect to earn no more

than twenty shillings a week. Trades unions were

becoming increasingly militant, and strikes happened

frequently. In 1913 a strike of engineering workers

lasted over two months in an attempt to raise the

minimum wage for unskilled workers to twenty three

shillings a week. There were also strikes on the

railways, and in the coal mines, not forgetting the

great unrest at nearby Wednesbury when the tube makers

downed-tools.

Food was expensive, so much so that

some families spent sixty percent of their income on it,

and malnutrition amongst children became commonplace.

Due to the harder and more stressful living conditions,

and the lack of modern medical care, life expectancy was

much shorter than today, being around fifty years for

men, and fifty four years for women.

The turn of the twentieth century

saw the dawn of the welfare state, but only in a modest

way. In 1909 the first old age pensions were paid to

people over the age of 70. They were entitled to five

shillings a week. Two years later the 1911 National

Insurance Act was passed to provide sickness and

unemployment benefit for people. The scheme was

compulsory for all wage earners between the ages of

sixteen and seventy. They had to contribute four pence a

week to the scheme, which was supplemented by an

additional three pence from the employer, and two pence

from the state. In return, workers received free medical

attention and medicine, and were paid 10 shillings a

week for the first 13 weeks, and 5 shillings a week for

the next 13 weeks. Unemployment benefit consisted of

seven shillings a week, beginning after the first week

of unemployment, and lasting for fifteen weeks in any

single year. It was paid at labour exchanges, which

first appeared in 1910.

For many years Britain had been the

dominant economic power in Europe, but by 1914 Britain

was being outperformed by Germany, which had previously

been an important customer for many of our largest

industries. As Germany’s industries flourished, British

exports suffered, and some industries began to decline.

The Outbreak of War

For some years imperialism had

grown in most of the major European countries, which

meant that at some time, the outbreak war was almost

inevitable. It officially began on 28th July, 1914 with

the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of

Austria, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his

wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, who were shot dead

in Sarajevo, by Gavrilo Princip, one of a group of six

Bosnian Serb assassins. After the assassination,

Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to the Kingdom of

Serbia and prepared to invade.

At the time there were two groups

of allies in Europe:

|

The Allied Forces - France, United

Kingdom, and Russia.

The Central Powers - Germany and

Austria-Hungary.

|

Britain had a treaty with Belgium,

and so declared war with Germany when the German army

invaded Belgium and Luxembourg, on its way to France.

Soon all the major European powers were involved in the

war, which within a few years involved many countries

throughout the world.

When Britain declared war on 4th

August, 1914 celebrations were held throughout the

country. Most people believed it would be a quick and

simple affair that would be over by Christmas.

Patriotism was high, and large numbers of men rushed to

join the forces to answer the call to arms. The

government wanted 100,000 volunteers and began a large

recruitment campaign which bombarded the public with

posters. This was so successful that within a month

750,000 people had volunteered.

Sadly it was not to be a quick

affair. As the German troops entered France, the French

and British troops moved northwards to meet them, and

the massive armies dug-in, starting the terrible trench

warfare which would last for four years.

The Home Front

The day before the declaration of

war was a Bank Holiday, and crowds gathered on The

Bridge and in Park Street, awaiting an announcement. |

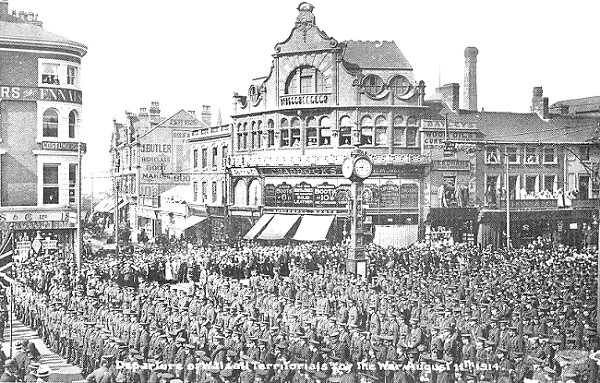

The Walsall volunteers on The Bridge. 11th

August, 1914. From an old postcard.

The Walsall volunteers on The Bridge. 11th

August, 1914. From an old postcard.

|

The Walsall volunteers, members of

the 5th Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment

were recalled from their annual camp and mobilised in

Walsall where they were billeted in local schools. On

the 11th August they paraded on The Bridge for a Civic

farewell. After a speech by the mayor, they left for

Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, and the next day

travelled to Luton for training. They landed at Le Havre

on March 1915. The battalion consisted of men from

Walsall, Bloxwich and the surrounding area. Members of

the regiment served at Mons, Ypres, Loos, The Somme,

Saint Quentin Canal, and Gallipoli.

Over 12,000 men from Walsall joined

the armed forces, but sadly over 2,000 of them never

returned. Because so many men had joined-up, there was a

shortage of labour. Industry was essential to the

winning of the war. Factories worked flat-out producing

vital war work and armaments for the armed forces, but

initially suffered because of the shortage of skilled

men. Their roles were taken-over by women, who for the

first time were allowed to work in some of the more

physically demanding factory jobs which had previously

been considered to be only suitable for men. Women also

kept many of the essential services in operation

including the trams, the railways, and our farms. They

also worked in munitions factories.

|

Another view of the gathering on The

Bridge. From an old postcard. Courtesy of Paul Bowman.

|

In August 1914 Parliament Passed

the Defence of the Realm Act which gave the government a

range of new powers to prevent anyone assisting or

communicating with the enemy. The press was censored, to

keep-up people’s morale, and plans were made to ensure

that scarce resources were correctly used. The Admiralty

and the Army Council were given powers to take-over any

factory or workshop for the production of arms,

ammunition, or products for the war-effort. Within

twelve months the shortage of munitions led to the

government setting-up its own arms factories, and

eventually taking over the vitally important coal

industry. All manufacturers turned their skills towards

the war effort including Shannon’s Mill where overcoats

and uniforms were made for the armed forces, and the

Talbot-Stead Company which supplied boiler tubes to the

Admiralty.

The futility of the stand-off

between the vast armies meant that large numbers of

people were killed or wounded, and enormous numbers of

men were needed at the front. In the autumn of 1915 Lord

Derby headed a campaign which resulted in around 300,000

new recruits, but it was still not enough to meet the

needs of the army. In January 1916 the prime minister,

Herbert Asquith introduced conscription for all single

men aged between eighteen and forty, which was seen as

the only way to get all of the troops that were needed.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Read about the

Zeppelin raids in January 1916 |

|

|

Read

about the airship onslaught which rocked Midland

towns |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The Later War Years

In 1915 the Germans declared an

official naval blockade of Britain, and threatened to

sink any ships sailing into British ports. The Americans

immediately objected because many of their cargo ships

sailed here, and the blockade was cancelled. Two years

later it was reinstated, which caused the Americans to

enter the war.

|

Members of the Red

Cross, at The Bridge, raising funds to buy

more ambulances. From an old postcard. |

In January 1918 Walsall appointed

its first two women police officers, the first in the

Black Country. They were Miss Tearle, and Miss Williams.

After undergoing basic training in London, and gaining

some experience, they started their duties at Walsall in

May 1918. They were paid 35 shillings per week, plus a

wartime bonus of 10 shillings. |

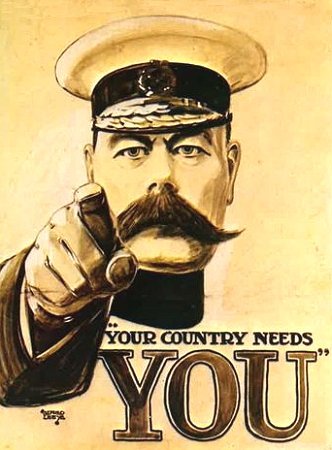

Perhaps the best known and most enduring

image of the First World War is this one of Lord Kitchener. |

|

This propaganda poster urges women to help in

building much-needed aircraft. |

|

|

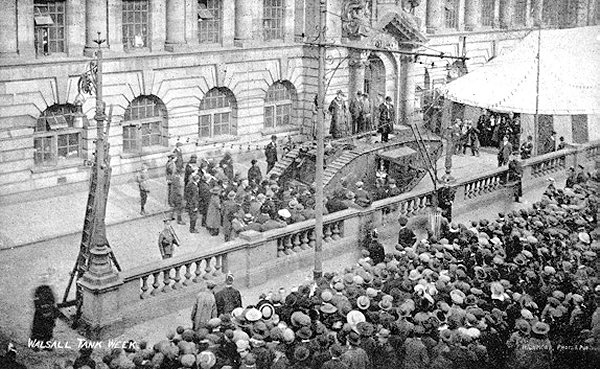

Tank Week in Walsall. From an old

postcard. |

| In March 1918 a British tank which

had been given the name 'Julian' was placed outside the

Town Hall for a week as part of a fund-raising scheme

for the war effort. At the end of Tank Week a total of

£832,207 had been raised. The tank then continued on its

fund-raising tour of the country. |

|

Another view of 'Julian' the tank.

From an old postcard. |

|

From an old postcard. |

|

The blockade by the German U-boats

led to food shortages, rising prices, and long queues at

the shops. Both sugar and wheat were in short supply.

Due to the shortage of wheat, the Ministry of Supply

recommended that 20lb. of potatoes should be added to

every 280lb. sack of flour. The situation worsened and

led to the introduction of food rationing in February

1918. The weekly ration for each person included 15 oz

of meat, 5 oz of bacon, and 4 oz of butter or margarine.

During the war thousands of Belgian

citizens fled to this country, and Walsall quickly came

to their aid. Hostels were set-up for around 150 people

in Lysways Street, Moss Close, and at Aldridge,

Bloxwich, Pelsall, and Rushall. The refugees were

repatriated after the war.

In 1918 after a German offensive

along the western front, the Allies and the American

forces successfully drove them back, leading to the

armistice on 11th November, 1918, and victory for the

Allies.

The news of the victory quickly

spread throughout Walsall. The Walsall Observer received

a telephone call informing the staff that the war had

ended. They hung a yellow banner from a window on the

first floor, on which was written the word PEACE.

Church bells rang, factory hooters

sounded, flags were flown everywhere, and large crowds

gathered in the town centre. Speeches were made on The

Bridge, buildings were illuminated, bands played in

public parks and everyone celebrated the return to

peace.

The peace agreement was formally

signed on 28th June, 1919. Peace celebrations were held

in the town on 19th July, including a Civic procession,

and tree planting ceremonies at Blakenhall and Bloxwich.

On 24th July the council decided to build the war

memorial in Bradford Place, and cast bronze tablets for

the Town Hall, which listed the names of the dead. A

total £9,208 was raised for the purpose. Other events

included the building of the war memorial in Darlaston,

and the building of the Memorial Park in Willenhall to

honour those who had given their lives in the war.

The Cenotaph, Bradford Place. From

an old postcard. |

|

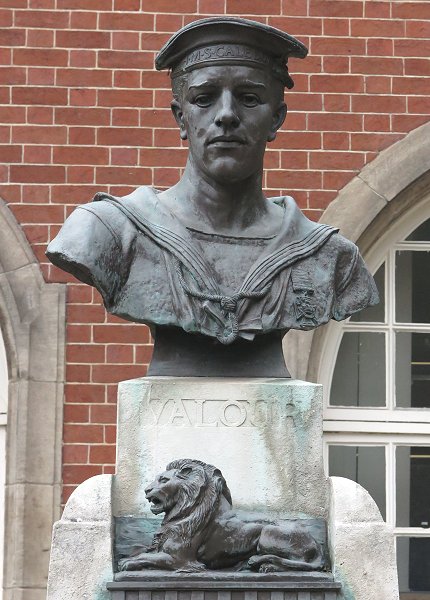

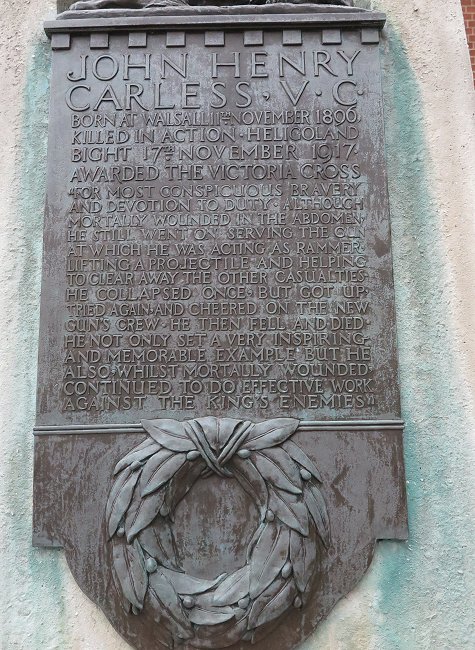

The memorial to John Henry Carless. |

Walsall also erected a memorial to

John Henry Carless who received a Victoria Cross. His

bust stands on a plinth outside the museum in Lichfield

Street. He was born on the 11th November, 1896 in

Caldmore, where he attended St. Mary's Roman

Catholic School. In 1910 he won a gold medal when he

played in the finals of the English Schools Soccer

Shield. He worked as a currier in a local leather

works before joining the armed forces. He initially

volunteered for the army, but was turned down on

medical grounds. He then volunteered for the navy

and was accepted on the 1st September, 1915.

He served as an Ordinary Seaman aboard HMS Caledon, which took part in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight on

the 17th November, 1917. During the

battle he was working as a rammer on one of guns, and

was wounded in the abdomen. Although severely injured, he

remained at his post, and helped to move other

casualties. After collapsing once, he fell again and

died. He was just twenty one years old.

The bronze bust was produced by R. J. Emerson of

Wolverhampton and stands on a base of Portland

Stone. It was unveiled on the 21st February, 1920 by

Rear Admiral Sir Walter H. Cowan, whose flagship, at

the time of John Henry Carless's death had been HMS

Caledon. |

|

In 1923, Oxford Street, Caldmore was renamed

Carless Street and Regent Street became Caledon

Street.

In December 2009

a memorial plaque commemorating John Carless and two

other recipients of the Victoria Cross was unveiled at

the Town Hall. The other two recipients are James

Thompson, and Charles George Bonner. The war greatly helped the cause of

women’s emancipation and gave them a greater degree of

independence than before.

Although many women lost their

jobs when the hostilities ended, and the men returned,

they now had a more prominent status in society and

increased expectations for the future.

The

Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women over 30

years old the right to vote, but they had to be a

member, or married to a member of the Local Government

Register, or a graduate, voting in a University

constituency.

They had to wait another ten years until

the passing of the Representation of the People (Equal

Franchise) Act 1928 to gain the same voting rights as

men. |

A close-up view of the

memorial to John Henry Carless. |

|

| One of the casualties, Bertie

Henry Crick,

Corporal 9362, 7th Battalion, South Staffs

Regiment

The

following information was kindly supplied by

Mark R. Cooper, Bertie's Grandson.

Bertie was born in Wolverhampton on Sunday 13th

April 1890, to John Henry Crick and Bertha Elizabeth

Crick. His father, a baker,

moved to Wolverhampton from

Northampton and Bertie became a moulder in a local

foundry. He lived at

111 Green Lane, Walsall and

married

Edith Sarah Kettledon, a laundress from Wednesbury.

They were married on Friday 26th December, 1913 at

St. Michael’s Church, Caldmore and moved to 66

Orlando Street, Walsall.

At the

outbreak of war,

Bertie enlisted in the

South Staffs Regiment

and was drafted to

Gallipoli on Saturday 11th September, 1915. In

December of that year, when the British troops were

withdrawn from Gallipoli, he served in Egypt.

He returned to France

on

Saturday 24th February, 1917 and

was promoted to

Corporal.

His battalion moved into Belgium and took part in

the terrible trench warfare that characterised the

war. On Sunday 15th July, his battalion moved from Camp

'O' near Poperinghe to the trenches about a mile

north of Ypres, to relieve the 4th and 5th

battalions.

Marching to war. From an old

postcard.

The

trenches were in full view of the

German artillery on nearby

Passchendaele Ridge. The German troops bombarded

them with

shells and rifle fire, which resulted in many

casualties. On 17th July, during his second day in

the trenches, Bertie was seriously wounded, either by an

exploding shell or rifle fire and died. He was just

27 years old.

The

battle continued until 31st July when the allies

captured the German held

Passchendaele Ridge. During the battle over 300,000

British and allied soldiers were killed or

wounded in one of the most horrific battles of the

First World War.

Bertie is buried in La Brique Military

Cemetery No.2 with his colleagues, in grave 1.W.5.

He is commemorated on the Roll of Honour at the Menin Gate

Memorial in Ypres, and in Walsall Town Hall, and

also in St. Matthew’s Church.

His widow Edith, later married Sergeant Joseph Booth Gretton in 1919

and they lived at Clay

Street, Penkridge. He also fought at Ypres,

where he was gassed and discharged, being unfit

for service. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Public Houses |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to

The 1920s |

|