|

Elwell-Parker,

Limited

Thomas Parker and his family moved to

Wolverhampton from Coalbrookdale, in October 1882. Thomas had agreed

to go into partnership with Paul Bedford Elwell, to manufacture

accumulators at Paul’s premises in Commercial Road, from where he

ran the Patent Tip and Horseshoe Company. The Parker family lived in

St. Jude's Road and their daughter Jessie Eliza was born there in

March 1886.

|

| Paul Bedford Elwell was born on 7th

February, 1853, in Albrighton, the second son of Wolverhampton

merchant, Paul Elwell. He was educated at King’s College, London where he obtained

a distinction in mathematics, and spent a year at Liège studying

coal mining and iron manufacturing. His wife Elizabeth was born

in Wolverhampton and in the 1881 census they are recorded as

living at "The Cottage", Ryton, Shifnal, Shropshire, with one

son, Paul L. Elwell, aged 7 months.

Paul Bedford Elwell's occupation is listed as 'the manager

of a works making nails etc., employing 100 hands'. By 1882 the

family had moved to St. Cuthbert's, Albrighton. The Commercial

Road Premises was rented from the owner; J. Smallman.

According to an article in the Birmingham Daily Post on 20th

July, 1864, what must have been the Patent Tip and Horseshoe

Company in Commercial Road, was placed in the hands of the

Elwell family after they loaned more money to the firm.

|

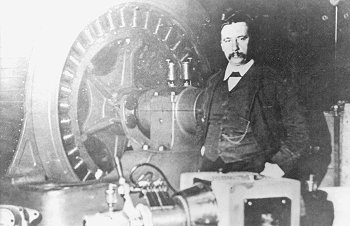

Thomas Parker and his dog. Courtesy of

Gail Tudor. |

| The manager was Alexander Stocker, previously of the

Bordesley Iron Works. In 1835 he acquired a patent for

his improved method of producing horseshoes. It seems

that Stocker founded the Patent Tip and Horseshoe

Company with money provided by the Elwells, on the

understanding that the horseshoes would only be supplied

to them. |

|

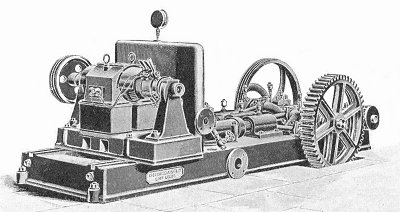

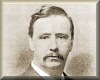

The surviving Elwell nail making

machine. |

In 1864 Charles and Paul Elwell dismissed Stocker

because of his absence from the business, and he took

them to court over the matter. In 1871 Paul Bedford

Elwell was clerk to the Patent Tip and Horseshoe

Company, and by 1876 was managing the firm. He took out several patents. The

first for nail-making machinery was registered in 1876,

the second, registered in 1878 was for shoe tips, and

the third, registered in 1879, was for Venetian

blinds.

What is almost certainly the only surviving Elwell

nail making machine was found in 2004 at the Crown Nail

Company in Commercial Road, where it had been in store

for over 100 years.

The machine has been rescued by the Black Country

Living Museum and is currently in store. Hopefully one

day it will be restored and put on display. It must be

one of the oldest, if not the oldest surviving British

cut-nail machines. |

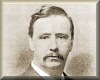

| Another view of the Elwell

cut-nail machine showing his patented oscillating feed

arrangement.

In a conventional cut nail

machine the steel strip from which the nails are cut is

turned over between each cut, to eliminate waste. This

involves a rotating feed mechanism, which is eliminated

in Elwell's design, by the oscillating feed. |

|

A drawing of another Elwell

cut-nail machine, also with an oscillating feed, which

can be seen on the left. |

|

An advert from 1871.

|

Initially the company had premises on the southern side

of the Crown Nail Company in Commercial Road. On 17th April 1882

Elwell purchased part of the large factory that stood on the

corner of Walsall Street and Commercial Road, on the other side

of the Crown Nail Company's works. Further space at the works

was acquired on 24th June.

In the early days, Elwell had little knowledge of electricity,

and so left that side of the business to Thomas. The new company

was housed in a corner of the Commercial Road works, the

electrical department staff consisting of Thomas, one of his sons and a man.

Dynamos were needed at the factory for lighting and for

charging accumulators. Unfortunately the dynamos used at the

works, like many of the dynamos available at the time, were

unreliable and not up to the job in hand. Thomas decided to

design an improved dynamo that would reliably and efficiently

provide power, both for the company's own needs and as a new

product. The first Elwell-Parker dynamo was completed in

October, 1883 and was a great success.

|

A view from 1954 of the offices of W. E.

Jones timber importers who occupied the site of the Elwell-Parker

factory. It could well be that the building was once the Elwell-Parker

offices. It is now long-gone. |

|

Thomas described his early years at

Wolverhampton, in a speech that he gave to the Directors of the

Liverpool Overhead Railway, on 7th January, 1893:

| As to our work at Wolverhampton, I may tell you that

Wolverhampton ten years ago had no thought of being guilty of

building dynamos, but there came a circumstance, that

circumstance being an individual, myself, who went to

Wolverhampton and thought that he could build dynamos. That was

October 1882.

I took with me my boy and began by employing one

man. We first built accumulators and afterwards began to build

dynamos. The first one built, I remember it well, it was a

waster, I thought, and it lay in the shop after I had tried it.

It did not do what I wanted it to do, but there was a difficulty

in Lancashire of coating calico printing rollers with nickel,

and Mr. Freemantle paid a visit to Wolverhampton to see what we

were doing. He was secretary of the Manchester Edison Company,

and he was also associated with some of the people who were

trying to cover their rollers with nickel. He said they had

tried every dynamo, and he came to ask me how to get over the

difficulty. I told him there was one there that could do what he

wanted, if it didn’t we would take it back.

We went to

Manchester; at first they could do nothing with it. On following

it to Manchester, I saw at once what they required, and in a few

hours I coated their rollers with nickel. I received a £40

cheque from Mr. Freemantle, with a testimonial, and that was the

first dynamo built in Wolverhampton, the year being 1883. I was

encouraged to build one for lighting, this was a success, and

got us an order for six. We received from the Manchester Edison

Company of that time, £1,000 in advance for building dynamos:

this was the beginning of Elwell-Parker, and of dynamo

manufacturing at Wolverhampton. |

|

|

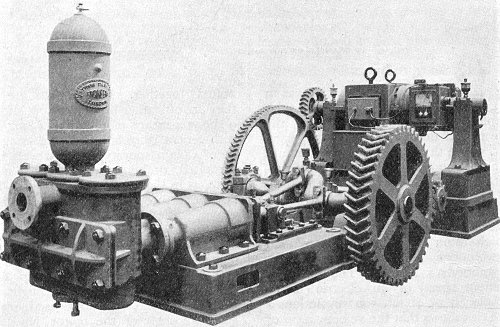

| In 1883, the company designed, built, and installed

dynamos and electric lighting for the Trafalgar Collieries

in the Forest of Dean. This was the first underground

electrical installation in the country, if not in the world.

The electrical equipment included a 1.5hp. motor that was

attached to a pump to lift water 300 feet from below the

surface. In the same year Paul Bedford Elwell was promoted

to captain of the local Rifle Volunteers. |

The Elwell-Parker motor attached

to the Greenwood and Batley pump as part of the

installation at Trafalgar Collieries. From the October

1902 edition of Feilden's Magazine. |

Another Elwell-Parker motor

fitted to a Greenwood and Batley pump. From the October

1902 edition of Feilden's Magazine. |

| |

|

| Read a description of

the Elwell-Parker accumulators from The Engineer

magazine |

|

| |

|

|

An order was also received for six dynamos from the

Manchester Edison Company, and they were paid a £1,000 in advance.

The rapid success of this part of the business overshadowed

horseshoe manufacture, which soon ceased; and in 1884 the company

became the Wolverhampton Electric Light, Power, Storage and

Engineering Company. This name was soon changed to Elwell-Parker,

Limited, after an infusion of fresh capital.

Mr. Parker made the acquaintance of Mr. Charles

Moseley of Manchester, through Mr. George Freemantle, who was then

the secretary of the Edison Company. Mr. Charles Moseley became

chairman of Elwell-Parker, who at the time employed thirty men at

the works in Commercial Road. By 1885 the amount of business had

increased to such an extent that considerable extensions to the

premises were necessary. Elwell-Parker accumulators were successfully

tested at the Bush Hill estate, near Enfield4

in 1883. This estate was a property development in which Elwell and

several relations had invested heavily. Unfortunately their

investment was not a success and they eventually lost a lot of

money.

|

The location of Elwell-Parker, Ltd.

|

| |

|

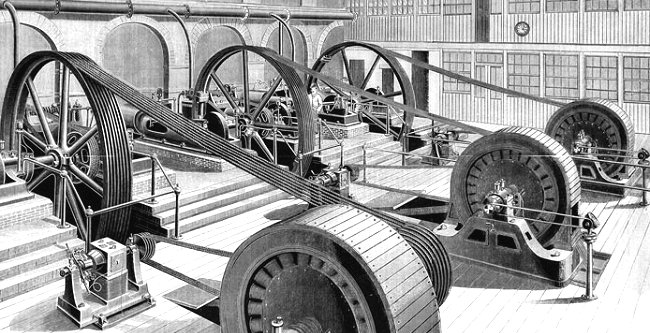

| Read about the steam engine

designed by Elwell and Parker to power their dynamos |

|

| |

|

An Elwell-Parker accumulator had also been in use

since 1882 at Elwell's home, St. Cuthbert's, Albrighton. In October

1885, Elwell described the effects of a lightning strike that had

occurred at the house, to the British Association in a meeting at

Aberdeen. From his description it was obvious that both Elwell and

Parker had done a first class job with their wiring. He told the

Association that he occasionally used one of his telephone cables

for the dual purpose of carrying power for lighting and receiving

operatic music from the theatre at Wolverhampton, which was a good

10 miles away.

In 1883 Paul Bedford Elwell is listed in

Crocker's Directory, as being the Managing Director of the Patent

Economic Coal Company, Limited, Commercial Road. He obviously had

other business interests than his partnership with Thomas Parker.

|

|

|

Thomas, surrounded by Elwell-Parker

products. In the background is a revolving field alternator, on

the right is a transformer and in the foreground a dynamo.

Courtesy of Gail Tudor.

|

|

The modern type of dynamo was developed by the

Belgian electrical engineer, Zénobe-Théophile Gramme, in Paris, in

1869. His D.C. generator used a ring armature, consisting of a coil

of wire wound on a ring of iron, which rotated in a two-pole

magnetic field. He patented the principle and effectively prevented

others from modifying his design until the patent ran out in 1884.

When the patent expired, dynamo manufacturers seized the opportunity

to produce a more efficient and cheaper machine, and Elwell-Parker

led the way.

In 1885 Sir William Preece, speaking before the

Royal Society of Arts, said that the revival of the electricity

industry in this country was due to the efforts and success of Mr.

Parker, and writing in the Royal Society of Arts Journal, he praised

Mr. Parker for winning a place for Britain in the fast developing

electrical industry. In the same year Thomas was made a member of

the Institution of Electrical Engineers.

|

The following is from 'The Engineer', 13th June,

1884:

Engineering at the Staffordshire

Exhibition

The machinery and industrial

sections in the Wolverhampton and Staffordshire

Industrial and Art Exhibition, which was opened on

May 30th, and will remain open until the end of

October, are well-filled with excellent specimens of

engineering and similar work. The buildings are

shortly to be lighted-up on the incandescent system

by the Wolverhampton Electric Light Engineering and

Storage Company.

The stand of Messrs. Crossley Brothers, Manchester,

who were represented by their Wolverhampton agent,

Mr. H. P. Lavender, contains a small "Otto," a

Parker-Elwell dynamo, and a Parker-Elwell, Planté

accumulator, all engaged in exhibiting on a small

scale, the incandescent system of domestic electric

lighting by Mr. T. Taylor Smith. The dynamo drives

twelve lamps of 20 candle power each. The Otto is of

½ horse power nominal and 1·9 horse power indicated,

and the dynamo has been made specially for that size

of engine. The arrangement is the same as that used

to light-up by several of the swan companies. Though

on a small scale, it is an object of much interest

to the visitors at night. |

|

|

Ellwell-Parker Limited displayed eleven dynamos

and an electric motor at the 1885 Inventions Exhibition at South

Kensington, and in the same year supplied dynamos for lighting to

the London Stock Exchange and Lloyds of London.

| |

|

| Read a detailed technical

description of the Elwell-Parker products displayed at

the 1885 Inventions Exhibition |

|

| |

|

Thomas continued his links with the Coalbrookdale

Company. Elwell-Parker Limited didn't have a foundry and so most of

their castings were made at Coalbrookdale.

|

|

One of the first large orders secured by the new company was for

the design and construction of the electrical plant for driving

the Blackpool Tramway, the first English electric tramway of any

size. The trams

used a conduit system, where the power was picked-up from a slot

between the rails. The conductor was composed of two

copper tubes of elliptical shape, attached to iron studs The

studs were supported in porcelain insulators, that were mounted

on blocks of creosoted wood in the sides of the channel. At each

end of the car there was a switch box, with resistance coils

placed under the platforms, by which means the strength of the

current and speed of the car could be regulated. |

|

|

A section of the conduit used at Blackpool. |

| To reverse the direction in which the car was travelling, the

direction of the current through the armature was reversed. The

shunt-wound field coils were always magnetised in the same

direction. Each car was driven by a single bipolar, reversible

motor, the drive being transmitted by an open chain to one of the

two truck axles. Work began

on the motors and dynamos in 1884. The first tram ran on 2nd

July, 1885, this was the first electric tram to run along an English

street.

The system was a great advance on any other electrically

powered transport system at the time. It did have some defects

however. Often at high tide, it was completely covered in water

and sand, when the wind blew in from the sea, and many times it

was under several feet of snow. The switchgear became crusted

with sodium and chlorine salts and so could be unreliable. |

| One of the

original trams still survives at the National Tram

Museum, Crich. It was converted to run on an overhead wire, and

ended its career as a service vehicle.

Originally Blackpool tram

number 3, it later became tram number 4. Thomas Parker remained

as the tram company’s consulting engineer until 18925. |

Blackpool tram number 4. |

|

The restored interior of

Blackpool tram number 4. This is typical of a public vehicle of

the day and is similar to what was used on many of the

horse-drawn trams. |

|

The underside of Blackpool

tram number 4. The original traction motor has been replaced,

only the end casting remains. The tram is chain driven as can be

seen from the sprockets, the chain having been removed. |

|

|

After the inaugural run, the Mayor of Blackpool

and his guests retired to a celebration dinner in honour of the

opening of the new tramway. After the meal speeches were given and

Thomas Parker said that the future of railways was with electric

traction. Electrically powered locomotives were cheaper to run than

steam and could travel at 70m.p.h.

| |

|

Read a detailed description

of

the installation at Blackpool |

|

| |

|

Thomas always took a keen interest in electro

chemistry and electro-metallurgy. When the Cowles process for the

manufacture of aluminium bronze was first introduced, he considered

the use of continuous current to be a mistake, and designed an

alternating current furnace, which when tried, proved to be a great

success. Later this would lead to a revolutionary way of producing

phosphorus.

Thomas developed a system of electro-deposition for the refining of

copper and the extraction of gold and silver. Elwell-Parker

made a notable contribution to the electrical purification of

copper, when their dynamos were installed at the Bolton Copper works

at Oakamoor, and revolutionised the purifying process.

|

|

In 1886, Nautilus, the first electric- powered

submarine, was invented by two Englishmen, Andrew Campbell and James

Ash. On the surface it was powered by two internal combustion

engines, but when submerged it was propelled by two 50h.p. electric

motors. They were powered from a 100 cell Electric Power Storage

(E.P.S.) battery, which could power the submarine for as long as

four hours, before recharging was necessary. The submarine achieved

a surface speed of 6 knots, and could cover 80 miles between battery

charges. In 1887 the submarine was fitted with an Elwell-Parker

E.P.S. battery.

|

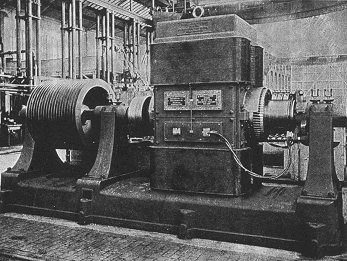

A large Elwell-Parker dynamo. |

| By this time, Elwell-Parker had supplied dynamos to several

local manufacturers including nearby Swan Garden Ironworks run

by John Lysaght, E. T. Wright and Sons at Monmore Ironworks, the

Staffordshire Steel and Ingot Iron Company in Bilston, and

George Wilkinson and Company at Tividale, for use in their sheet

mill. |

One of the dynamos supplied to the Great

Northern Railway.

| Elwell-Parker supplied three dynamos to the Great

Northern Railway which were used to supply power for lighting in

the locomotive works, and to charge accumulators. Two of the

dynamos had an output of 300 volts at 56 amps, at 840

revolutions per minute. They supplied current to 84 carbon arc

lamps. The third dynamo had an output of 130 volts at 120 amps,

at 880 revolutions per minute. It had a resistance coil

connected to the shunt winding in order to vary the output

voltage. It supplied power to incandescent lamps, and was also

used for charging accumulators. In between 1884 and 1887 Elwell and Parker took

out no less than 14 patents for electrical equipment, either

jointly or separately. Some of their other electrical

installations included Lloyd's offices in the Royal Exchange,

and Manchester Central Station. The "Electrician" for 28th

January, 1887, stated that "Messrs. Elwell-Parker have rapidly

come to the front rank of electrical engineers, and their

dynamos and motors are being widely used". |

|

Thomas designed and built multi-phase alternators

with a stationary armature and a revolving field of the salient

type. Salient poles were built-up from steel stampings, either

bolted or dovetailed to a frame. This type of design proved to

be very successful and was used for many years.

An alternator with a revolving field

and salient poles. |

|

In 1887 Mr. James Oddie of Ballarat, Australia,

came to England to obtain information on electrical knowledge and

its developments. He was a wealthy gold miner, who became Ballarat’s

first Chairman of the Municipal Council and

was greatly impressed with Elwell-Parker and their products. Whilst

here he visited Blackpool and his description of the trams was

printed in the Ballarat Star, on Friday, 18th

April, 1890. His description is as follows:

|

I had great pleasure in looking at the

esplanade, which is two miles long. It is lit up by nine arc

electric lights and an electric tramway system runs from end to end.

There are 10 cars on it, each capable of seating 55 or 60

passengers. In the summer season, when Blackpool (a favourite

resort) is crowded, 2d is charged for the journey from end to end;

in winter, when visitors are scarce, the same ride may be had for

1d.

This line is one of the sweetest things in

the empire. There is no jar, and the travelling is perfectly lovely.

The motive power in this case is picked up by conductors from an

underground conduit. Through my cousin (Mr. John Nixon, who is a

member of the council, who put up the lights) I had access to the

corporation members and officers and to the managing directors of

the Tramway Company.

While there I gave a dinner to the members

of the corporation and the tramway directors and officers; the mayor

of Manchester, Mr. Alex Siemens (nephew of the late Sir Wm.

Siemens), Mr. Thomas Parker (of Messrs. Elwell and Parker), and

other electricians were present. The dinner went very well and the

proceedings were characterised by enthusiasm. The manager of the

gasworks informed me that the electric light was cheaper than gas,

and that the latter was either 2s.6d or 2s.9d per 1000ft., certainly

not more than 2s.9d.

The electric tramway was so successful that in

the first year it paid a dividend of 5 percent. The second year it

just paid expenses owing to a mishap, the sea getting into the

conduit and partly filling it with sand, the

Job of removing which was most costly. The third year, when it

carried 950,000 passengers (mainly 2d fares), it paid 7 percent. It

is hampered by not being allowed to run on Sundays, while busses

are; otherwise it would beat all opposition.

The power used is obtained from a double set of machinery, two semi

portable engines (worked one at a time) and two Elwell Parker

dynamos, all models of beauty and economy, and which work like

clockwork. The line is a patent of a Mr. Smith, of Halifax, but its

success is mainly due to Mr. Parker.

|

|

In 1887 Thomas Parker developed a process for

the production of phosphorus, and chlorate of soda, by electricity,

which greatly reduced the manufacturing costs. The company also

manufactured alternators and supplied their generating equipment to

Eastbourne, Melbourne, South America, New Zealand, India, and many

other locations throughout the world.

Orders increased, and in 1887 the decision was taken to build

a large new works at Bushbury, on the outskirts of the town.

Land was acquired in Showell Road, but the project was delayed

because of the death of Mr. Charles Moseley, the company’s

Chairman, in October 1887.

On 15th December, 1887 the trial of an Elwell-Parker electrically

powered tramcar took place on the tramline from Wolverhampton to

Willenhall, which was only about 500 metres from the factory. This

must have been the first trial run of an electrically-powered

tramcar on a street in the West Midlands. The car, which had been

ordered by the Australasian Electric Tramways Company was designed

on the lines of the Julien accumulator system developed by Edmond

Julien of Brussels.

The tram was similar to a double-deck, four-wheeled,

horse-powered tramcar, except that the wheels were driven by a

single electric motor, mounted beneath the car, and coupled to the

wheels by gears. Power was supplied by a set of lead-acid

accumulators mounted beneath the seats, and accessible via doors on

the outside. A second trial took place on 4th January, 1888, and

another a short while later which was viewed by representatives from

several tramways, including Birmingham. The trials were a complete

success, and two tramcars, and two sets of batteries were soon

despatched to Australia. In September of that year, one of the cars

was demonstrated on the streets of Melbourne, and in Ballarat in

October.

An impression of the electrically-powered

tramcar.

The cars were ordered by Mr. Edmund Pritchard on behalf of the

Australian Company, and led to a legal battle between Mr. Pritchard

and Mr. H. G. C. Woods who had purchased the Australian rights to

the Julien patents. Mr. Woods had expected Mr. Pritchard to pay him

royalties on the patents, but Mr. Pritchard refused because the cars

were built in England under the terms of the English Julien patent

owned by Elwell-Parker, and not in Australia.

Elwell-Parker dynamos were used for many applications. In 1888

one was supplied Erith Ironworks to supply power to an electrically

operated crane. The dynamo provided a supply of 120 volts at 80

amps, at 1,200 revolutions per minute, and was installed in the main

boiler house.

After publishing a translation of Gaston

Planté's book "The Storage of Electrical Energy" in 1887, Paul

Bedford Elwell left the company. This appears to have been due to

two reasons, the forthcoming sale of the business to the Electric

Construction Corporation, and the large amount of debt incurred by the failure of his Bush Hill

estate investments. When questioned by an Australian parliamentary

standing committee in May 1890 about electric tramways, he stated

that "The business was sold to a company in a way of which I did

not approve, and I preferred to clear out."

He sold his house at Albrighton, and went to Paris to prepare

plans for the Paris underground electric railway. Soon afterwards

his bad luck continued. His wife Elizabeth, died of typhoid and he

left for Australia in the hope of finding suitable employment there.

He became Electrical Engineer to the New South Wales Railway

Commissioners, and was responsible for the electrification of Sydney

tramways. He played a leading part in the development of Sydney’s

tramway system, and its power station at Ultimo, the buildings of

which still exist as part of the Powerhouse Museum. Sadly he died

there on 10th September, 1899, at the early

age of 46.

| |

|

| Read Paul Bedford Elwell's

views on tramways |

|

| |

|

| Read Paul Bedford Elwell's

Obituary |

|

| |

|

Thomas Parker and the

motor car

Thomas must have been the first motorist in

Wolverhampton, if not in the UK. He claimed to have had an electrically powered

vehicle running as early as 1884 and developed many prototypes

during his lifetime. He religiously obeyed the Light Locomotive Act,

the red flag law, which was only banished in 1896. It set a speed

limit of 4m.p.h. in open country and 2 m.p.h. in towns. The Act

required three drivers for each vehicle, two to travel in the

vehicle and one to walk ahead carrying a red flag. One of his cars

gave over 18 months trouble free service on daily runs to and from

Tettenhall, to the E.C.C. works at Bushbury.

|

One of Thomas Parker's early cars outside

the family home; The Manor House, Upper Green, Tettenhall.

Thomas is sat in the middle and on the back seat is possibly his

son Alfred.

|

|

During a talk that he gave to the automobile

Club, he described the hilly town of Wolverhampton as being without

a single yard of level ground from Tettenhall to the town. He

groaned at the "Queen Square gradient", which was a real problem

when insufficient batteries limited his progress.

One of his cars

went to London and was shipped to Paris, but the ship floundered in

mid channel and his valuable car was salvaged and brought home. Some

of Thomas's vehicles had hydraulic brakes on all four wheels, as

well as four-wheel steering. These features are even now being

described as revolutionary.

|

An Elwell-Parker motor, driving a

stamping machine that was used for making jewellery at James

Harrison & Sons, Tenby Street, Birmingham. It is from a

catalogue that is in the collection at the Museum of the

Jewellery Quarter, Vyse Street, Birmingham. |

|

The initial Patent Tip & Horseshoe

Company's site on the eastern side of Commercial Road. |

|

The rear of the initial Patent Tip &

Horseshoe Company's site facing the canal. The remains of

their wharf can be seen on the right. |

|

|

Birmingham Trams

An order was received from the

Birmingham Tramways Company, for the design and construction

of a prototype electric tram, to run on their existing

system, which was operated by steam trams.

The steam trams were noisy and dirty, and a cleaner and

quieter alternative was required. The decision was taken to

test an electric tram on their system, which would hopefully

fulfil all of their requirements and also be more reliable

and cheaper to run than the existing trams.

It was decided that the tram must be self-powered, as overhead wires

were considered to be unsightly and a conduit system too expensive

to install. A battery-powered prototype was built and successfully

tested at Birmingham, on 7th

November, 1888. It was an instant success and Elwell-Parker expected

further orders.

| Read about the

successful trial of Birmingham’s first electric tram, and a

description of the proposed system |

|

Thomas was a director of the

Douglas Patent Clock and Electric Meter Company of Birmingham,

founded in 1888. The firm produced electricity meters.

One of Thomas's many patents was for a switch that automatically

switched between a battery and a dynamo, so that when the dynamo

ceased to operate, the battery was disconnected. When the dynamo

started again, and the voltage had reached its normal level, the

battery was reconnected to continue charging. It could also be

used in installations where the battery provided backup power

when the supply from the dynamo failed. The following is a brief

article describing the device:

|

From 'Engineering'

magazine, July 15th, 1888.

|

|

By 1889 the company had 400 employees, and the

works operated both day and night. In the same year Thomas Parker

became a member of the Institute of Civil Engineers and a rosy

future seemed certain for the company.

A drawing of the

Kensington Central Electric Lighting Station

from an 1889 edition of 'The Engineer',

showing a small Elwell-Parker dynamo in the

bottom left-hand corner. |

In 1889 Thomas Parker and William Low patented

the Lowrie-Parker dynamo. Several were supplied to Kensington

Electric Lighting Station. Also in 1889 a large syndicate was formed to

manufacture electrical equipment of the type already made by Elwell-Parker. The syndicate founded the Electric Construction

Corporation, Limited and purchased a number of prominent

manufacturing companies to form the new corporation. Thomas Parker

was invited to London in 1888, to meet Mr. Balfour, from the

Corporation, regarding the purchase of Elwell-Parker, Limited. Terms

were agreed and Elwell-Parker, Limited was absorbed into the new

concern, as from 30th September, 1888.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Early Years |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed to Australia |

|

|