|

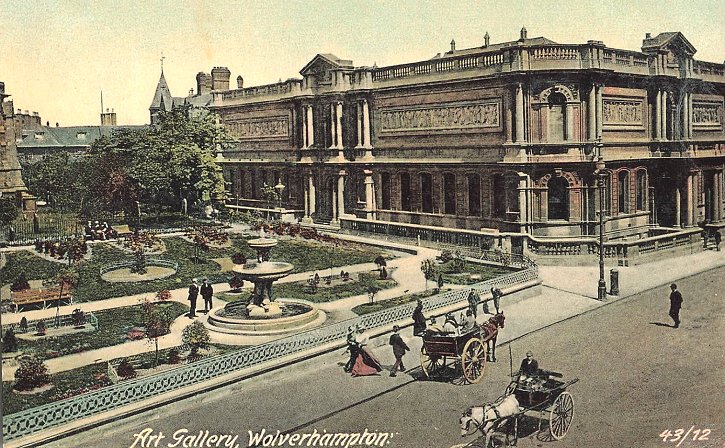

Listing: 1883-5. By J.A.Chatwin of Birmingham. Italianate style. Built

for the Wolverhampton Exhibition.

Literature: N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England:

Staffordshire, Harmondsworth, 1974 at p. 317.

Comment: The statement that it was built for the Wolverhampton

Exhibition is not a reference to the 1902

Exhibition. At the opening of this building, in 1884, there was a

large Exhibition of the Arts and Manufactures, in a temporary building on the

site of what later became the wholesale market, with a covered way connecting it

to the Art Gallery (see J. Jones, Historical Sketches of the Literary

Institutions of Wolverhampton, London, 1897). This art gallery was

certainly not built "for" that Exhibition.

The building is the only public building erected on Lichfield Street when

that street was widened. It was mostly paid for by Philip Horsman, a local

builder (who,

inter alia, built the town hall), who also did the building work here.

A fountain in St. Peter's gardens, just off the left of the photo, commemorates

this worthy's contribution to the town and is said to be erected by the grateful

townspeople. Horsman was a genuine benefactor (though some might think he

had only got the money in the first place by paying his men too little) and

liked to keep quiet about his munificence.

The upper floor has no windows, a sensible provision when the main

requirement is internal wall space on which to display painting.

So the upper galleries are top lit by windows hidden behind the parapet.

And the external blank walls are saved from aridity by having reliefs on

them. According to G. T. Noszlopy and F. Waterhouse, Public

Sculpture of Staffordshire and the Black Country, Liverpool

University Press, 2005, the sculptor was Richard Lockwood Boulton and

Sons of Cheltenham, (Presumably the executed designs by the

architect, Julius Alfred Chatwin).

|

A detail of one of the panels on the side wall of the upper

storey (which decorate the blank walls which the galleries on the upper floor

require) depicting local industries. Here squeaky clean, immaculately dressed

and magnificently coiffed gentlemen engage in a bit of metal bashing.

|

According to Noszlopy and Waterhouse the figures on the

two panels on the side of the building personify Industry and the

Sciences. There are seventeen figures representing industry and

they include a glass maker, a book binder, a stonemason, wrought

iron workers, locksmiths, a potter and a designer. The figures

representing Science include architecture, geometry, medicine,

chemistry, geography, engineering and navigation.

| One of the two panels on the front wall, depicting

Roman ladies engaged in suitably feminine artistic activities. |

|

|

The other panel on the front wall, with Roman gentlemen

engaged in artistic activities. |

According to Noszlopy and Waterhouse the left hand panel

shows women personifying pottery, painting (three figures), drawing,

music, literature (two figures); and the right hand panel shows nine men

personifying sculpture.

The inclusion of a designer on the side panel is

interesting as it is unusual to see design considered separately from

other industrial activities and more likely to have been in the arts

panel, if it appeared at all. The presence of design in this panel

is likely to be related to the history of the Art School, which, under

the influence of Loveridge and Mander, and George Wallis of what later

became the Victoria and Albert Museum, was the earliest school of design

outside London.

| Originally the art gallery went back as far as the start of

the portico, seen in the photo above. The portico and the part beyond

was a separate building and was the art school. The two buildings were

separate enterprises. But when the committee which ran the art school

discovered that the new art gallery was proposed they muscled in on the act.

The council gave the land for both buildings and, although Horsman paid for

the art gallery end, the art school end was paid for by Horsman buying the

old art school buildings in Darlington Street for £2,000 and the Jones

brothers, John and Joseph giving £1,000.

S. Theodore Mander gave £250

and Henry Loveridge gave £200: they had been subsidising the art

school for years. Other donations were made and the government gave a

grant of £1,000.

It is obvious that the same architect was used for both

buildings and the building work doubtless went ahead as one. |

|

|

Financing the school and the gallery gave rise to

problems. The city council was already funding the Free Library

(and running classes there - an operation of marginal legality) and that

used up all the expenditure they were, by law, allowed for these sorts

of activities. They therefore had to promote an Act of Parliament

to allow them to raise money to pay for the art gallery and art school.

This was approved at a public meeting, sent forward to Parliament and

passed in to law on the 8th August 1887 (The Wolverhampton Corporation

Act 1885, 50 & 51 Vict. cap. clxxiv). |

It is interesting that the

Act refers to the School of Art and Science: the significance of this is

debatable. The Act authorised the council's setting up a Gallery

of Art and School of Art and Science Committee to run both buildings.

It seems that, from the start the Head of the Art School was also the

Curator of the Art Gallery. The science courses offered seem

to have been limited to Building Construction and Drawing; Machine

Construction and Drawing; and Architectural Design.

At the time the art gallery and the art school together were

seen not just as having a role in cultural enlightenment and moral uplift

but also as having a role in industry and commerce because of the

contribution they would make to industrial design. The critic, Charles

Whibley, writing in 1887, had an interesting view of the contributions these

buildings might make: "In few towns in England was an art-gallery so

imperatively required as at Wolverhampton; for, speaking frankly - to

a stranger at least - it is a dismal place. It contains neither noble

streets nor important buildings. We even look in vain for the trim

villa; and it is evident that the wealthier inhabitants live as far off as

possible from the factory chimneys, which obtrude themselves on us

everywhere, veiling the sky and seeming to blacken the surrounding

landscape. A picture gallery at the centre of such a town as this is

an inexpressible relief, and cannot fail to exercise a beneficial influence

on the inhabitants. It is to be hoped moreover that material additions

will be made to the collection of examples of the lesser arts, which at

present is but scanty; the practical advantages accruing from the

study of design and handicraft will then be directly manifested".

This art gallery is one of three such facilities in the

city. The Bilston Craft Gallery is a regional gallery which exhibits

craft work from the region, Bantock House is the local history museum and

this building, the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, is the place for the visual

arts. The basis of its collection was gifts made at or shortly after

the building's opening by Sidney Cartwright, Philip Horsman and Paul Lutz,

James Beattie and others (totalling some 50 paintings). The Jones Brothers

also gave £1,000 for acquisitions. A few years later Mrs Marie Christian

Cartwright bequeathed the collection (of about 275 paintings) she and her

husband, Sidney, had accumulated over the years; it was valued, at the time,

at £17,000 - a lot more than the cost of the building. Probably

because of George Wallis' connection with the town, the gallery in its early

years also received a collection of material from the V & A, including

Elkington electrotypes.

In a review of the art gallery published in the Magazine of

Art in December 1887, Charles Whibley mentions that there were some works by

modern artists and some genre paintings; but, he says, the collection

is particularly strong in the art of forty years ago - when British art was

uncompromisingly British and "untouched by foreign influence" - and

therefore contains many wonderful landscapes.

Now the art gallery occupies the original building and the

part behind (which was originally the art school) and the brick building

beyond that (which was originally an addition to the art school). The

two main galleries on the upper floor house displays of Victorian art and of

Georgian Art, with a commendable attempt to put them into a social context.

In the Victorian collection the gallery claims to have the UK's finest

collection of the Cranbrook Colony of painters; and it also has works by

many Victorian standards such as Landseer. In the Georgian collection

- which was greatly augmented in the 1970s by grants from the V&A - there

are works by Gainsborough, Zoffany, Fuseli, Wright of Derby and others.

The gallery is also strong on 20th century art, the basis of

which is the collection given by Anthony Twentyman and an unusual acquisition

policy in the 1960s. There are painting by Lichtenstein and Warhol and

much pop art.

From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

The art gallery used also to contain an exhibition of local

history; some of this has now moved to the excellent local history museum in

Bantock House. The rest is presumably in storage somewhere and really

ought to be on display somewhere - anywhere.

The gallery has often been in periods of doldrums, mostly caused

by funding shortages, interspersed with periods of enterprise. A short period

when the gallery put on extremely enterprising exhibitions, such as "One for the

Pot" - a history of tea drinking, complete with waitresses in Victorian dress,

serving afternoon tea in a palm court - is well remembered.

In recent years the exhibitions have been the expected

touring exhibitions and local art shows, and occasional locally curated

shows of more than a little enterprise and imagination. Currently the main,

original, galleries are about as well, and as inter-actively, set up as may

be.

The building is currently nice and clean on the outside and

rather well and appropriately decorated inside. During most of 2001 the

gallery was closed for a good deal of refurbishment and additions.

These were said to be needed to meet modern requirements; but they

were also needed to stop the rain getting in. The galleries were not

much changed but the storage and working areas were.

| In 2003 funding of £6.7 million was obtained from various

sources to build a brand new set of flashy glass and steel

galleries in what is currently the back yard. This was due

to start in April 2004 but, of course, did not. It

eventually got going in January 2005 and was opened in 2007.

The back of the original part was most unattractive and it faced

a desolate and scruffy courtyard. The new galleries had to

fit in with the Georgian and Victorian red brick buildings to

each side and make the best use of the old courtyard space. The

external appearance which resulted is about as good as could

have been expected, once a misguided proposal to cover most of

the exterior with a memorial to the Lunar Society of Birmingham

had been fought off. |

|

Inside the part

which was the old Art School has been changed beyond recognition and new,

high spec, galleries added. They look pretty good. Their main purpose

is said to be to display the gallery's large collection of Pop Art and this

is expected to draw art students and enthusiasts from far and near.

One waits and, so far, one does not see.

Some people held the view that the best feature of the

art gallery was the excellent cafe. As part of the work on the

extensions the cafe was rebuilt, on two levels, and in the best glass

and steel type of modern design. It is now once again the best

feature of the gallery.

|