| There was a time not that long

ago, when parts of Wolverhampton constantly rang to the

sounds of industry, and night skies were ablaze with

light from numerous factories and furnaces. Today most

of our factories have gone and it’s hard to imagine what

life was like in the industrial era. One of our oldest

factories is the Crane Foundry, which occupies a foundry

site that dates back to the late 18th century.

The foundry is situated alongside the

canal and originally had its own basin. Many foundries

were built close to a canal to use the readily available

supply of water to cool their cupolas. With the opening

of the canal in 1772 the area became heavily

industrialised and for the first time raw materials

could easily be transported here and finished goods

taken away. Its early neighbours included T. & C.

Clarke’s Shakespeare Foundry, which opened in 1795; the

Shrubbery Iron Works, founded in 1824; Isaac Jenks &

Sons’ Minerva and Beaver Iron, Steel, & Spring Works;

the Osier Bed Iron Company; and the Horseley Fields

Chemical Works.

|

| By 1827 the foundry was known as

Atherton’s Foundry and run by James Atherton and Henry

Crane. Initially it was a brass foundry, but by 1827

iron castings were also produced on the site.

The main products were castings for

the building industry, ironmongery and brassware. In the

1830s castings for the hand tool and lock industries

were added to the product range and by 1836 Henry Crane

had taken control of the business. |

|

|

The Foundry in 1842. |

The company became known as the

Crane Foundry in 1847 with its own registered trademark.

By the 1850s iron weights were

produced, and a design was registered in 1872 with

roundels decorating the edge. Brass weights were also

produced, mainly after the regulation of 1890 that

required weights of 2oz. or less to be made of brass. |

| A look at the 1881 census reveals

that the Crane family lived at Lower Street, Tettenhall.

Charles Henry Crane ran the business

and was aided by his two sons, Edward and Charles. At

the time the foundry had 150 employees.

Edward was a member of the

Wolverhampton Chamber of Commerce and became President

in 1902. |

The registered design of weights

with roundels.

|

|

Read about the

moulding and

casting process |

|

The foundry in 1919.

|

|

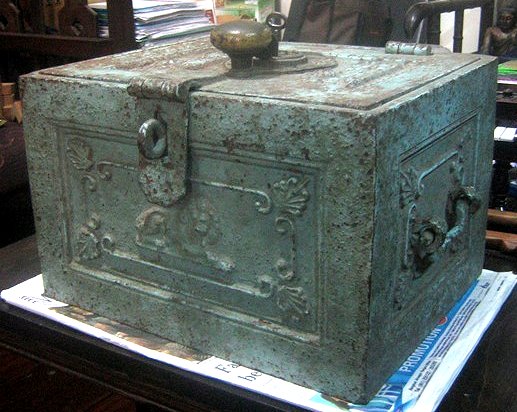

A Crane Money Chest. Courtesy of Marlena Fairbourne. |

In the early 1900s the foundry

began to produce castings for electric motors and

continued to do so throughout its life.

The Crane family

continued to control the company until 1917 when William

Cyril Parkes of lockmakers Josiah Parkes & Sons Limited,

Willenhall became a majority shareholder, with the

immediate result that the production of lock cases

greatly increased.

One of the lock-related products from the late

1920s is shown opposite. It is a cast

iron Crane Money Chest. You can still see the

original green paint in places. |

|

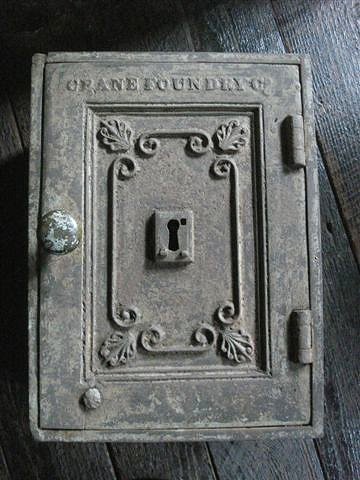

Another view

of the Crane Money Chest.

Courtesy of

Marlena Fairbourne. |

|

|

A lovely Crane Money Chest

that found its way to Burma.

Courtesy of

|

| Another view of

|

|

|

A close-up view of the

maker's plate that's on the front of

|

|

A look at the company’s 1928

catalogue reveals over 300 products including weights,

rice bowls, sad irons, ventilators, mole traps, door

knockers, and hinges.

|

View the 1928

Crane catalogue |

|

|

|

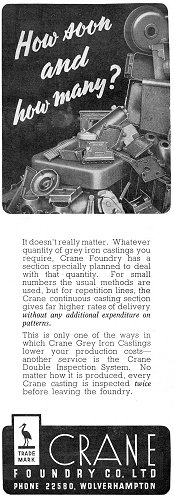

An advert from "Machinery"

30th June 1933. |

An advert from the "Electrical

Times" 20th April 1938. |

An advert from 1938.

|

|

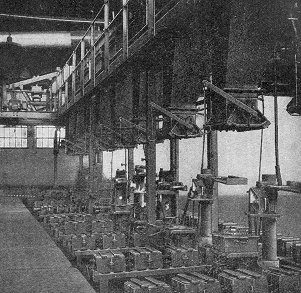

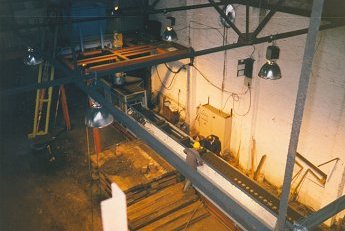

A corner of the works in 1938. |

The company began to specialise as a supplier of

castings to engineering companies, as can be seen from

the above adverts. Crane brand metalware eventually

became a thing of the past and this change in direction

helped the foundry to survive long after all of it's

local competitors had gone. By April 1937 the

metalware catalogue consisted of just five pages,

whereas the 1928 catalogue had 77 pages. The principal

metalware products in 1937 were box irons, heaters, sad

irons and weights. |

| Qualcast

On 25th June, 1945 Josiah

Parkes & Sons sold the foundry to Qualcast for £9,200

and in 1949 the foundry was officially called Qualcast

(Wolverhampton) Limited. The Crane trade mark was still

retained and the factory continued to be known as the

Crane Foundry. The company also owned the nearby Swan

Gardens Iron Works off Swan Street.

A staff social evening in 1949.

Courtesy of Crane Cast.

Another photograph of the event.

Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

An advert from the mid 1950s. |

Production at the Crane Foundry concentrated on

light repetition work for the engineering industry. Grey

castings were produced, weighing from a few ounces to

half a hundredweight. Castings were supplied to vehicle

manufacturers, gas and electric cooker manufacturers,

hand tool makers, and lockmakers. Castings were also

made for electric motors, lawn mowers, sewing machines,

typewriters, washing machines, telephone equipment, and

conveyor rollers for the mining industry. The Swan

Gardens foundry opened in 1953 and produced larger

castings from 0.5 to 3 hundredweights for motor cars,

commercial vehicles, farm tractors, stationary engines,

electric motors, refrigerators, and domestic water

heaters. |

|

Some of the smaller castings made

at the Crane Foundry. |

| Things started to go wrong during

the recession of the 1970s when many of the country’s

foundries closed. Qualcast was hit hard by a series of

industrial disputes and the Swan Gardens Foundry lost a

lot of orders due to the recession in the tractor

industry, which resulted in the workforce being reduced

from 420 to 280. The work’s output fell from 500 to 290

tons per week and this proved to be unprofitable, with

the result that the Swan Gardens Foundry closed on 24th

June, 1972. Luckily the

Crane Foundry survived and the company decided that the

foundry's future could be secured by increasing sales to

mainland Europe. A 2,500 mile round trip to Sweden was

organised as a cost exercise to see if it would pay to

make regular deliveries to the continent. The trip also

included deliveries to existing customers to show that

the company meant business. |

|

The lorry sets off on its 2,500

mile European trip.

General Manager R.M. Lackner shakes hands with driver

Arthur Lloyd and colleague Geoff Walker. Courtesy of

Crane Cast. |

The lorry left Wolverhampton on 23rd November, 1972

and took the ferry to Gothenberg in Sweden. After three

days travelling around the country visiting customers,

they took a ferry to Germany from where they drove to

France. After making deliveries to French customers they

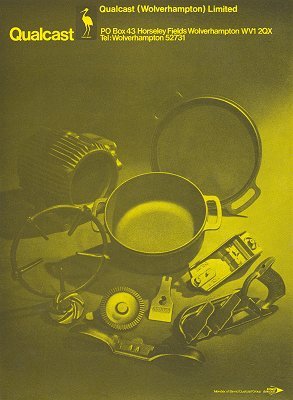

returned to Wolverhampton via Dover. Qualcast also

produced a range of casseroles and frying pans that were

designed by Robert Welch. After some hard negotiating

and advertising the products were exported to America,

Australia, Denmark, France, Germany and Sweden. |

| The lorry arrives at A-B

Vibro-Verken in Solna, Sweden.

Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

|

One of the deliveries in

France.

Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

View the foundry in

Qualcast days |

|

View some of the Qualcast

products |

By 1978 Crane Foundry employed around

600 people and produced 300 tonnes of castings per week.

The foundry specialised in intricate thin section

castings made to BS1452:1977 Grade 180 within a weight

range of 0.03kg to 35kg. Castings were made for the

automotive industry, gas cookers, multi-fuel stoves,

domestic appliances, and general engineering. |

| Foundry closures continued and

most of the factories in the Qualcast group disappeared.

Crane Foundry itself was threatened with closure but

saved by the intervention of Managing Director Mr. Roger

Lackner, who purchased the unprofitable company. The

works were severely over-manned and a rationalisation

programme initiated. Unfortunately the redundancy costs

were so high that even with a healthy order book,

liquidation soon followed. |

The installation of the new

cupolas in 1995. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

|

The cupola control equipment is

lifted into position. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

Receivers were appointed in 1985

but Mr. Lackner managed to buy the company from the

receivers with financial backing from Crane’s two

largest customers, Stanley Tools and Brook Motors.

The new company was renamed Crane

Foundry (Wolverhampton) Limited with a workforce of just

over 130. |

| The new company’s future looked

bright under the leadership of Roger Lackner and his son

Mark. A Disamatic automatic

moulding machine was installed to increase production

and the maximum weight of the castings increased to 100

kilograms. |

|

Examining the cupola control

equipment. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

|

|

Installing the Disamatic moulding

machine in 1995. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

Further improvements followed in

1995 when the company embarked on a 2.5 million pound

investment programme to ensure that the foundry was

technically and environmentally viable.

A second Disamatic moulding machine

was installed to double the work’s capacity and two 8

tonne per hour Dozamet cold blast cupolas with full fume

cleaning were added to increase iron production and

comply with the Clean Air Acts.

|

| The cupolas are mechanically fed

with scrap metal, limestone and coke, and water-cooled.

The cupolas were designed so that each can work on

alternate days when the other is de-clinkered, stripped

of its clay lining and re-lined in readiness for use.

The tuyeres are fed by fan-blown air and the speed of

flow of the molten metal can be varied by changing the

air pressure. The temperature, air flow and water

cooling are precisely monitored by an electronic PLC

control system. |

The Disamatic control panel is

lifted into place. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

The Disamatic machine from above.

Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

A Birlec electric induction

melting furnace was installed as a reservoir for the

cupolas, which also allowed two grades of iron to be

used at the same time. The Disamatic moulding

lines can produce up to 300 castings per hour and the

foundry's automated track can produce 150 moulds per

hour.

|

| The heavy moulding line is capable of 30 moulds per

hour and in-house facilities were set up for shell

cores, cold box cores, CO2 cores and a new

four tonne annealing oven. Box sizes are 600mm x 480mm

on the Disamatic lines, 660mm x 460mm on the automated

line and 760mm x 760mm on the heavy moulding line. The

castings vary in weight from 0.5kg to 80kg and grey iron

can be produced to BSEN 1561 Grades 180, 200, 220, and

250. |

The Disamatic machine in

operation. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

|

A fresh ladle of molten metal in

readiness for casting. Courtesy of Crane Cast. |

|

The Core Shop,

Fettling Shop, Dressing Shop, and the main foundry were

greatly improved and a steady stream of new customers

followed.

Sadly, even

after all of the investment the company remained

unprofitable and the workforce was reduced to 68. |

| For a while Crane Foundry became part of British

Steel, but the foundry went into

receivership again on 21st

September, 2000. Luckily funding was found and the

company reformed itself as Crane Cast. |

Casting on the Disamatic machine.

Courtesy of Crane Cast.

|

|

|

View the foundry as it was

in 2005. |

Things seemed to be going well until

the company’s liabilities spiralled out of control. The

recent rise in electricity and gas costs, and the loss

of two of the company’s largest customers, meant that

the directors had no choice other than going into

liquidation in January 2006.The company and

workforce had fought hard to survive, but too many

things went wrong at once. A sad end for one of

Wolverhampton’s oldest companies.

I would like to thank Rebecca, Kevin and Mr. S.

Reacord of Crane Cast for all of their help in producing

this brief history. |

|

Return to

the museum |

|