| Introduction

This article is designed to enable a non-specialist to

appreciate the churches of one architect, working in a

modern style and developing that style over the course

of about thirty years. The individual churches are

described in the order in which they were built but to

visit them in that order would necessitate an

undesirably zigzag journey. However, whichever one you

start at it would be helpful to read about his earlier

designs first.

Richard Twentyman

|

|

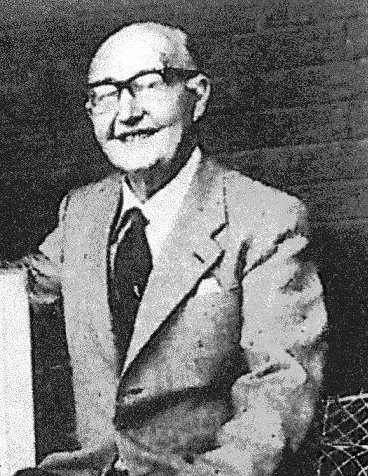

(Alfred) Richard Twentyman was born in 1903 at the

family home, Bilbrook Manor House. His father was a

director of the family import/export firm but was also a

Master of the Worshipful Company of Turners; his mother

was a talented cartoonist; and his younger brother,

Anthony, became a famous artist and sculptor of the

Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson generation.

Richard took a degree in engineering at Cambridge before

going on to study at the Architecture Association in

London, a body which was cutting edge then and still is.

Twentyman would have been fully exposed to new trends in

architecture there. In 1933 he joined up with H. E.

Lavender who was already working in Wolverhampton.

The

firm was responsible for many buildings in and around

Wolverhampton for which Twentyman was the design

partner. These buildings included Beatties extension in

Darlington Street, the former gas showrooms on the

corner of Waterloo Road and the A & E department of the

Eye Infirmary. |

|

The

firm won a RIBA bronze medal in 1953 for the GKN research laboratories in Lanesfield and a

Civic Trust commendation for offices in St John’s

Square. They designed pubs for W Butler & Co, as well as

a number of private houses.

Twentyman’s abiding legacy, however, is the series of

churches, and one crematorium, which he designed and

built in the West Midlands area – plus a church in

Runcorn and another crematorium in Redditch – between

the 1930’s and the 1970’s.

Richard and Anthony continued to live in the family home

at Bilbrook until 1958 (it was then demolished) and then

shared a house in Claverley. Through his brother Richard

got to know artists of the day like the sculptor Donald

Potter and the painter John Piper who were commissioned

to produce works for Twentyman churches. Richard died in

1979.

Shortly after his death tribute was paid to him at

Wolverhampton Art Gallery in an exhibition of his

paintings and drawings. His picture of ‘Windmill and

Pigeon Loft, Sedgley’ is still held there. The catalogue

at the time described his work as generally ‘retaining

within it some mystery rather than being too

literal…combining a naïve charm in style with a

surrealist’s eye for subject details.’

Modernism

The

great church architects of the Victorian and Edwardian

eras designed their churches to reflect the pervasive

movement in theology at that time. The influential

Anglo-Catholic movement wanted to return to a mediaeval

view of the church with an emphasis on the mass/eucharist/communion

and a stronger separation of the functions of priest and

laity. So the altar was pushed back into a deep

sanctuary, in some cases behind a screen. And the

architects adopted the mediaeval style of church

architecture: Gothic, with the familiar soaring stone

spires, steeply pitched roofs, pointed arches supported

on shafted pillars with decorated capitals, windows with

twisting tracery, and ornate furnishings. In many of

them darkness was almost a virtue, with dark materials,

stained glass windows and gloomy side aisles.

In the

1930’s, however, a new style of architecture swept into

Britain inspired by German émigrés who had been building

in the radically new style since the turn of the century

especially at the Bauhaus Institution. New buildings in

Holland and Scandinavia also influenced British

architects.

The

new style was characterized by strong vertical and

horizontal lines and large areas of a single material

such as brick, concrete or glass. Architects using the

new style were keen to make a clean break with the past

– no borrowing from previous styles whether Gothic or

Classical. This was encouraged by the new style being

applied to whole new types of buildings such as cinemas,

power stations, department stores, suburban electric

railway stations, apartment blocks, showrooms for

motorcars and electrical goods, and the headquarters of

the BBC.

Church

architects soon took up the new style, though they still

had to work within limitations: the layout of a church

is largely dictated by what is happening in it, and

certain materials are thought more appropriate than

others – it would be hard to imagine a church with a

steel girder frame and acres of glass like Peter Jones’s

pioneering department store in London! But one of the

interesting things about Twentyman’s designs is how he

was able over time to move away from the traditional

view of what a church should look like.

What

are we looking for in Twentyman churches?

|

● |

A composition of a few simple blocks

making a bold and severe shell. |

|

● |

Increasingly imaginative ways to

introduce natural light into the interior

space. |

|

● |

A bold, sometimes stark use of materials:

stone in slabs on walls and floors so we can

admire its texture, colour, hardness – not

because it can be carved into foliage;

rendering left with a rough texture and dull

colour; copper for roofs because it goes a

uniformly pale green as it weathers; brick

on vast, flat exterior walls. |

|

● |

Decorative effects usually involving the

repetition of simple shapes - a row of

square windows or circular ceiling lights; a

pattern of repeated diamonds in wood or

stone; frequent use of closely spaced

vertical lines in wood, stone and glass. |

|

● |

The careful placing of works of art as part

of the design scheme - a fine sculpture or a

beautiful stained glass window. |

The Churches

From

the point of view of design Twentyman’s churches fall

into three periods:

|

● |

The two built just before the Second

World War: St Martin, Parkfields in

Wolverhampton, and St. Gabriel, Fullbrook in

Walsall. |

|

● |

The five built in the 1950’s: All

Saints, Darlaston; The Good Shepherd,

Castlecroft in Wolverhampton; St. Nicholas,

Radford in Coventry; Emmanuel, Bentley in

Walsall; St. Chad, Rubery; plus Bushbury

Crematorium in Wolverhampton. |

|

● |

The two built in the 1960’s: St. Andrew,

Runcorn and St. Andrew, Whitmore Reans in

Wolverhampton; plus Redditch Crematorium

built in 1973. |

Descriptions of the

churches:

|

|

St. Gabriel's, Fulbrook, Walsall, and St. Martin’s, Parkfields, Wolverhampton. |

|

All Saints, Darlaston, Bushbury Crematorium,

Wolverhampton, Church of the Good Shepherd, Castlecroft,

Wolverhampton, Emmanuel Church, Bentley, St. Nicholas,

Radford, Coventry, and St. Chad's, Rubery. |

|

St. Andrew's, Runcorn, St. Andrew's, Whitmore Reans,

Wolverhampton, and Redditch Crematorium. |

| A summary of his work

In the journal of the Royal Institute of British

Architects for April 1980 Twentyman's former colleague,

John Hares, wrote this appreciation:

He had a great ability quickly to appreciate the

essential elements of any programme and marshal them

into a plan of great clarity. By unending attention to

detail he would then develop this into a finished

building that was always elegant, well mannered and

never dull. His work deserves study by anyone interested

in the course of architecture in

the last 45 years.

Text by John Wallbridge 2011. Drawings

by Steve Rayner, David Billingsley, and

Susan Wallbridge.

The author would be delighted to receive

more information about Richard Twentyman. |

|

|

Return to

the menu |

|