|

By 1851 Walsall's population had more than doubled since

the beginning of the century, rising from 10,399 in 1801 to

26,816 in 1851. This was typical of most of the towns in the

Black Country because large numbers of people moved into the

area seeking employment in the many local industries.

Inevitably this led to overcrowding, poor living conditions,

and poor sanitation. All of which had to be dealt with in

the fullness of time. Convicts on the Loose Frederick

Willmore describes an interesting incident in his 'History

of Walsall' which took place in the winter of 1843. The

'Albion' coach was transporting a gang of convicts through

Walsall on their way to Portland prison. As the coach made

its way along Bloxwich Road, the horses took fright near

Pratt's Bridge and dashed at full speed into the centre of

the town. In Park Street the coach collided with the

carriage belonging to Mr. Perks, the sheriff's officer.

It overturned and killed the coachman, and Mr. Illidge, Deputy

Governor of Chester Gaol. In the confusion that followed,

the convicts were supplied with files by some friendly

people in the crowd. They continued their journey, and on

the way managed to liberate themselves. At Dunsmore Heath

they overpowered their guards, set the horses free, and

fled. Although most were recaptured, two were never found.

The incident led to other, and safer means of transporting

criminals from one place to another.

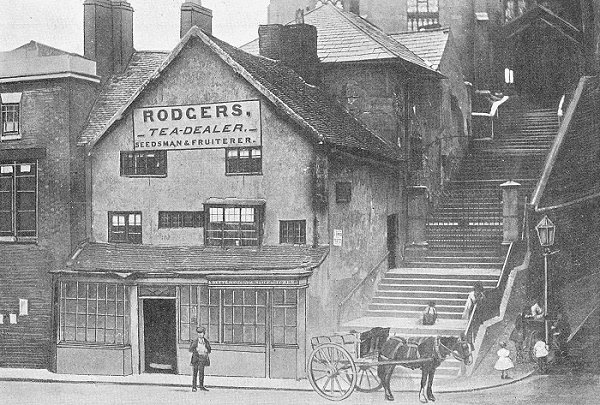

Upper Rushall Street and St. Matthew's

Church steps. From the 1899 Walsall Red Book. By the late

1890s, Rogers' shop had been demolished and

replaced by a fine building that survived until

around 1950. |

The

Mechanics’ Institute

The Mechanics’ Institute opened in 1839

in Freer Street with around 100 members, under the

presidency of Richard James, who is listed in White’s

Staffordshire Directory of 1851 as a merchant and factor,

with a business in Bridgeman Place. The institute was

founded to improve the mechanical skill, and the moral

character of the working classes, and consisted of a library

and a reading room. The annual subscription was ten

shillings. Sadly it had a short life, after becoming

embroiled in local politics, even though it was a

non-political and non-sectarian organisation.

The institute was openly supported by

radical Walsall Liberal M.P. Francis Finch of The Hollies,

Great Barr, a banker with a business in Bridge Street. The

institute’s secretary was Joseph Hicken who became secretary

of the Political Union for Walsall in 1830, and secretary to

the Anti-Corn Law League in 1838. The Corn Laws, introduced in 1815 were hated by many because they only

benefitted landowners, and caused a great increase in the

price of corn. The local Tories, who supported the Corn

Laws, were determined to destroy the institute, and refused

to allow their employees to become members.

After two years the membership had

fallen to 35, and after incurring a considerable amount of

debt, the institute closed in November 1841.

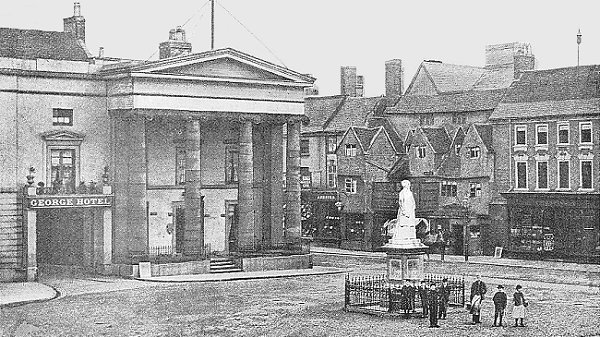

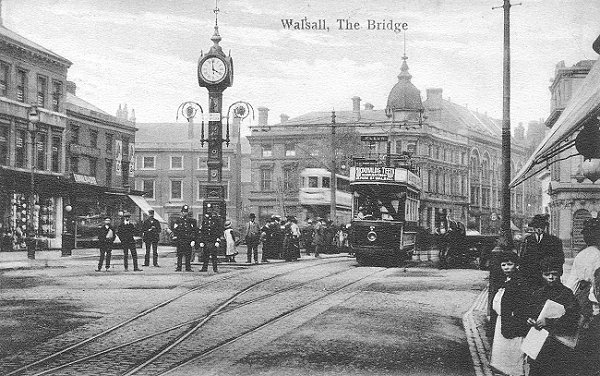

The Bridge. From W. Henry Robinson's

Guide to Walsall, 1889.

Swimming Baths

Walsall’s first public baths, the

Vicarage Water Baths in Dudley Street, opened in 1850, and

stood on the site of St. Matthew’s Quarter Car Park,

opposite Bath Street, which was named after the baths. The baths

were established by Thomas Gameson, with water from the

natural springs known as ‘The Spouts’. The building

contained a swimming bath, a shower, and several slipper

baths. It opened on week days from six o’clock in the

morning until nine o’clock in the evening, and on Saturdays

from six o’clock in the morning until ten o’clock at night. There was an unsupervised

department for men, and a ladies department with a female

attendant. The water was steam heated and kept at a suitable

temperature. In 1856 the proprietor was D. Rapp.

Each day was divided into first class

hours and second class hours. First class hours were from

nine o’clock in the morning until five o’clock in the

afternoon. Tickets were on sale as follows:

| First class for a

single hot bath |

10d. |

|

| First class for a

shower or swimming bath |

6d. |

|

| First class for

children |

4d. |

|

| Second class for a

single hot bath |

8d. |

|

| Second class for a

shower or swimming bath |

4d. |

|

| Second class for

children |

3d. |

|

In the middle years of the nineteenth

century when few houses had access to running water,

washing and personal hygiene was often neglected. Public

baths played an important role because for many they

were the only place where it was possible to have a

proper wash. Elias Crapper's baths in Littleton Street

which opened in the 1860s, and survived for around 30

years, was very popular and often extremely crowded.

In 1896 the Corporation opened the

Central Baths in Tower Street. The building was designed by

Walsall architects Bailey & McConnal, and included a

swimming baths, slipper baths, medicated baths, and Turkish

baths. It survived until 1959 when it was demolished to make

way for the Gala Baths which opened on 6th May, 1961. The

new baths were built at a cost of £380,000 and include a

competition pool 110 feet long and 45 feet wide, with

seating for 800 spectators, a brine pool and training pool

75 feet long and 30 feet wide.

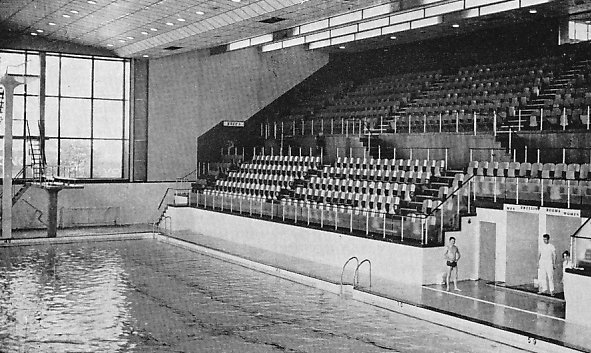

The Central Baths in Tower Street.

From an old postcard.

The Central Baths in 1914.

From the 1899 Walsall Red Book.

An advert from 1935.

The Gala Baths in the early 1970s.

In 1922 the Corporation built an

open-air swimming pool, 75 feet long, and 36 feet wide in

Field Close, Bloxwich. Slipper baths were added in 1923, and

in 1932 a building with an overall roof was built around the

pool. There was a remedial bath service, and a covering for

the pool, so that in winter months the building could be

used for dances, plays, boxing matches, wrestling,

receptions, and parties etc.

An advert from 1935.

Slum Clearance

Walsall like most of the surrounding

towns had its fair share of slums. In 1852 and 1853 the old overcrowded

slum properties on Church Hill were demolished under the

terms of the 1824 Improvement Act which gave the Corporation

powers to pave, light, clean, and widen the streets, and to

improve the town. The old Free School and the Market House

built in 1809 were also demolished and the area around the

church was opened out.

Large scale demolition of the town’s

many slums became possible after the passing of the 1875

Artisans’ and Labourers' Dwellings Improvement Act passed by

Benjamin Disraeli's Government. The terms of the Act gave

local authorities the powers to buy slum areas, and replace

them with decent housing. The Act compelled owners of slum

dwellings to sell them to the local authority, who had to

provide compensation. The dwelling would then be demolished,

and replaced with decent housing.

Demolition began in an area of 9,000

square yards at Town End Bank, and parts of Station Street,

Wolverhampton Street, Green Lane, and Marsh Lane, which

contained some of the most squalid slum properties in the

town. The district was insanitary, and unhealthy, and some

of the residents were described as idle, profligate, with

associations that are disgusting to public morality, and

common decency. The compulsory purchase of the land cost

£17,750.

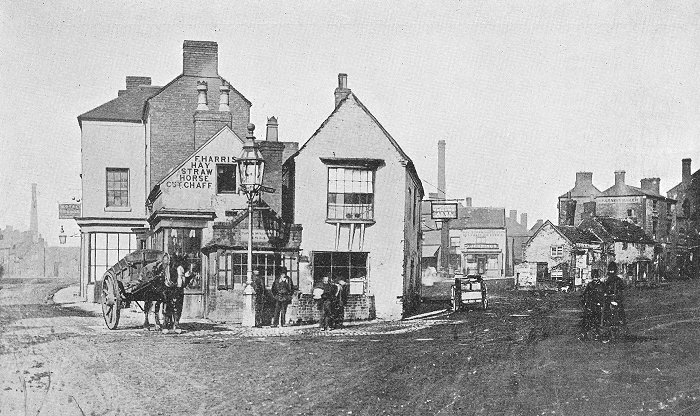

Town End Bank before demolition. From

the 1899 Walsall Red Book.

| |

Number |

|

Occupant |

Number |

|

Occupant |

Number |

|

Occupant |

|

1. |

|

John Holden |

15. |

|

William Johnson |

29. |

|

William Hughes |

|

2. |

|

John Twist |

16. |

|

Samuel Mason |

30. |

|

Jas. H. |

|

3. |

|

William Jackson |

17. |

|

William Wilkinson |

31. |

|

John Hunt |

|

4. |

|

George Harly |

18. |

|

Richard Jeffrys |

32. |

|

Joseph Lander |

|

5. |

|

Abigail Jackson |

19. |

|

Widow Spink |

33. |

|

Moses Walker |

|

6. |

|

Dorothy Holden |

20. |

|

John Spink |

34. |

|

R. Athersmith |

|

7. |

|

The Pound |

21. |

|

John Osborn |

35. |

|

Widow Johns |

|

8. |

|

Thomas Adams |

22. |

|

George Somery |

36. |

|

Edward Johns |

|

9. |

|

Elizabeth Green |

23. |

|

Thomas Lilly |

37. |

|

Thomas Nicolls |

|

10. |

|

Iona Brooke |

24. |

|

Nicholas Fly |

38. |

|

Thomas Adams |

|

11. |

|

John Palmer |

25. |

|

John Merry |

39. |

|

J. Lisby |

|

12. |

|

William Green |

26. |

|

J. Athersmith senior |

40. |

|

Thomas Fly |

|

13. |

|

Widow Lander |

27. |

|

J. Athersmith jnr. |

|

|

|

|

14. |

|

Thomas Adams |

28. |

|

Thomas Hughes |

|

|

|

In 1871 Dr. J. MacLachlan produced a

report for the Improvement Commissioners which was published

in the Walsall Free Press and South Staffordshire Advertiser

on 9th September, 1871. The report included the following

extract:

There are many buildings in the town

which are old and dilapidated and totally unfit for human

habitation. In many cases these ruinous tenements are so

close together as to constitute an obstacle to proper

ventilation; and the only remedy is to clear the ground and

let fresh air in.... The houses however, are in a

dilapidated condition and are quite unfit for the purpose to

which they are devoted. The floors are rotten and full of

crevices affording shelter to vermin and dirt.... In the

kitchen of one of them, in which there were a number of

people and in which cooking had to be done, I found a

corpse, and this is not the first time such an occurrence

has come to my notice. I would recommend the establishment

of a public mortuary to which the person dying in lodging

houses or other crowded dwellings might be removed to await

internment.

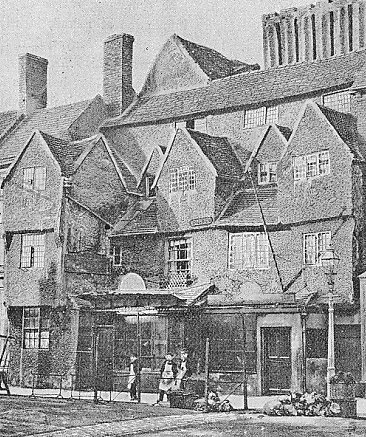

Old buildings in Digbeth. From

W. Henry Robinson's Guide to Walsall, 1889. |

| Smaller slum areas were cleared under the

terms of the 1875 Public Health Act which was designed to

combat filthy living conditions, that could lead to the

spread of diseases such as cholera and typhus.

The areas

cleared included courts and alleys in Bull’s Head yard,

Church Hill, The Ditch, Dudley Street, Peal Street, and

Lower and Upper Rushall Street.

Although some of the worst slums had

been removed, many more remained. Overcrowding and

insanitary living conditions were not uncommon, particularly

in the poorer areas, where there was still a lack of sewers,

a lack of proper drainage, and an insufficient fresh water

supply.

There would be no large scale redevelopment until

after the First World War when the 1919 Housing Act came

into force. This actively encouraged local authorities to

build new houses, and provided financial incentives. |

|

In the 1880s articles appeared in local

newspapers describing the terrible living conditions endured

by many of the poorer families. In January 1888 the Walsall Free Press

and South Staffordshire Advertiser included an article

describing the wretched conditions amongst the poor in the

Wisemore district. It gave an insight into the poor housing

conditions in the area, and the suffering endured by many.

| Read

about the poor conditions in the Wisemore

district |

|

In 1885 to 1887 there was a serious

trade depression which affected the whole of the Black

Country and led to high levels of unemployment. The winter

of 1885 to 1886 was extremely cold and severe, and greatly

added to the suffering of the poor. A soup kitchen was

established at St. George's Road Church Schools which opened

on 13th February 1886, and operated until late March when

the snow had disappeared. Each day thirty gallons of soup,

and a small supply of tobacco was available for adults, and

whenever possible, dinners of soup and jam pudding were

given to children.

|

St. George's Soup

Kitchen

Walsall Observer - March 27th,

1886

By means of

the Soup Kitchen established at

St. George's Road Church

Schools, and worked by the Vicar

and his Committee, a large

amount of help has been given to

the suffering poor. The first

distribution was on the 13th of

February, and up to Saturday

last there had been twelve

distributions, each of thirty

gallons making a total of 360

gallons. In addition dinners of

soup and jam pudding were given

to children on six occurrences,

the number of little ones thus

being provided for being 792.

Adults dinners had been given

three times and the number

provided for was 405. To the men

present on these occasions a

small supply of tobacco had been

given out. In addition to this

dinners had been served in other

school rooms. The snow had now

disappeared but it was still

found that there were very many

in great distress receiving no

Saturday wage. It was decided to

continue the children's dinners

if the necessary funds were

supplied. |

|

Although the situation improved in the

late 1880s, things went from bad to worse in the 1890s when

a severe trade depression throughout the country resulted in

a large number of unemployed people. The depression started

in 1893 and lasted for two years, during which time the

government set up a Select Committee to investigate the

extent of distress caused by the lack of employment. Walsall

Corporation responded by giving employment to as many people

as possible who could assist in sweeping the streets, and

clearing away snow etc. Sadly this proved to be totally

inadequate, and so the Mayor, J. Noake convened a meeting of

the inhabitants and started a relief fund, based on

voluntary subscriptions. The sum of five hundred and sixty pounds was

raised, and tickets were issued to people requiring relief.

The maximum allowed to a single family was 10s.6d per week.

Loaves of bread, and grocery tickets were also handed out.

In 1893 the Medical

Officer of Health wrote a report on public health in the

town. At the time there was a high death rate of 24.42

per 1,000 of the population, and the deep trade

recession led to many tradesmen being unable to properly

support their family. The rise of poverty, leading to

poor living conditions greatly helped the spread of

diseases such as smallpox, scarlatina, diarrhoea, and

typhoid. The report concluded that overcrowding was

still a serious problem which could not be remedied

until the return to full employment.

| |

|

| Read about local

hospitals |

|

| |

|

Newspapers

Walsall’s first newspaper, the weekly

Walsall Courier and South Staffordshire Gazette appeared in

1855, with an office in New Street. It appears to have been

short-lived, but was soon followed by the Walsall

Miscellany. In 1856 the Walsall Free Press and South

Staffordshire Advertiser came into existence. It ran until

1903 when it was taken over by the Walsall Observer.

Other newspapers appeared around the

same time including the Walsall Herald, the Walsall Guardian

and District Advertiser, the Walsall Standard, and the

Walsall News, which became the Walsall Observer. In 1857 Mr.

Robinson issued the Walsall Advertiser.

In January 1861 Walsall printer W. H.

Tomkins produced the weekly Walsall Herald, which survived

for 12 months, and in 1868 John and William Griffin founded

the weekly Walsall Observer and South Staffordshire

Chronicle which became the town’s most successful newspaper.

One hundred years later it was the town’s only surviving

newspaper. Unfortunately in the early years of the twenty

first century its fortunes wavered, the number of staff was

greatly reduced, and in 2009 its owners, Trinity Mirror,

decided to end publication.

An advert from 1896.

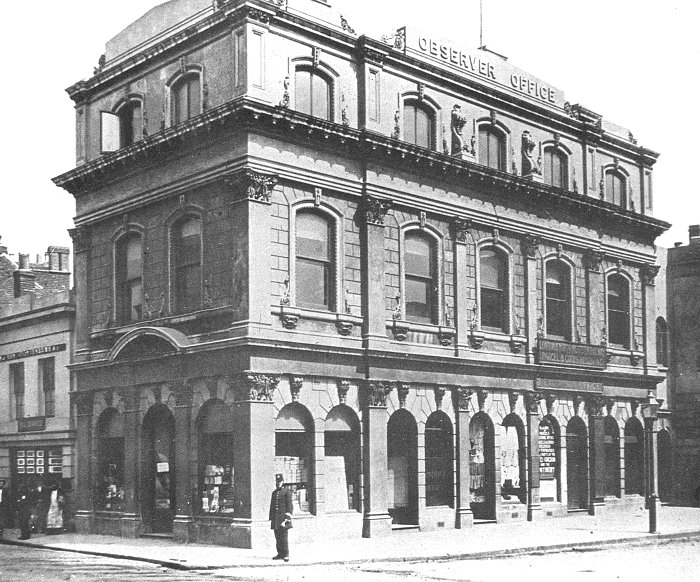

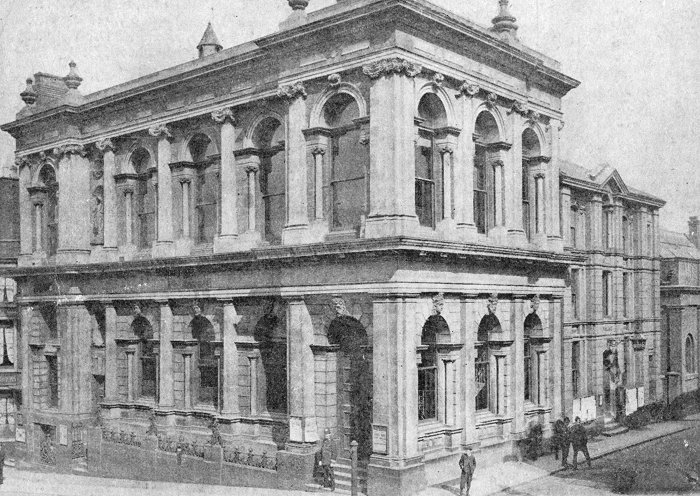

The Walsall Observer building on The

Bridge.

An advert from 1896.

Park Street. From an old postcard.

A New Workhouse

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 led

to the formation of Poor Law Unions, each with a central

workhouse. The unions were administered locally by Poor Law

Guardians who were elected by the local ratepayers, and

inspected by the Poor Law Commission, later called the Poor

Law Board.

The Walsall Poor Law Union was formed

in 1836 and operated across an area of 31 square miles,

which included the whole of Walsall, Aldridge, Bentley,

Darlaston, Great Barr, Pelsall, and Rushall. The Central

Union Workhouse was built in Pleck Road at a cost of £7,600.

It opened in 1838, and could accommodate 350 people. The

workhouse was enlarged in 1881 to cater for 464 people, and

in 1896 a separate 130 bed infirmary was added.

In 1867 Dr. J. H. Stallard produced a

damning report for the Lancet on the conditions in Walsall

Central Union Workhouse. It was published on 9th November,

and was not only critical of the workhouse itself, but also

of past inspections which had given it a clean bill of

health.

| Extracts from Dr.

J. H. Stallard's report on the workhouse |

|

The workhouse also had facilities for

the able-bodied poor who could work in the adjacent

stone yard, or oakum sheds. The hours were long, and the work

was arduous in the extreme. Workers in the stone yard were

paid at the following daily rate in 1886:

| Single

men |

8d. |

and 2lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife |

8d. |

and 4lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 1 child |

10d. |

and 4lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 2 children |

1s. |

and 4lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 3 children |

1s. |

and 6lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 4 children |

1s. |

and 8lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 5 children |

1s.2d. |

and 8lb. of bread |

| Man and

wife and 6 children |

1s.4d. |

and 8lb. of bread |

An advert from 1902.

Jerome K. Jerome

One of Walsall’s most famous sons,

Jerome Klapka Jerome was born in Bradford Street on 2nd May,

1859. He was a journalist and writer who is best remembered

for his novel ‘Three Men in a Boat’.

Jerome’s father the Rev. Jerome Clapp,

renamed himself Jerome Clapp Jerome. He came to Walsall from

Appledore, near Bideford where he had been minister of the

Congregational church. In Walsall he was an ironmonger, and

a deacon at Bridge Street Congregational Church. He later

conducted services when the congregation moved to the

assembly room in Goodall Street, and designed their new

church in Wednesbury Road.

From an old postcard.

Jerome was the fourth child of Jerome

and Marguerite Clapp. He had two sisters, Paulina and

Blandina, and one brother, Milton, who died at an early age.

It was a poor family, mainly because of his father’s bad

investments. He attended St Marylebone Grammar School in the

City of Westminster, but had to leave his studies to find

work after loosing his father at the age of 13, and his

mother two years later. He initially worked for the London &

North Western Railway, collecting coal that fell from the

trains, and then unsuccessfully tried his hand at acting.

After a number of jobs, he wrote a comic memoir about his

time in the theatre, which met with some success.

In 1888 he married Georgina Elizabeth

Henrietta Stanley Marris, and along with Elsie, her daughter

from a previous marriage, they honeymooned on a little boat

on the River Thames. When they returned home Jerome

immediately began to write Three Men in a Boat, which was

published in 1889, and became an instant success. Although

he wrote many other novels, essays, and plays, he could

never recapture that success again.

In the First World War he served as an

ambulance driver in the French Army after being rejected by

the British on account of his age. Sadly his stepdaughter

died in 1921, and in 1926 he wrote his autobiography ‘My

Life and Times’.

|

The blue plaque. |

|

On 17th February, 1927 shortly before

his death, he was presented with the Freedom of the Borough

of Walsall.

In June he suffered a terrible stroke, and died

two weeks later in Northampton General Hospital.

His ashes

are buried at St. Mary's Church, Ewelme, Oxfordshire where

he had a farmhouse. Elsie, Ettie, and Blandina are buried

beside him.

Belsize House, on the corner of

Bradford Street, and Cross Street where he was born, carries

a blue plaque.

His initial K is short for Klapka,

named after an Hungarian refugee who stayed with the family

for a time, and became his father’s friend.

|

Cemeteries

By the 1850s St. Matthew's graveyard

was full, and St. Peter’s was waterlogged, so urgent action

had to be taken. The Burial Acts of the 1850s gave local

authorities the power to establish municipal cemeteries, and

so the local authority acquired around 13 acres of land in

Queen Street, and in 1857 opened Queen Street Cemetery, the

first municipal cemetery in the town. It closed in 1969 and

is now remembered as the last resting place of Sister Dora.

It is now managed by Lifelong and Community Services.

In 1873 the council acquired six acres

of land off Field Road in Bloxwich and opened a cemetery

there. It has since grown, and now covers over sixteen acres.

In 1894 the council opened another

cemetery at Ryecroft which had separate mortuary chapels for

Anglicans, Roman Catholics, and Nonconformists. A

Crematorium opened on the site in October 1955. It closed in

1984 and was replaced by Streetly Crematorium.

A New Guildhall

|

The Guildhall. From an old

postcard. |

In 1865 work began on the new Guildhall in

High Street after the demolition of the

previous building. The new hall was designed

by local architect

G. B. Nichols who

had previously worked on The Beeches Estate in West

Bromwich, and designed Walsall’s Free Library in Goodall

Street. The laying of the foundation stone

took place on 24th July, 1865. The builder was Mr. Burkitt. The building was completed

in December 1866, in time for the inaugural banquet on 1st

January, 1867. It had cost £5,308. The building, which is

Grade II* Listed has been extensively renovated. |

|

The Guildhall in about 1914.

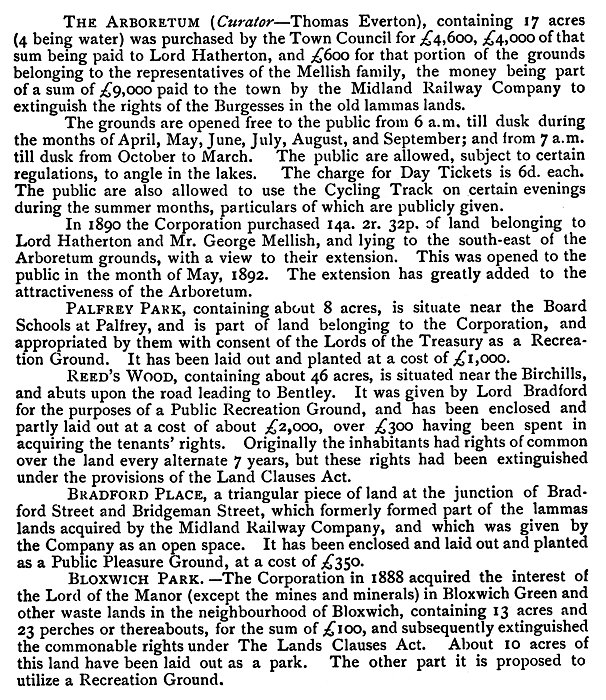

Public Parks and Recreation Grounds in 1899:

Walsall Arboretum

Walsall’s grandest park, the Arboretum,

was set up by the Walsall Arboretum and Lake Company,

founded in 1870 to turn the area of flooded limestone pits

into an arboretum, public, and pleasure grounds. The company

had a starting capital of £4,000, and in March 1873 took a

99 year lease from the landowner Lord Hatherton for the lake

above the flooded mine workings, and seven acres of adjacent

land. The plan was to build an arboretum and gardens with

facilities for amusements such as boating, fishing, archery,

and croquet etc. There would be a lodge, a boat house, a

bandstand, toilets, and an ornamental garden through which

visitors could walk.

The Arboretum. From an old postcard.

The grand opening ceremony took place

on 4th May 1874, when the park was officially opened by Lady

Hatherton in front of 4,000 people. Unfortunately the

venture was not a commercial success, and the company went

into liquidation in 1877. Although Lord Hatherton and a

group of local businessmen took over after the company’s

demise, the venture was still unsuccessful.

Due to public demand the Council agreed to take it over as a

public park, and in 1884 purchased the freehold for £4,000.

It officially reopened on 21st July, 1884. In 1890 the

council acquired another 13 acres from Lord Hatherton to

extend the park, which were opened to the public in 1892.

|

Walsall Arboretum

and

Lake Company Limited

Terms of

Admission

| 1. |

Annual

Family Ticket, to admit subscriber

and members of his family, except

gentlemen over 21 years of age; and

also his servant when in attendance

on the subscriber or his family, but

so that

the number of persons to be admitted

by such ticket must not be more than

8. |

£1.1s.0d. |

| 2. |

Annual

Family Ticket to admit not more than

5 persons, including servant on the

above conditions.. |

15s.0d. |

| 3. |

Annual

Season Ticket to admit 2. |

10s.6d. |

| 4. |

Annual

Single Ticket. |

7s.6d. |

| 5. |

Single

Admission on all days in the week,

but one special day. |

2d. |

| 6. |

Children under 10 years of age,

accompanied by an adult. |

1d. |

| 7. |

Special

days, the prices charged to be at

the discretion of the Directors. |

|

When required, Family

Tickets will be issued to include more

persons than those above specified on

payment of 2s. for each person.

The Annual Tickets will

date from 1st of May. |

|

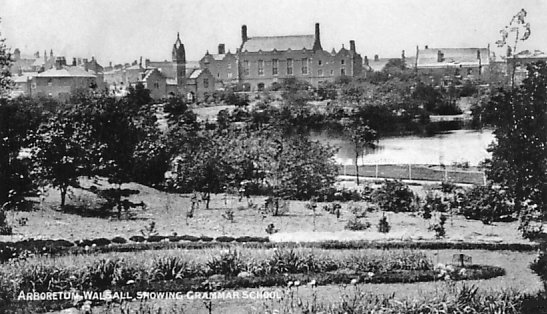

The Bradford Street entrance to the

Victorian Arcade in the early 1900s. From an old postcard.

Societies and

Institutions

In the nineteenth century a large

number of societies and institutions were formed to bring

like-minded groups of people together, with a common interest such as

art, literature, music, or science, and hopefully improve

the intellectual life of the town.

One of the earliest was the Walsall

Literary Society, founded in 1836. Another, the Walsall

Literary Institute, founded in 1884 was one of the most

successful, with a large number of members. It replaced an

earlier, but short-lived literary institute that was formed

in 1876 and met weekly at the Borough Club in Freer Street.

The Institute met in the Temperance

Hall in Freer Street, and provided lectures and talks given

by experts in such things as art, literature, music, or

science, and also organised social gatherings. There was

also a comfortably furnished reading room in Bridge Street,

supplied with the best periodicals and magazines. In 1891 it

moved to Lichfield Street. The Institute, which survived

until 1910, also gave grants to the Temperance Hall, and to

the Science and Art Institute.

The principal musical society in the

town was the Walsall Philharmonic Union, established in

1863. It had around 200 members and gave concerts in

conjunction with the Literary Institute at the Temperance

Hall. Rehearsals were held on Monday evenings, under the

control of the conductor, Dr. C. Swinnerton. In 1880 the

society merged with the Walsall Choral Union. Another

musical society that met at the Temperance Hall was the

Walsall Orchestral Union, formed in 1884. Meetings were held

on Tuesday evenings in the committee room.

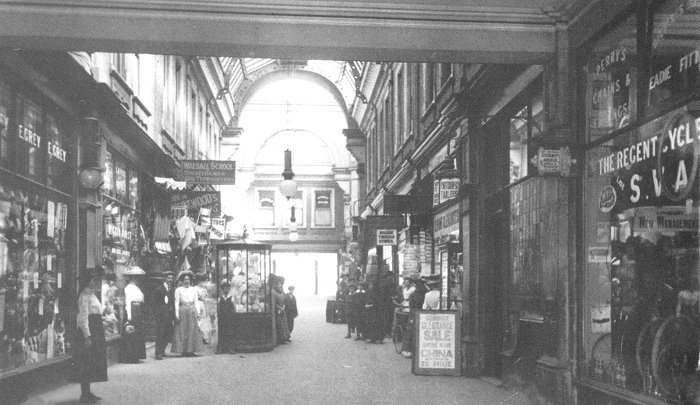

All Saints' Church, Bloxwich. From W.

Henry Robinson's Guide to Walsall, 1889.

Another society that promoted art,

literature, music, and science was the Institute Society,

formed in 1883. Meetings were held at the Science and Art

Institute, and present and past students were encouraged to

join. The society met on the second and fourth Thursday in

each month to listen to a lecture, or a paper given by one

of the members, followed by a discussion on the topic.

Horticulture was not forgotten. The

Florist Society formed in 1879 attempted to encourage the

growth and cultivation of flowers, fruit, and vegetables

amongst the working classes. It held an annual exhibition in

St. George’s Hall that attracted a lot of entries. In 1888

there were 681 entries, and £41.18s.6d. in prize money.

Walsall in 1889.

Chamber of Commerce

The Walsall Chamber of Commerce held

its first meeting on 2nd September, 1881. It has done much

for the trade of the town, and in its early years used its

influence to improve the postal service, to oppose increases

in railway rates, and to promote parliamentary schemes that

benefitted local industry. In the 1880s it was managed by a

president and council consisting of sixteen elected members.

Further Education

Early examples of further education

classes were the mutual improvement classes run by groups

such as the Bridge Street Mutual Improvement Society, formed

around 1860 to run classes in the schoolroom of Bridge

Street Congregational Chapel, the Walsall Wesleyan Mutual

Improvement Society, the Walsall Church of England

Institute, and the Butts Working Men's Institute. There was

also the Ablewell Street Science Institution which used the

schoolroom in Ablewell Street Wesleyan Methodist Chapel.

Technical education began in 1854 with

the formation of the Walsall School of Design and Ornamental

Art, founded by local sculptor, W. Smith. 1869 saw the

formation of a Government School of Art in Bridgeman Place,

which in 1871 moved to rooms in Railway Chambers, Station

Street. In October 1872 the school merged with the Ablewell

Street Science Institution to form the Walsall Science and

Art Institute, with Sir Charles Forster, M.P., as President.

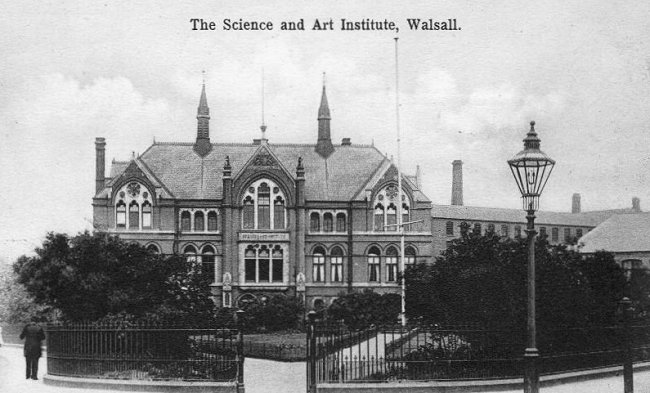

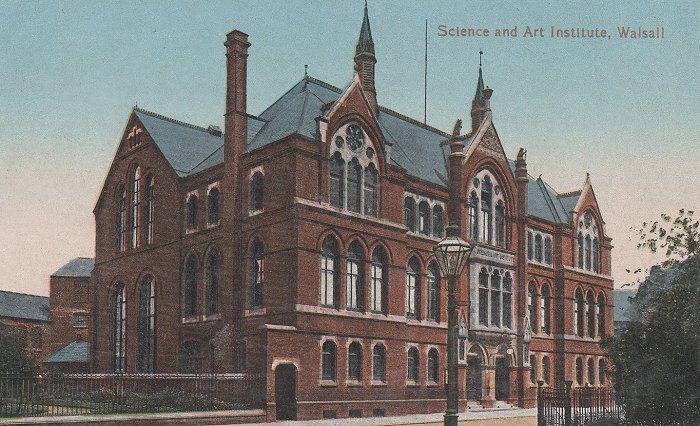

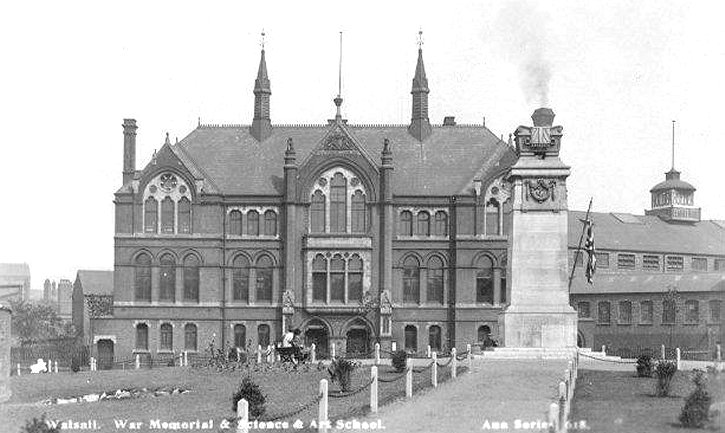

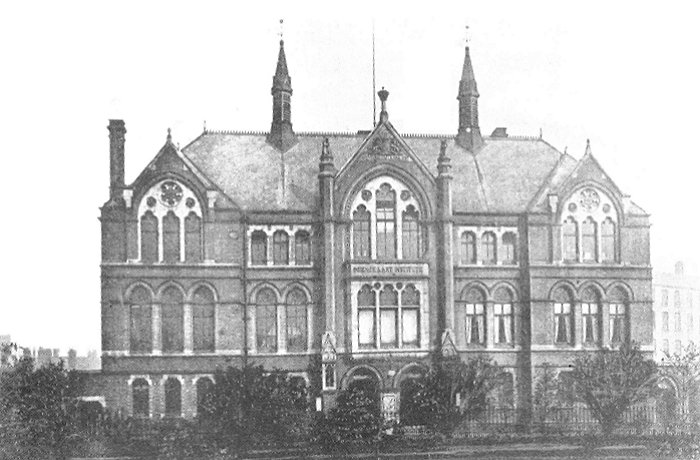

The Science and Art Institute. From W.

Henry Robinson's Guide to Walsall, 1889.

|

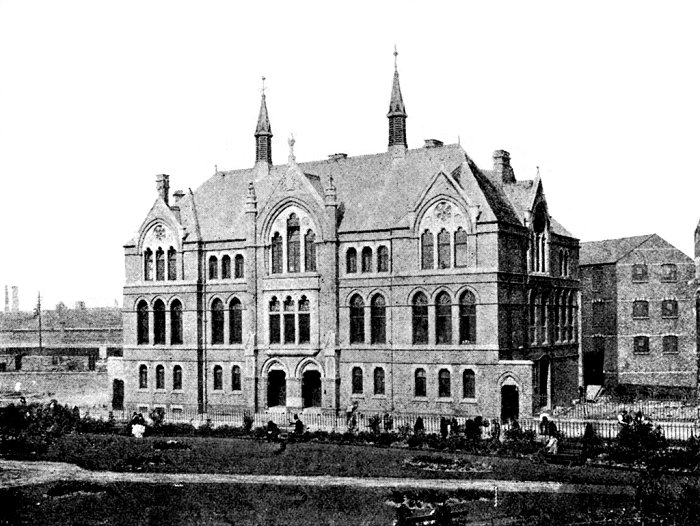

The Science and Art Institute. From an

old postcard. |

The institute struggled for some years

with insufficient funds, but help was at hand in 1887 thanks

to an unconnected gesture by the Prince of Wales, who

championed the building of a grand institute in London, to

be known as the Imperial Institute. Walsall’s Mayor, William

Kirkpatrick, wanted to emulate the Prince’s example by

building a grand institute in Walsall to commemorate Queen

Victoria's golden jubilee. He knew about the plight of the

Science and Art Institute, and suggested that a suitable

building should be erected in the town to house the

institute.

Land in Bradford Place was given by

Lord Bradford, and the foundation stone was laid on Jubilee

Day, 20th June, 1887 by the Mayor. The attractive and nicely

balanced building was designed by Dunn and Hipkins, of

Birmingham, and cost around £6,000. The opening ceremony, on

24th September, 1888 was performed by local M.P. Sir Charles

Forster, ably assisted by the Chairman of the Building

Committee, Alderman Holden, J.P.

A technical day school for boys was opened at the institute

in1891. It had 52 pupils.

|

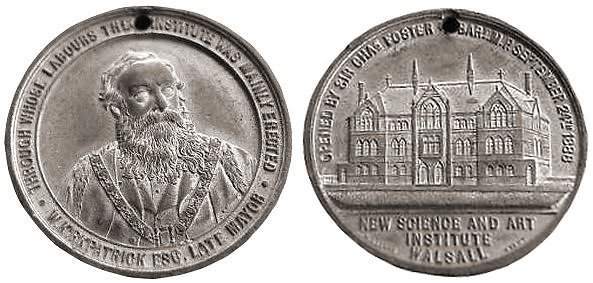

The commemorative medallion,

celebrating the opening of the Science and Art Institute.

From an old postcard.

From an old postcard.

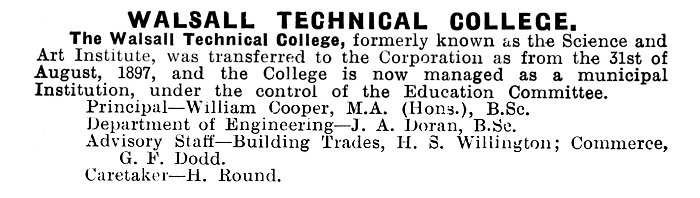

On 31st August, 1897 the institute was transferred

to Walsall Council and became the Walsall Municipal Science

& Art Institute. Eleven years later it moved to Goodall

Street, and in 1926 became Walsall Technical College.

From the 1934 Walsall Red Book.

From the 1899 Walsall Red Book.

From an old postcard.

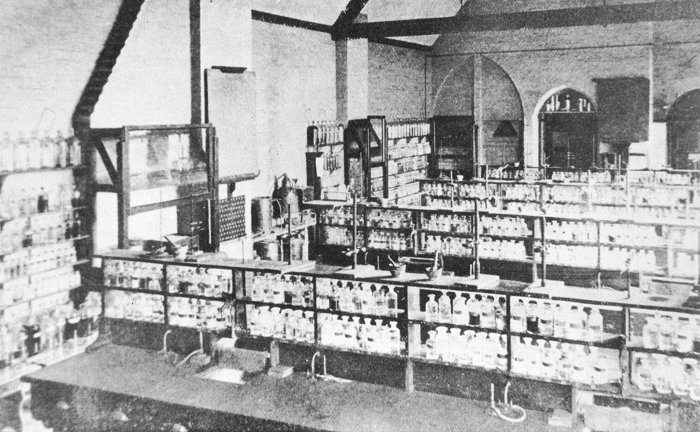

The science laboratory in about

1910.

The Science and Art Institute.

The Science and Art Institute in about

1914.

| |

|

Read about the

Walsall Anarchists |

|

| |

|

|